Laura Schlitz - The Hero Schliemann

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Laura Schlitz - The Hero Schliemann» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2006, ISBN: 2006, Издательство: Candlewick Press, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hero Schliemann

- Автор:

- Издательство:Candlewick Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2006

- ISBN:978-0-7636-6567-8

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hero Schliemann: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hero Schliemann»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hero Schliemann — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hero Schliemann», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When the articles were published, Heinrich was in trouble, as he fully deserved to be. Though Greece and Turkey had been at odds for hundreds of years, the Greek government agreed that Schliemann ought to return the treasure to the Turks. When the authorities came to claim it, the treasure had vanished again. It seems likely that Heinrich divided it among the members of the Engastromenos family, who hid it in caves and barns.

Heinrich knew that he might go to jail, but didn’t care. “I kept everything valuable that I found for myself and thus saved it for science,” he wrote self-righteously. Guards surrounded the house. Policemen searched his belongings. The Schliemann bank accounts were frozen. Heinrich was questioned about the whereabouts of the treasure, but he kept his mouth shut. Only once did he come close to admitting his guilt. The Turks had arrested Effendi Amin, the watchman who had been hired to keep an eye on the Schliemann excavation. Heinrich felt no shame about stealing the treasure or smuggling it out of the country, but it distressed him that Effendi Amin should be put in jail for what he had done. He wrote to the Turkish government, pointing out that the loss of the treasure was not Amin’s fault — he had done his best. He begged them, “in the name of humanity” to set Amin free.

There was a long court case. Eventually the Turks gave up and agreed that Heinrich should pay them for the treasure, a fine of fifty thousand francs. He joyfully sent five times that amount and a number of artifacts he did not greatly admire. Once again, his luck had held. Perhaps Hermes, the Greek god of thieves, protected him. Against all odds, he was able to keep the Trojan gold.

He was not, however, as celebrated as he had hoped to be. Many scholars felt that more evidence was needed before Hissarlik could be renamed Troy. Others found Heinrich’s theories ridiculous, his stories preposterous. Cartoons and caricatures of the Schliemanns filled the newspapers.

All his life, Heinrich Schliemann was to irritate his colleagues. Though many scholars befriended him, he also made enemies — and his enemies simply could not stand him. They were disgusted by his romanticism, his boasting, his hysterical excitement over every new idea. It rankled that a grocer turned millionaire should unearth such staggering finds. Schliemann was a shrill and vulgar little man. What right had he to come up with theories?

Three years of frustration followed. Though he had gained fame, Heinrich had failed to dazzle the scholarly world, and he could not get permission to mount another excavation — this time at Mycenae. Because Mycenae was known to be a Bronze Age site, Heinrich hoped to find weapons and pottery similar to those he had found at Hissarlik. He also hoped to find the tomb of Agamemnon, the warrior king of The Iliad . Unfortunately, neither the Greek nor the Turkish government had any intention of letting him dig up anything. Who can blame them?

Heinrich argued and coaxed. It did no good. At last he resorted to bribery. He spent a huge sum of money to knock down an ugly tower that blocked a view of the Parthenon. The people of Athens had hated this eyesore for centuries, but no one had ever been willing to pay to get rid of it. Heinrich was willing to foot the bill. Shortly afterward, he received permission to dig at Mycenae. The rules of this firman were strict. Everything he found would belong to Greece — and he was limited to digging inside the city walls.

As it happened, Heinrich wanted to dig within the city walls. He believed that the royal tombs would be found inside Mycenae. He owed this belief to a Greek writer named Pausanias, who visited Mycenae in the second century of the Common Era.

Of course other scholars had read Pausanias, too, but they brought more knowledge to their reading. They knew that the city of Mycenae had once possessed two sets of walls, one inside the other. They reasoned that the space inside the inner wall was too small to hold the tomb of a great king. If royal tombs existed, they were certain they must lie somewhere between the inner and outer walls. It is probable the Greek government gave Schliemann permission to dig within the inner city walls because there was little chance of his finding anything there.

But Heinrich’s hunch turned out to be an auspicious one — he found the tombs. Quite early on, he came upon a circle of stone markers. Inside the circle were tombstones that marked the entrance to narrow tunnels, leading straight down. At the bottom of the tunnels were underground chambers — shaft graves. Pausanias had mentioned five royal tombs, and Heinrich discovered exactly five shaft graves. (There were in fact six, but Heinrich trusted Pausanias completely; after he found the fifth grave, he stopped looking.)

As Heinrich had hoped, the graves were royal tombs, and they were magnificently rich. Fifteen royal corpses were heaped with gold. The men wore gold death masks and breastplates decorated with sunbursts and rosettes. The women were adorned with gold jewelry. All around the bodies were bronze swords and daggers inlaid with gold and silver, drinking cups made of precious stones, boxes of gold and silver and ivory. Once again, Heinrich was half-mad with enthusiasm. “I have found an unparalleled treasure,” he wrote. “All the museums in the world put together do not possess one fifth of it. Unfortunately nothing but the glory is mine.”

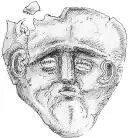

The tombs of Mycenae were even more spectacular than “Priam’s treasure.” The artifacts were exquisite, but that was not all — many of the artifacts matched exactly the descriptions found in Homer’s Iliad . Wine cups, swords, jewels, bracelets, helmets — everything was in keeping with Homer’s Bronze Age world. To crown it all, one of the gold-masked warriors had died in the prime of manhood. This, Heinrich felt certain, was the hero from The Iliad , the murdered Agamemnon. He knelt down and kissed the gold mask. Afterward, according to a famous story, Heinrich telegraphed the king of Greece with the words, “I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon.”

This sounds like the sort of telegram Heinrich might have sent if he had thought of it, but the words are not his. Some other romantic soul invented the tale of the telegram — for once Heinrich himself was not responsible — and it has become part of the colorful Schliemann legend.

Was the dead king Agamemnon? No. Scholars have since determined that the shaft graves date from a hundred to three hundred years before the Trojan War. They were, however, Bronze Age graves. Heinrich was getting closer to the Homeric world he sought, but it still eluded him.

When a triumphant Heinrich published his findings about Mycenae, he revealed a lost world. The Bronze Age, that shadowy period between 1600 and 1100 BCE, had been drawn into the spotlight. The glory of that spotlight cast a golden glow over Heinrich Schliemann. He became a celebrity.

For the second time in his career, Heinrich’s finds gave rise to scholarly debate. Many scholars felt that none of the shaft graves was ancient enough to be the resting place of the legendary king. One critic even thought that the “mask of Agamemnon” was meant to be an image of Jesus Christ. Heinrich grew testy when scholars refused to accept his bearded warrior as Agamemnon. “All right,” he snapped, “let’s call him Schultze!” From that moment on, the warrior king was referred to as “Schultze.” Schultze’s mask continues to puzzle archaeologists up to the present day. It is unique in design, and some scholars consider it a forgery.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hero Schliemann»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hero Schliemann» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hero Schliemann» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.