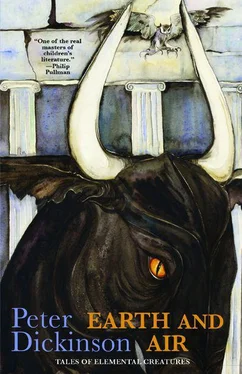

Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Big Mouth House, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth and Air

- Автор:

- Издательство:Big Mouth House

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9781618730398

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth and Air: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth and Air»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth and Air — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth and Air», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But he did, and dreamed. He was following Ridiki along a track at the bottom of an unfamiliar valley, narrow and rocky. She was trotting ahead with the curious prancing gait her bent leg gave her, her whole attitude full of amused interest, ears pricked up and cupped forward, tail waving above her back, as if she expected something new and fascinating to appear round the next corner, some odour she could nose into, some little rustler she could pounce on in a tussock beside the path—pure Ridiki, Ridiki electric with life.

The track turned, climbed steeply. Ridiki danced up it. He scrambled panting after her. The cave seemed to appear out of nowhere. She trotted weightless towards it, while he toiled up, heavier and heavier. At the entrance she paused and looked back at him over her shoulder. He tried to call to her to wait, but no breath would come. She turned away and danced into the dark. When he reached the cave the darkness seemed to begin like a wall at the entrance. He called again and again. Not a whisper of an echo returned. He had to go; he couldn’t remember why.

“I’m coming back,” he told himself. “I’ll make sure I remember the way.”

But as he trudged sick-hearted along the valley everything kept shifting and changing. A twisted tree beside the track was no longer there when he looked back to fix its shape in his mind, and the whole landscape beyond where it should have been was utterly unlike any he had seen before.

At first light the two cocks crowed, as always, in raucous competition. He had grown used to sleeping through the racket almost since he’d first come to live on the farm, but this morning he shot fully awake and lay in the dim light of early dawn knowing he’d never see Ridiki again.

He willed himself not to be seen moping. It was a Saturday, and he had his regular tasks to do. Mucking out the mule shed wasn’t too bad, but there was a haunting absence at his feet as he sat in the doorway cleaning and oiling the harness.

“Sorry about that dog of yours,” said Nikos as he passed. “Nice little beast, spite of that gammy leg, and clever as they come. How old was she, now?”

“Five.”

“Bad luck. Atalanta will be whelping any day now. Have a word with your uncle, shall I?”

I don’t want another dog! I want Ridiki!

He suppressed the scream. It was a kind offer. Nikos was his uncle’s shepherd, and his uncle listened to what he said, which he didn’t with most people.

“They’ll all be spoken for,” he said. “He only let me keep Ridiki because Rania had dropped a skillet on her leg.”

“Born clumsy,” said Nikos. “May be an extra, Steff. Atalanta’s pretty gross. Let’s see.”

“They’ll be spoken for too.”

This was true. The Deniakis dogs were famous far beyond the parish. Steff’s great-grandfather had been in the Free Greek Navy during the war against Hitler, stationed in an English port called Hull, and he’d spent his shore leaves helping on a farm in the hills above the town. There were sheep dogs there who worked to whistled commands, and he’d talked to the shepherd about how they were trained. When the war was over and he’d come to say good-bye the farmer had given him a puppy, which he’d managed to smuggle aboard his ship and home. Once out of the navy he’d successfully trained some of the puppies she’d born to the farm dogs, not to the lip-whistles the Yorkshire shepherds used but to the traditional five-reed pipe of the Greeks.

Now, forty years later, despite the variable shapes and sizes, the colouring had settled down to a yellowish tan with black blotches, and the working instinct stayed strongly in the breed. Steff’s uncle could still sell as many pups as his bitches produced, all named after ancient Greeks, real or imaginary. They were very much working dogs, and Nikos used to train them on to sell ready for their work. But for Rania’s clumsiness Ridiki would have gone that way, as the rest of the litter had.

All day that one moment of the dream—Ridiki vanishing into the dark, as sudden as a lamp going out—stayed like a shadow at the side of his mind. It didn’t change. He had a feeling both of knowing the place and of never having been there before. But if he tried to fix anything outside the single instant, it was like grasping loose sand. The details trickled away before he could look at them.

He fetched his midday meal from the kitchen and ate it in the shade of the fig tree, and then, while the farm settled down to its regular afternoon stillness, went to look for Papa Alexi.

Papa Alexi was Steff’s great-uncle, his grandfather’s brother. Being a younger son he’d had to leave the farm, and look for a life elsewhere. He wasn’t anyone’s father, but people called him Papa because he’d trained as a priest, but he’d stopped doing that to fight in the Resistance, and then in the terrible civil wars that had followed. That was when he’d stopped believing what the priests had been teaching him, so he’d spent all his working life as a schoolmaster in Thessaloniki. He’d never married, but his sister, Aunt Nix, had housekept for him after her own husband had died. When he’d retired they’d both come back to live on the farm, in the old cottage where generations of other returning wanderers had come to end their days in the place where they’d been born.

The farm could afford to house them. There were other farms in the valley, as well as twenty or thirty peasant holdings, but Deniakis was much the largest, with Nikos and three other farmhands, and several women, on the payroll, working a large section of the fertile land along the river, orchards and vineyards, and a great stretch of the rough pasture above them running all the way up to the ridge.

Steff found Papa Alexi as usual under the vine, reading and drowsing and waking to read again. Today Aunt Nix was sitting opposite him with her cat on her lap and her lace-making kit beside her.

“You poor boy,” she said. “I know how it feels. It’s no use anyone saying anything, is it?”

Steff shook his head. He didn’t know how to begin. Papa Alexi marked his page with a vine leaf and closed the book.

“But you wanted something from us all the same?” he said.

“Well . . . are there any caves up in the mountains near here? Big ones, I mean. Not like that one on the way to Crow’s Castle—you can see right to the back of that without going in.”

“Not that I know of,” said Papa Alexi.

“What about Tartaros?” said Aunt Nix. “That’s a really big, deep cave, Steff. It’s on the far side of Sunion.”

“Only it isn’t a cave, it’s an old mine,” said Papa Alexi. “Genuinely old. Alexander the Great paid his phalanxes with good Tartaros silver. There were seams of the pure metal to be mined in those days. You know perfectly well you persuaded me to go and look for silver there once.”

“Only you got cold feet when it came to crossing into Mentathos land. We were actually looking down at the entrance, Steff . . .”

“You wouldn’t have been the one Dad thrashed. Anyway, you knew it was a mine, back then.”

“Of course I did. But that doesn’t mean it can’t have been a perfectly good cave long before it was ever a mine. Nanna Tasoula told me it used to be one of the entrances to the underworld. There was this nymph Zeus had his eye on, only his brother Dis got to her first and made off with her, but before he could get back into the underworld through one of his regular entrances Zeus threw a thunderbolt at him. Only he missed and split the mountain apart and made an opening and Dis escaped down there. That’s why it’s called Tartaros. Nanna Tasoula was full of interesting stories like that, Steff.”

“And you believe in all of them,” said Papa Alexi. “You know quite well it was a mine.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth and Air»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth and Air» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth and Air» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.