Laura Schlitz - The Hero Schliemann

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Laura Schlitz - The Hero Schliemann» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2006, ISBN: 2006, Издательство: Candlewick Press, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hero Schliemann

- Автор:

- Издательство:Candlewick Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2006

- ISBN:978-0-7636-6567-8

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hero Schliemann: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hero Schliemann»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hero Schliemann — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hero Schliemann», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Heinrich was by no means the first to consider Hissarlik as a possible site for Troy. For the last hundred years, there had been scholars who suspected that Troy was at Hissarlik rather than Bunarbashi. One of these men was an archaeologist named Frank Calvert. It was Frank Calvert who first discovered that what looked like a large hill on the Turkish plain was actually a mound made by human beings. Frank Calvert believed that inside that mound lay the lost city of Troy. He bought some of the land and started digging. When Heinrich met Frank Calvert in 1868, he adopted Calvert’s beliefs: “I completely shared Frank Calvert’s conviction that the plateau of Hissarlik marks the site of ancient Troy.”

Throughout this book, dates are given in terms of the Common Era. The “Common Era” is a new way of talking about historic dates. American and European historians have traditionally used a calendar based on Christianity. Events of ancient history — like the Trojan War — were given a “BC” after the number, meaning, “before Christ.” Things that happened after the birth of Christ were labeled “AD” for “anno Domine” — Latin words for — in the year of Our Lord.”

Common Era dating uses the same numbers, but different initials after the dates. What used to be called 5 BC (five years before Christ) is now called 5 BCE (five years before the Common Era.) Historians use Common Era dates as a way of being courteous to people of all religions. Common Era dates are also more accurate, since it is not certain exactly when Jesus Christ lived .

Heinrich gave Hissarlik the same “tests” he had administered at Bunarbashi. He concluded that Hector and Achilles could easily have run the nine miles around this mound. He was delighted to discover a ruined temple, a nearby swamp, and a mountain range in the distance — all of which reminded him of landscapes in The Illiad . “The beautiful hill of Hissarlik grips one with astonishment,” he wrote later. “That hill seems to be destined by nature to carry a great city.” All of the clues in The Iliad seemed now to point to Hissarlik as the site of ancient Troy. Heinrich was so excited that he ordered a chicken dinner to celebrate. Unfortunately, the chicken who was to be the main course objected to the whole idea and ran for its life, squawking in panic. Heinrich, who had a soft spot for animals, paid the owner to set the chicken free and sat down to a poultry-free supper in high good humor.

Heinrich Schliemann is famous for “finding Troy.” Many people give him credit for being the first to look for Troy in the right place — but by right, that honor belongs to Frank Calvert. If Heinrich Schliemann had not met Frank Calvert on his journey, he might never have excavated at Hissarlik. The admission “I . . . shared Frank Calvert’s opinion” changed gradually to “Frank Calvert, the famous archaeologist . . . shares my opinion. . . .” Eventually Heinrich, who admitted that he was “a braggart and a bluffer,” made the discovery sound as if it were his alone.

Frank Calvert, however, was a remarkably generous man. He must have realized that Heinrich had the energy, as well as the money, to organize a large-scale excavation. He gave Heinrich the benefit of his archaeological knowledge and explained how to get permission to dig from the Turkish government. Heinrich promised to return to Hissarlik the following year, permission in hand.

The years 1868 and 1869 were remarkable ones in Heinrich’s life. He retired from business, appointed himself Homer’s champion, and divorced his wife.

He began to dream of a Greek bride: dark-haired, interested in Homer, and — if possible — beautiful. He had no desire for a rich bride. He knew he was not handsome, and he hoped to make up for it with a well-padded wallet and a knowledge of foreign languages. He told his Greek tutor, Theokletos Vimpos, that he wanted his future wife to love learning “because otherwise she cannot love and respect me.” Above all, he wished for “a good and loving heart.”

