Laura Schlitz - The Hero Schliemann

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Laura Schlitz - The Hero Schliemann» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2006, ISBN: 2006, Издательство: Candlewick Press, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hero Schliemann

- Автор:

- Издательство:Candlewick Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2006

- ISBN:978-0-7636-6567-8

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hero Schliemann: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hero Schliemann»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hero Schliemann — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hero Schliemann», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

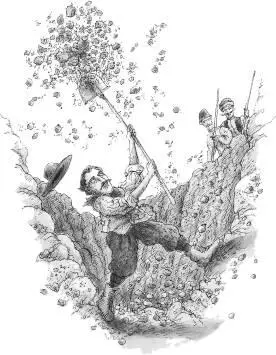

The thrust of his plan was to dig — deep. At the top of the mound, he expected to find a Roman city, then a Greek city underneath, then a Greek city from the time of Homer, and, just below that, the walled city of The Iliad . Instead of carefully sifting through the mound, layer by layer, he decided to dig out vast trenches — rather as if he were removing slices from a cake. Since Homer’s Troy was ancient, Heinrich expected to find it near the bottom.

And so he dug, violently and impatiently. Frank Calvert advised him to proceed with care, to sift through what he was throwing away, but Heinrich was not a cautious man. He whacked away at the mound as if it were a piñata.

Modern archaeologists do not dig like this. They remove the earth gently and keep detailed records of what they find. If they find an artifact that isn’t what they’re hoping to find, they don’t discard the artifact: they change their ideas. Instead of looking for something, they examine whatever comes to light. Heinrich, of course, was looking for Homer’s Troy. “Troy . . . was sacked twice,” modern archaeologists remark, “once by the Greeks and once by Heinrich Schliemann.” It is generally agreed that Schliemann did more damage than the Greeks.

His early finds were not very interesting. He discovered the remains of a wall. He found coins, a few bones, the clay whorls that women used in spinning thread. Later there were little objects made of clay, which he thought were “owl-headed” vases, sacred to Athena. He was looking for weapons like the “pitiless bronze” spears described by Homer — but the weapons he found were made of stone. Heinrich was bewildered. He was seeking the remains of a great city. Where was the bronze armor, the palaces and jewels?

Spring turned to summer. The climate of Hissarlik tends to extremes — bitter cold in winter, blistering heat in summer, and a wind that never stops blowing. Since Homer sang of “windy Troy,” Heinrich had once rejoiced that Hissarlik was windy, but his enthusiasm for high winds was waning. Gusts of air blew grit into his eyes. Dust scratched his skin and filled his mouth when he tried to speak.

As the workmen dug, they unearthed thousands of poisonous snakes. Hissarlik was also home to scorpions and mosquitoes. At night, it was difficult to sleep: there were so many shrieking owls and croaking frogs. Poisonous centipedes invaded the Schliemann bed.

The workmen grew weary of hauling heavy wheelbarrows full of earth. They began to work more slowly, frequently pausing to smoke. Heinrich badgered them about their smoking. He believed that smoking wasted time and weakened the body.

Heinrich had become an unpaid doctor. He hated dirt and disease, and could not see either without wanting to meddle. He gave the workers quinine in order to prevent malaria. He preached the virtues of exercise, fresh fruit, and sea bathing.

Heinrich was particularly proud of curing a girl of seventeen. She was almost too weak to walk, she coughed uncontrollably, and her body was covered with ulcers. Heinrich was shocked by her frailty and the filthy rags she wore. He called for castor oil and administered a dose; he also asked Sophia to give the girl a pretty dress from her own wardrobe. He taught his patient a few simple exercises and told her to take daily sea baths. A month later, she walked three miles to kiss the dusty shoes of “Dr. Schliemann.” Her cough was gone, and the ulcers were healed. She was happy and strong.

Heinrich was touched by her gratitude, but — as he often complained — he had come to Hissarlik to excavate Troy, not to play doctor. He urged the workers to dig deeper, to go faster.

