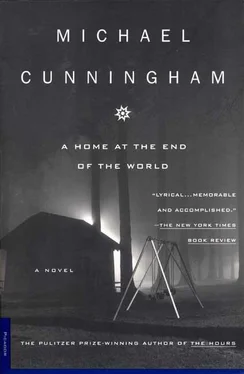

Michael Cunningham

A HOME AT THE END OF THE WORLD

This book is for Ken Corbett

The Poem That Took the Place of a Mountain

There it was, word for word,

The poem that took the place of a mountain.

He breathed in its oxygen,

Even when the book lay turned in the dust of his table.

It reminded him how he had needed

A place to go to in his own direction,

How he had recomposed the pines,

Shifted the rocks and picked his way among clouds,

For the outlook that would be right,

Where he would be complete in an unexplained completion:

The exact rock where his inexactnesses

Would discover, at last, the view toward which they had edged,

Where he could lie and, gazing down at the sea,

Recognize his unique and solitary home.

—WALLACE STEVENS

ONCE our father bought a convertible. Don’t ask me. I was five. He bought it and drove it home as casually as he’d bring a gallon of rocky road. Picture our mother’s surprise. She kept rubber bands on the doorknobs. She washed old plastic bags and hung them on the line to dry, a string of thrifty tame jellyfish floating in the sun. Imagine her scrubbing the cheese smell out of a plastic bag on its third or fourth go-round when our father pulls up in a Chevy convertible, used but nevertheless—a moving metal landscape, chrome bumpers and what looks like acres of molded silver car-flesh. He saw it parked downtown with a For Sale sign and decided to be the kind of man who buys a car on a whim. We can see as he pulls up that the manic joy has started to fade for him. The car is already an embarrassment. He cruises into the driveway with a frozen smile that matches the Chevy’s grille.

Of course the car has to go. Our mother never sets foot. My older brother Carlton and I get taken for one drive. Carlton is ecstatic. I am skeptical. If our father would buy a car on a street corner, what else might he do? Who does this make him?

He takes us to the country. Roadside stands overflow with apples. Pumpkins shed their light on farmhouse lawns. Carlton, wild with excitement, stands up on the front seat and has to be pulled back down. I help. Our father grabs Carlton’s beaded cowboy belt on one side and I on the other. I enjoy this. I feel useful, helping to pull Carlton down.

We pass a big farm. Its outbuildings are anchored on a sea of swaying wheat, its white clapboard is molten in the late, hazy light. All three of us, even Carlton, keep quiet as we pass. There is something familiar about this place. Cows graze, autumn trees cast their long shade. I tell myself we are farmers, and also somehow rich enough to drive a convertible. The world is gaudy with possibilities. When I ride in a car at night, I believe the moon is following me.

“We’re home,” I shout as we pass the farm. I don’t know what I am saying. It’s the combined effects of wind and speed on my brain. But neither Carlton nor our father questions me. We pass through a living silence. I am certain at that moment that we share the same dream. I look up to see that the moon, white and socketed in a gas-blue sky, is in fact following us. It isn’t long before Carlton is standing up again, screaming into the rush of air, and our father and I are pulling him down, back into the sanctuary of that big car.

WE GATHERED at dusk on the darkening green. I was five. The air smelled of newly cut grass, and the sand traps were luminous. My father carried me on his shoulders. I was both pilot and captive of his enormity. My bare legs thrilled to the sandpaper of his cheeks, and I held on to his ears, great soft shells that buzzed minutely with hair.

My mother’s red lipstick and fingernails looked black in the dusk. She was pregnant, just beginning to show, and the crowd parted for her. We made our small camp on the second fairway, with two folding aluminum chairs. Multitudes had turned out for the celebration. Smoke from their portable barbecues sharpened the air. I settled myself on my father’s lap, and was given a sip of beer. My mother sat fanning herself with the Sunday funnies. Mosquitoes circled above us in the violet ether.

That Fourth of July the city of Cleveland had hired two famous Mexican brothers to set off fireworks over the municipal golf course. These brothers put on shows all over the world, at state and religious affairs. They came from deep in Mexico, where bread was baked in the shape of skulls and virgins, and fireworks were considered to be man’s highest form of artistic expression.

The show started before the first star announced itself. It began unspectacularly. The brothers were playing their audience, throwing out some easy ones: standard double and triple blossomings, spiral rockets, colored sprays that left drab orchids of colored smoke. Ordinary stuff. Then, following a pause, they began in earnest. A rocket shot straight up, pulling a thread of silver light in its wake, and at the top of its arc it bloomed purple, a blazing five-pronged lily, each petal of which burst out with a blossom of its own. The crowd cooed its appreciation. My father cupped my belly with one enormous brown hand, and asked if I was enjoying the show. I nodded. Below his throat, an outcropping of dark blond hairs struggled to escape through the collar of his madras shirt.

More of the lilies exploded, red yellow and mauve, their silver stems lingering beneath them. Then came the snakes, hissing orange fire, a dozen at a time, great lolloping curves that met, intertwined, and diverged, sizzling all the while. They were followed by huge soundless snowflakes, crystalline bodies of purest white, and those by a constellation in the shape of Miss Liberty, with blue eyes and ruby lips. Thousands gasped and applauded. I remember my father’s throat, speckled with dried blood, the stubbly skin loosely covering a huge knobbed mechanism that swallowed beer. When I whimpered at the occasional loud bang, or at a scattering of colored embers that seemed to be dropping directly onto our heads, he assured me we had nothing to fear. I could feel the rumble of his voice in my stomach and my legs. His lean arms, each lazily bisected by a single vein, held me firmly in place.

I want to talk about my father’s beauty. I know it’s not a usual subject for a man—when we talk about our fathers we are far more likely to tell tales of courage or titanic rage, even of tenderness. But I want to talk about my father’s frank, unadulterated beauty: the potent symmetry of his arms, blond and lithely muscled as if they’d been carved of raw ash; the easy, measured grace of his stride. He was a compact, physically dignified man; a dark-eyed theater owner quietly in love with the movies. My mother suffered headaches and fits of irony, but my father was always cheerful, always on his way somewhere, always certain that things would turn out all right.

When my father was away at work my mother and I were alone together. She invented indoor games for us to play, or enlisted my help in baking cookies. She disliked going out, especially in winter, because the cold gave her headaches. She was a New Orleans girl, small-boned and precise in her movements. She had married young. Sometimes she prevailed upon me to sit by the window with her, looking at the street, waiting for a moment when the frozen landscape might resolve itself into something ordinary she could trust as placidly as did the solid, rollicking Ohio mothers who piloted enormous cars loaded with groceries, babies, elderly relations. Station wagons rumbled down our street like decorated tanks celebrating victory in foreign wars.

Читать дальше