Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

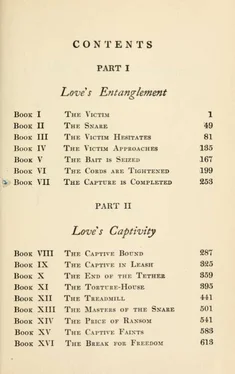

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"No, I am not insane, I tell myself; I am not insane! It is the circumstances of my life that cause this melancholia and misery. It has been my life, from the very beginning—for what a hopeful and joyous creature I would have been, had I only had a chance as a girl! I know that; and you must tell it to me, and help me to believe it."

Thyrsis read this with less surprise than Corydon had imagined; for she had been wont to drop hints about her trouble from time to time. He was shocked, however, to find what a hold it had taken upon her; the thing sent a chill of fear to his heart. Could it be after all that she had some taint? But he saw at once that he must not let her see any such feeling; the least hint of it would have driven her to distraction. On the contrary, he must minimize the trouble, must help her to laugh it away, as she asked.

He went to meet her in the park, and found her in an agony of distress; she had mailed the letter, and then she had wished to recall it, and had been struggling

ever since with the idea that he would be disgusted with her. Now, when she found that such was not the case, that he still loved her and trusted her, she was transported with gratitude.

"But dearest," he said, "how absurd it is to be ashamed of an idea! If ugly things exist, don't we have to hear of them and know of them? And so why frighten ourselves because they are in our minds ?"

"But Thyrsis," cried she, "they are so hateful!"

"Yes," he said. "But then the more you hate them, the more they haunt you!"

"That's just it!" she exclaimed.

"But what harm can they do? Can they have any effect upon your character? You must say to yourself that all this is a consequence of the structure of your brain-cells. What could be more futile than trying to forget? As if the very essence of the trying was not remembering!"

So Thyrsis went on to argue with her. He made her promise him that in future she would tell him of all her obsessions, permitting no fear or shame to deter her; and so thereafter he would have to listen periodically to long accounts of her psychological agonies, and help her to hunt out the "hob-goblins" from the tangled thickets of her mind. They were forever settling the matter, positively and finally—but alas, only to have something uniettle it again. So Thyrsis had to add to his other accomplishments the equipment of a psycho-pathologist; he brushed up his French, and read learned treatises upon the researches in the Sal-petriere, and the theories of the "Nancy School".

§ 4. ANOTHER month passed by, and still there was no rift in the clouds. Once more Corydon was for-

bidden to see him, and so her pain grew day by day. At last there came another letter, voicing utter desperation. Something must be done, she declared, she was slowly going out of her mind. Thyrsis could have no idea of the shamefulness of her position, the humiliations she had to face. "I tell you the thing is putting a brand upon my soul," she wrote. "It is something I shall never get over all my life. It is withering me up—it is destroying my self-respect, my very decency; it is depriving me of my power to act, or even to think. People come in, relatives or friends—even strangers to me—and peer at me and pry into my affairs; I hear them whispering in the parlor—'Hasn't he got a position yet?' or 'How can she have anything to do with him?' The servants gossip about me—the woman I have for a nurse despises me and insults me, and I have not the courage to rebuke her. To-day I went almost wild with fury—I rushed into the bathroom and locked the door and flung myself upon the floor. I found myself gnawing at the rug in my rage—I mean that literally. That is what life has left for me!

"I tell you you must take me away, we must get out of this fiendish city. Let us go into the wilderness as you said, and live as we can—I would rather starve to death than face these things. Let us get into the country, Thyrsis. You can work as a farm-hand, and earn a few dollars a week—surely that could not be a greater strain upon us than the way things are now."

When Thyrsis received this, he racked his brains once more; and then he sat down and wrote a letter to Barry Creston. He told how he had worked over the play, and how it had gone to ruin; he told of his present plight. He knew, he said, that Mr. Creston had been interested in the play, and that he was a man

who understood the needs of the artist-life. Would he lend two hundred dollars, which would suffice until Thyrsis could get another work completed?

He waited a week for a reply to this; and when it arrived he opened it with trembling fingers. He half expected a check to fall fluttering to the floor; but alas, there was not a single flutter. "I have read your letter," wrote the young prince, "and I have considered the matter carefully. I would do what you ask, were it not for my conviction that it would not be a good thing for you. It seems to me the testimony of all experience, that artists do their great work under the spur of necessity. I do not believe that real art can ever be subsidized. It is for men that you are writing; and you must find out how to make men hear you. You may not thank me for this now, but some day you will, I believe."

After duly pondering which communication, Thyrsis racked his wits, and bethought him of yet another person to try. He sat himself down and addressed Mr. Robertson Jones. He explained that he was in this cruel plight, owing to his having devoted so many months to "The Genius." Even the actors had received something for the performances of the play they had given; but the author had received nothing at all. He asked Mr. Jones for a personal loan to help him in a great emergency ; and he promised to repay it at the earliest possible moment. To which Mr. Jones made this reply— "Inasmuch as the failure of the play was due solely to your own obstinacy, it seems to me that your present experiences are affording exactly the discipline you need."

§ 5. HOWEVER, there are many ups and downs in

the trade of free-lance writer. The very day after he had received this letter, there came, in quick succession, two bursts of sunlight through the clouds of Thyrsis' despair. The first was a letter, written in a quaint script, from a man who explained that he was interested in a "Free People's Theatre" in one of the cities of Germany. "You will please to accept my congratulations," he wrote; "I had never known such a play as yours in America to be written. I should greatly be pleased to translate the play, so that it might be known in Germany. Our compensation would have to be little, as you will understand; but of appreciation I think you may receive much in the Fatherland."

To which Thyrsis sent a cordial response, saying that he would be glad of any remuneration, and enclosing a copy of the manuscript of "The Genius". And then— only two days later—came the other event, a still more notable one; a letter from the publisher who had been number thirty-seven on the list of "The Hearer of Truth". Thyrsis had got so discouraged about this work that he now sent it about as a matter of routine, and without thinking of it at all. Great, therefore, was his amazement when he opened the letter and read that this publisher was disposed to undertake it, and would be glad to see him and talk over terms.

Thyrsis went, speculating on the way as to what strange manner of being this publisher might be. The solution of the mystery he found was that the publisher was new at the business, and had entrusted his "literary department" to a very young man who had enthusiasms. The young man held his position for only a month or two; but in that month or two Thyrsis got in his "innings".

The publisher wished to bring the book out that

spring. He offered a ten per cent, royalty, and the trembling author summoned the courage to ask for one hundred dollars advance; when he got it, he was divided between his delight, and a sneaking regret that he had not tried for a hundred and fifty!

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.