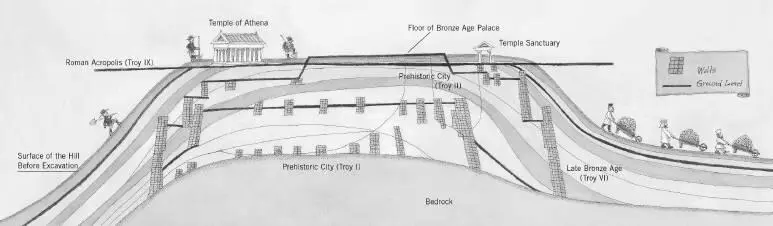

The first season ended. Heinrich hired more workmen. He was beginning to understand the way the mound was layered. Little by little, he came to distinguish between the ruins of four different cities — cities that lay on top and outside of another, like nesting dolls or the layers of an onion.

In an onion, however, the layers are orderly. At Hissarlik, the layers are uneven and the boundaries overlap. The site would have confounded a far more experienced archaeologist than Heinrich Schliemann. “It was an entirely new world for me,” confessed Heinrich. “I had to learn everything by myself.”

When Heinrich Schliemann dug at Hissarlik, he was hoping to find Homer’s city of Troy. Instead, he found many cities, one on top of the other. Sorting out the different layers, or strata, was a difficult job .

In order to understand Heinrich’s work, imagine that you’ve tossed everything that you’ve ever owned into a heap in the middle of the floor. On top of the mound would be the clothes you wore yesterday. Lower down, the clothes would be smaller. Legos and puzzle pieces would get bigger. At the bottom of the mound would be baby clothes, board books, and rattles .

If you looked at the mound like an archaeologist, you’d see all the layers of your past life. You would keep a sharp eye out for anything that might help you to assign dates to the different strata. If, for example, you found your second-grade report card next to a plastic stegosaurus, you might guess that second grade was the year you were crazy about dinosaurs .

Now suppose your mother wanted to give away the red boots you loved when you were four. Suppose she tore apart your mound like a dog looking for a bone. What had once been an orderly mess would become chaos. The original layering, which made sense, would be lost forever .

What Heinrich Schliemann did at Hissarlik was quite a bit like that .

During the second season, Heinrich found a panel of carved marble that showed the sun god in his chariot. Though the panel, which dates from between 355 and 281 BCE, was not old enough to belong to Homer’s Troy, it was the largest and most beautiful object yet found — and it was found on Frank Calvert’s land. Calvert and Schliemann had agreed that whatever was found on Calvert’s section of the mound would be divided between them, but the marble panel could not be cut in half. Heinrich wanted the whole thing. He offered to pay Frank Calvert for his share of the sculpture.

It was the end of their friendship. Since their first meeting, Frank Calvert had been unstinting with his knowledge and advice. Now Heinrich haggled like the cut-throat businessman he was. He succeeded in beating down the price, but he lost Calvert’s respect. Later, when Calvert published criticisms of Schliemann’s theories in historical journals, Schliemann felt betrayed.

Heinrich was publishing his discoveries almost as quickly as he made them. He expected the scholars of the world to applaud his labor; instead they accused him of jumping to conclusions. Heinrich raged at the criticism but continued to dig, assisted by his wife. At night the Schliemanns stayed up late, measuring, sketching, and recording their finds. Sophia, who had been so homesick in the grand hotels of Europe, accepted the primitive living conditions without a murmur, though she wore four pairs of gloves during the winter.

As Heinrich continued to study the mound, he came to believe that the second city from the bottom was the city of Homer’s Iliad . It was a prehistoric city, with a paved ramp, a magnificent tower, and a huge gate, which Heinrich at once assumed was the “Scaean Gate” of The Iliad . The walls had been skillfully constructed, and — even more important — showed signs that the city had once been burned, like Homer’s Troy.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hero Schliemann»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hero Schliemann» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hero Schliemann» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.