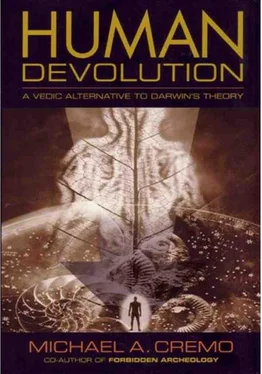

Michael Cremo - Human Devolution - A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Cremo - Human Devolution - A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Torchlight Publishing, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Human Devolution: A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory

- Автор:

- Издательство:Torchlight Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:9780892133345

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Human Devolution: A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Human Devolution: A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Human Devolution: A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Human Devolution: A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The souls of persons who committed suicide and persons who have been murdered go directly to Miyvo. Others must make a journey that can last several days (Hawes 1903, p. 163). After a person dies, there is a ceremonial preparation for the journey. Hawes witnessed such a ceremony for a recently deceased woman. The body was kept in a hut for four days. During this time, the woman’s soul was visiting the four principle gods of the Gilyak with the purpose of giving an account of her life and receiving instructions for the afterlife. Her relatives kept her company, remembering and reciting her good deeds and qualities. Because the god of fire serves as a channel of communication to the other gods, a fire is kept burning constantly in the hut. The body of a dead person is dressed in new garments and provided with the best nets, spears, rifles, and bows for the journey to Miyvo (Shternberg 1933, p. 80). The dead person receives a new name, and according to Shternberg (1933, p. 368), the Gilyak consider it a sin to call the dead person by the person’s old name.

Cosmology of the Incas

The main god of the Incas of South America was called Viracocha. Rowe (1946, p. 293) said that Viracocha was “the theoretical source of all divine power, but the Indians believed that He had turned over the administration of his creation to a multitude of assistant supernatural beings, whose influence on human affairs was consequently more immediate.” Viracocha dwells in the celestial region, but descends to the terrestrial region, appearing to humans in times of crisis. This is similar to the Vedic concept of the avatar, “one who descends.” In the Bhagavad Gita (4.7) , the Supreme Lord Krishna says, “Whenever and wherever there is a decline in religious practice and a predominant rise in irrelgion, at that time I descend myself.” After he created the earth, Viracocha wandered through it, exhibiting miracles and giving instruction to the people. After reaching the place called Manta, in Ecuador, he set off to the West, walking on the waters of the Pacific Ocean (Rowe 1946, p. 293).

There was a golden idol of Viracocha, the supreme creator, in the main temple in Cuzco, capital of the Inca empire. It was of manlike form, but about the size of a boy of ten years (Rowe 1946, p. 293). Temples for worship of Viracocha were established throughout the Inca empire, along with farming fields to provide income for servants and sacrificial performances (de Molina 1873, p. 11).

One prominent early historian, Garcilaso de la Vega (1539–1616), identified Viracocha with another supreme creator called Pachacamac. Garcilaso de la Vega was the son of an Inca princess and a Spanish conquistador, and therefore his knowledge of Inca religion was acquired from an Inca perspective. Pacha means universal and camac, according to Garcilaso de la Vega (1869–1871, p. 106), is “the present participle of the verb cama, to animate, whence is derived the word cama, the soul.” Thus Pachacamac means “He who gives animation to the universe”, or, more accurately, “He who does to the universe what the soul does to the body” (Garcilaso de la Vega 1869–1871, p. 106). This corresponds to the Vedic concept of Supersoul, which exists in several forms. One form of the Supersoul resides within the body of each living entity, along with the individual soul. Another manifestation of the Supersoul animates the entire universe.

The name of God, Pachacamac, was held in great reverence, and the Incas never uttered it without special gestures such as bowing, or raising the eyes to heaven, or raising the hands. Garcilaso de la Vega (1869–1871, p. 107) says, “When the Indians were asked who Pachacamac was, they replied that he it was who gave life to the universe, and supported it; but that they knew him not, for they had never seen him, and that for this reason they did not build temples to him, nor offer him sacrifices. But that they worshipped him in their hearts (that is mentally), and considered him to be an unknown God.” But there was one temple to Pachacamac in a coastal valley of the same name. Garcilaso de la Vega (1869–1871, p.

552) says, “This temple of Pachacamac was very grand, both as regards the edifice itself and the services that were performed in it. It was the only temple to the Supreme Being throughout the whole of Peru.”

According to some historians, the Incas originally worshiped the sun as supreme. But one of the early Inca rulers noted that the sun was always moving, without any rest. It could also be seen that even a small cloud could cover the sun. For these reasons he concluded that the sun could not be the supreme god.Therefore, there must be a higher being who controlled and ordered the sun. This ultimate supreme being he called Pachacamac (de Molina 1873, p. 11).

After Virococha (or Pachacamac), the god next in importance in the Inca system of worship was the sun god, the chief of the sky gods. Inca royalty were accepted as the children of the sun, and were taken to be divine beings themselves (Garcilaso de la Vega 1869–1871, p. 102). The first Inca queen was called Mama Uaco. She was a beautiful woman and also a sorceress. She could speak with demons, and she also empowered sacred stones and idols ( huacas ) to speak. She was the daughter of the sun and moon. Somehow, with no earthly husband, she had a son, the Mango Capac Inca, whom she married, taking a dowry from her father, the sun god. The later Inca kings were descended from her. The sun god presided over the growing of crops, and thus his worship was very important among the primarily agricultural Inca people. There was an idol of the sun in the main Inca temple in Cuzco (Rowe 1946, p. 293).

Next in importance was the moon goddess. She was called MamaKilya, “Mother Moon.” She was the wife and sister of the sun. Her movements guided calculations of time and determined the calendar of Inca festivals (Rowe 1946, p. 295). The Thunder God was the god of weather. The Incas prayed to him for rain. His form was that of a man in the sky, holding in one hand a war club and in the other a sling. Thunder was produced by the loud crack of his sling, and lightning was the flash of his shining garments. In producing rain, he took water from the Milky Way, a heavenly river, and poured it down on the earth. He was called by the names Ilyap’a, Intil-ilyap’a, or Coqu-ilya, and was identified with a constellation similarly named (Rowe 1946, pp. 294–295).

The stars were regarded as the handmaidens of the moon (Garcilaso de la Vega 1869–1871, p. 115). Among the stars, the Incas worshiped the Pleiades, which they called Collca. Certain stars presided over different earthly affairs, and were specifically worshiped for this reason. For example, shepherds worshiped the star Lyra, which they called Vrcuchillay. They considered this star to be a many-colored llama, with powers to protect livestock (Polo de Ondegardo 1916, pp. 3–4). Incas in the mountains worshiped the star Chuquichinchay, which means moutain lion. It was in charge of lions, jaguars, and bears, from which the Incas desired protection. This star is part of the constellation Leo. The Incas worshiped the star Machacuay, which ruled over snakes. According to Polo de Ondegardo (1916, p. 5), Machacuay represented the crab, corresponding to a star in the constellation Cancer. Other stars represented the divine mother (Virgo), the deer (Capricorn), and rain (Aquarius).

The earth was called Pacha Mama (Earth Mother), and the sea was called Mama Qoca (Mother Sea). They were worshiped as supernatural goddesses (Rowe 1946, p. 295). The Inca people also paid homage to many local gods, down to the level of household deities. They worshiped plants, trees, hills, and stones, such as the emerald. They also worshiped animals such as jaguars, mountain lions, foxes, monkeys, great snakes, and condors (de la Vega 1869–1871, p. 47).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Human Devolution: A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Human Devolution: A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Human Devolution: A Vedic Alternative To Darwin's Theory» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.