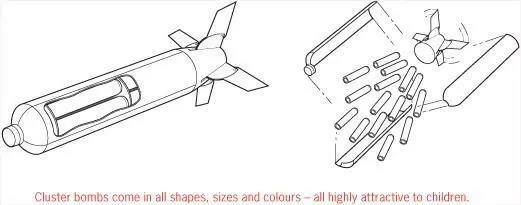

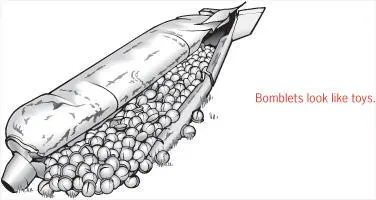

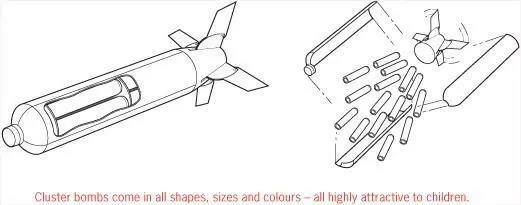

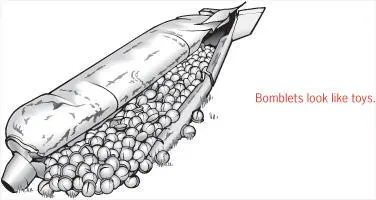

Cluster munitions are also a prevalent menace. These are air-dropped or artillery-fired weapons that disburse hundreds of smaller submunitions over an area. They are usually designed to detonate on impact with the ground. Each cluster weapon can carry up to 2000 small bomblets, but they have a failure rate of up to 10 per cent, so can leave a sizeable and explosive contamination problem for years to come.

Even just a short time after a conflict, cluster munitions that scattered but did not detonate can become buried under sand or vegetation. No longer visible, they can have a similar impact to landmines that have been deliberately planted. Countries such as Laos have an enormous number of unexploded bomblets littering the countryside. More recent conflicts in Lebanon, Gaza, Iraq and Afghanistan are all characterized by cluster-bomb contamination.

Never be tempted to touch anything or pick up ‘souvenirs’ from a battle area. In the summer of 2003 Hiroki Gomi, a Japanese reporter working in Iraq, picked up an unexpended cluster munition without realizing what it was. He packed it in his bag to take home as a souvenir from the war. While it was going through the X-ray scanner at Amman airport in Jordan, the cluster munition exploded, killing the security guard making the inspection.

If you find yourself close on the heels of conflict or in the conflict itself, there may be a temptation to take souvenirs, or to poke around in abandoned buildings and military emplacements. Do not do this. You could well activate unstable UXO, or trigger a booby trap (see Improvised Explosive Devices) designed specifically to attract your attention.

Taking souvenir photographs of people sitting on tanks or other destroyed military equipment may also expose you to depleted uranium (DU). Shells made from the extremely dense material DU, which is used to destroy armour, might vaporize on impact, contaminating the surrounding area with radioactive dust particles that could be absorbed into the body through inhalation, for example. Unnecessary exposure to toxic DU can lead to long-term health effects.

Landmineshave been a favourite tool of warring parties precisely because they are easy to deploy while being difficult to detect and remove. Most countries that experience conflict will have a legacy, great or small, of mine warfare. Landmines can stay active almost indefinitely, just as potent and deadly as the day they were laid, or perhaps even more so as triggering mechanisms might have frayed or decomposed.

Anti-personnel (AP) minesare designed to kill or maim individuals. Warring parties prefer the latter as the care and treatment of victims will absorb manpower that would otherwise have been used for operations.

Anti-tank minesare specifically designed to destroy or disable vehicles or armour, not individual personnel. The most common form of activation for mines is by pressure (from a foot or car tyre). However, tripwires and other forms of activation – proximity sensors, tilt-switches, magnetic attraction, and specifically designed anti-handling systems – can be used too.

There is a common myth that there is a delay between activating a landmine and it exploding: the reality is that the explosion is instantaneous.

Landmines and booby traps can be found anywhere that conflict has occurred. They can, for example, be laid as a ‘nuisance’ for advancing forces in houses, gun placements, trenches, rest-stops by the side of the road or at water sources. They can also be laid in patterned arrangements in clearly identified locations.

Nick Toksvig recalls a frightening experience during the Kosovo War: ‘We were in a village and found the mayor’s house, which had been abandoned. There was a path leading to the front door, but I chose to make my way across the lawn. I knew it was an official’s house and had probably been booby-trapped as the Serbs retreated, but I didn’t really pay enough attention to that. At one point a colleague told me to stand very still. A couple of centimetres from my heel was a small landmine that, had I stepped on it, would have taken off at least my leg. We had no security with us, and I had certainly advanced without the necessary caution.’

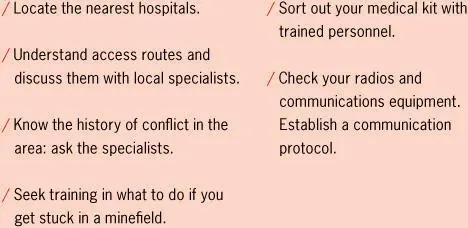

Understanding the mine threat in a particular area or location requires an understanding of the conflict that has taken place there, preferably learnt from witnesses (civilian or military). It’s also important to have some knowledge of mine-related incidents or accidents that have occurred. It is standard practice for UN agencies, host governments, specialist NGOs and commercial companies to collect this data in a systematic way.

If you are embedded with military forces, they will provide you with their own guidelines for safe conduct. However, the level of acceptable risk for military personnel is higher than that usually tolerated by civilians during either conflict or peacetime. If you are not working with the military but will be operating in an area that has or might have experienced conflict, you should contact the local UN or governmental Mine Action Centre (MAC), or an agency that you know is concerned with demining or mine action. Mine action is the provision of an integrated set of services designed to reduce the impact of landmines and UXO working to a commonly accepted set of international standards.

BEFORE HEADING INTO A MINED AREA…

Remember that understanding of the mine threat can change as better information becomes available. Make sure always to check the latest information when planning field missions. If there is an area that you know or suspect to be mined, avoid it – do not even go near it.

A minefield will often look indistinguishable from any other piece of land. However, there may be telltale signs.

• Locals might be avoiding the area, despite its obvious use for agriculture or for transport access.

• Dead animals might be seen in the area.

• Waxed packaging used to store the mines may be littering the ground.

• The area may be overgrown.

• Locals or organizations might have tried to mark out the area of the minefield using sticks, stones or more formal markings (see opposite). Always be conscious of your surroundings.

Signs of mines

There are dozens of different signs used to mark mined areas. They go far beyond the more traditional skull and crossbones. Mary O’Shea reports that: ‘In Sudan the minefields are apparently marked by red Coca-Cola cans. I am unsure if Pepsi and Diet Coke have any significance.’

Some of the more formal signs are illustrated below.

/IF YOU FIND YOURSELF IN A MINEFIELD…

Remember the following mnemonic – MINED – from The UN Landmine and UXO Safety Handbook .

Movement stops immediately. Remain still and do not move your feet. If you are in a vehicle, do not try to reverse through your tracks. Do not move the steering wheel. Stay inside the vehicle. Keep calm.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)