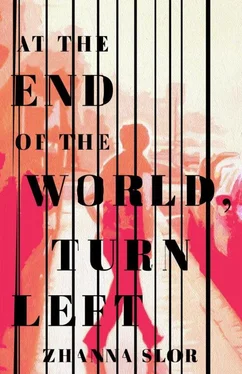

Zhanna Slor

AT THE END OF THE WORLD,

TURN LEFT

Dedicated to the memory of my mother, Edit Vaynberg, and my grandparents, Nikolai and Khaya Vaynberg.

MASHA

________________

CHAPTER ONE

The second I land in Milwaukee, I’m a different person. My whole body tenses, from my leather-booted feet to my long brown hair, crimped into stifled curls during the fourteen-hour flight from Israel. If my dad notices any of this, he doesn’t mention it. He’s smoking again, staring out the window. I haven’t seen him with a cigarette in years, and for a second I can’t help but wonder if I got in the right car. But there is no mistaking his dusty, maroon clunker in which I spent much of the nineties dreaming of other continents. Nor is my unsmiling Russian father difficult to distinguish from the other middle-aged men idling at the arrivals terminal.

“Hey,” I say, sinking into the old sun-bleached passenger seat. I decide not to ask about the Marlboro Lights on the dash next to a Nirvana sticker I’d once pasted there, nor why the right mirror is still duct-taped on at a strange angle, like a misplaced limb. When it comes to my dad, it’s better to wait until he offers information. Normally this drives me crazy, but I’m too tired to feel much of anything. I attempt a smile anyhow. “I appreciate your efforts to save money for my inheritance, but you might want to consider getting a car that’s not held together by superglue?”

Papa starts driving onto the highway, Mitchell Airport a giant brown slab in the rearview mirror, along with my regular life; schwarma, Nescafé, sirens and underground bunkers. David’s faded Golani t-shirt coiled around his tanned biceps, his gun never too far from his body, or mine. I suddenly miss it in a way I hadn’t noticed throughout my hastily planned flight. Gone is my semi-upbeat disposition, buoyed by three mini-bottles of wine and an endless stream of movies I’d watched on the plane. In its place a familiar, unsettling discomfort takes root.

Papa, more at home in this discomfort than not, is still mulling over my failed attempt at levity.

“If it ain’t broke…” he finally replies, in a thick Russian accent that makes me momentarily homesick before finding its way into the humorous part of my brain.

I find myself stifling a laugh. “Papa, I don’t think you understand that saying.”

“Right. I just stupid old man.”

“But it is broke…” I start. “Forget it.” I don’t bother trying to explain.

My dad’s hands are so tight on the wheel it pains me to look at him. Maybe coming back was a bad idea. I generally try to avoid lending credence to his anxieties, which have always hung over us like humid air that never draws rain. I try to tell him: everyone’s healthy, everyone’s safe. Isn’t that something? But in his mind, it’s still 1980s Soviet Ukraine. No matter how much money we had growing up, it was never enough; no matter how safe, it was not safe enough. This is how we ended up in the middle of Wisconsin, the only Russian kids for hundreds of miles, not to mention the only Jews. Well, that, and my great-aunt Rachel happened to live in Wisconsin, and since she sponsored us to immigrate, we had to come here too. That didn’t mean we had to stay .

“Papa!”

“What?”

I grab his phone out of his hand, stopping him from typing instead of looking at the road. I catch what I think is an email header from a law firm. Without looking at it again, I put the tiny machine into the cupholder with two fingers, as if touching it will spread some disease I don’t want.

“People crash from doing this every second of the day,” I explain. It’s the first iPhone I’ve seen in real life, and something about it gives me the chills. Or maybe I’ve been spending too much time among the Israeli Orthodox.

“Maria Pavlova.” My dad rolls his eyes, his use of my full name and patronymic inducing a slight cringe. No one ever calls me anything but Masha. “Forty years I driving.”

“That was before Steve Jobs,” I explain. I cover his phone with my hand so he can’t retrieve it. No way I’m going to die on Highway 43 surrounded by dried-out empty fields and fireworks warehouses. “These things are dangerous. Trust me, in twenty years they’ll call it a plague.”

“Plague,” my dad laughs. “Bozhe moy, you sound like your sister. It’s 2008, Maria. Soon cars drive themselves. If you don’t use all tools at disposal—”

“Then you’re always going to be at a disadvantage, I know,” I finish. “The thing you always forget is that tools can also be weapons.”

“Oh, I don’t forget.” He shakes his head and lights another cigarette, his expression dark again. Watching him chain-smoke like that, I feel myself get worried for the first time since he called. Or maybe it’s the familiarity of the drab Wisconsin roads, all that flat, dry land, punctuated only by strip malls and convenience stores. The sight of it produces an agitated feeling in my gut. Only then does it occur to me I could have said no to coming back. But my dad had been so riled up—it was Yom Kippur so, like most of Israel, our phones had been turned off for almost two days by the time he got through to me—that I’d automatically agreed to everything he said. There’s a German adjective for this, fisselig, which means flustered to the point of incompetence as a result of another person’s direction. If our phone call—admittedly, our entire relationship—could be summed up by one word, it would probably be that one.

That isn’t entirely why I said yes—I said yes because my dad has never directly asked me to come home, not once. He is not the kind of person to request favors. It was a sign, him asking me to do this on Yom Kippur, the day of atonement. Even I couldn’t ignore a sign so obvious. I’d done the unthinkable, in a Russian immigrant family: not only did I avoid becoming a doctor, lawyer, or engineer, I’d dropped out of college. And left the country on top of it. The country they had chosen . I can’t explain exactly why, but once my eyes saw the landscape of Israel—its ancient, dazzling architecture sprinkled across endless hills, the overly friendly young parents and bustling cafés sprouting up on pieces of land so old it’s impossible to fathom—it was inevitable. I was, to put it simply, meant to live in Israel. As immigrants themselves, you’d think my parents would understand this, but it had proved to be the opposite, if anything.

I turn to face Papa. “So. What’s the plan?” I ask. Downtown flies past us, a measly constellation of skyscrapers split down the middle by the snake of the Milwaukee River.

“Huh?” he asks, his forehead lined with confusion.

“What do you mean, huh ?” I ask, louder, equally confused. Papa blows out a cloud of smoke through the crack of the window, the rush of air making it suddenly loud. I can’t get over how weird it is to see him smoke again. Like I’ve jumped through a time portal and I’m suddenly twelve, not twenty-five. Any minute now, I’ll sprout acne and gain ten pounds of water weight. “You made me come all the way out here, and you have no plan?”

My dad inhales again before he speaks, his words coming out smoky. “What are you saying? Is that Hebrew?”

“Oh! Sorry. I didn’t even notice,” I sputter, switching back to English. I could probably go with Russian, but I am too jetlagged to attempt untangling the wild mess of grammar that my native language calls for. If we’d come from the Soviet Union a little later, say when I was thirteen as opposed to nine, I would probably have a native’s perfect grasp of Russian. But my parents were really into the whole American Dream thing when I was growing up, and our Russian skills suffered as a result. They didn’t know that by the time we could attain it, the American Dream had morphed into something else entirely, and no one could pinpoint what it was anymore. Maybe that was the whole point. In America, the dream is whatever you think it is.

Читать дальше