As it happened, Theokletos had an unmarried niece: dark-haired, bookish, and poor. Sophia Engastromenos was only sixteen years old when her photograph was sent to the forty-seven-year-old millionaire. Her youth frightened Heinrich. He was afraid that so young a girl would have her heart set on romance. But Sophia’s photograph enchanted him, and at last he declared that he had fallen in love.

Having fallen in love with Sophia, it only remained to meet her. The Engastromenos family was excited by the prospect of having a millionaire in the family, and Sophia was bundled into her sister’s best dress. When Heinrich spoke to her alone, he asked her point-blank, “Why do you wish to marry me?” Sophia replied, “Because my parents have told me that you are a rich man!”

Heinrich flew into a temper and marched back to his hotel room to sulk. The Engastromenos family huddled around Sophia, begging her to send a letter of apology. Sophia wrote that she had not meant to offend her suitor; she had answered honestly because she believed that he wanted the truth.

Heinrich forgave her. By this time, he was head over heels in love. For the second time in his life, he married a woman he had barely met, a woman whose family was in need of money. This time, his wife was thirty years younger than himself — Sophia was so young that she smuggled her dolls along on her honeymoon.

Poor Sophia! During the first months of married life, Heinrich dragged her to museums all over Europe. She preferred the circus. He lavished expensive gifts upon her, supervised her diet, and drew up a gymnastics program that he thought would keep her healthy. He pestered her to learn foreign languages. She suffered from headaches, stomachaches, and homesickness.

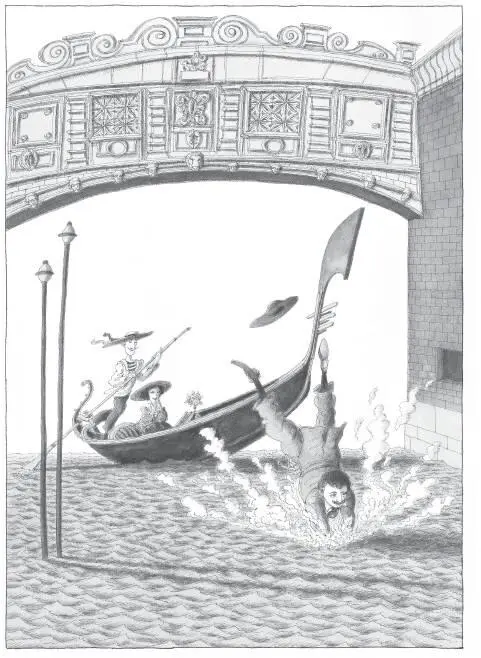

And yet the marriage was not a disaster. Sophia Schliemann was loving and wise beyond her years. She relieved Heinrich’s deep loneliness. She made up her mind that “Henry” was a genius and that geniuses were not quite like other people. She even awakened a streak of playfulness in his nature — on their honeymoon in Venice, he dived headfirst out of a gondola in order to make her laugh. She called him her “friend for life” and “dearest husband.”

As for “Henry,” his love and respect for Sophia increased as he came to know her better. To him, she was his “adored wife and everlasting friend.” He admired her mind as well as her beauty and concluded, “I knew I loved and needed a woman of her grandeur.”

In 1871, Sophia gave birth to a baby girl who was christened Andromache, after the Trojan princess in The Iliad . Shortly after Andromache’s birth, Heinrich received the firman , or permission, he had been seeking from the Turkish government. The terms of the agreement were simple: Heinrich was responsible for all expenses. If artifacts were found, half of them were to be given to the new museum in Constantinople. A supervisor was appointed to keep a watchful eye on the amateur archaeologist. Heinrich disliked the man and grumbled over having to pay his salary.

When Heinrich began digging at Hissarlik, he had very little idea what he was doing. He knew that he wanted to dig into the mound and find a city of the Bronze Age, but he didn’t know what a Bronze Age city would look like. His guide was Homer — he was looking for artifacts and architecture that matched the descriptions in Homer’s poetry. This was not a scientific approach.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hero Schliemann»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hero Schliemann» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hero Schliemann» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.