My colleague Jane Dutton, who lives in South Africa, told me: ‘My dad lent me a small handgun after a family friend was shot and another friend of ours was broken into, but I gave it back after a week. I knew it would get used if I found someone breaking into my house. I was angry and scared enough. But nine times out of 10 the criminal will end up using your handgun against you. I didn’t want that risk.’

Warning:If you use a weapon in a war zone, it can change your legal status to ‘mercenary’ under the Geneva Convention (see Medics) – not a particularly good idea if you are captured.

Chris Cobb-Smith, who has contributed to earlier parts of this book, is my security expert. I asked him for advice on the subject of guns, and for a few basic instructions on how to work a weapon if you really need to use one.

Few subjects cause as much controversy as that of firearms. However, it is unavoidable, an ever-present fact of life, and encountered continually in the high-risk regions so much in the news today.

For some, carrying a firearm is as natural as carrying a mobile phone, almost a natural extension of the arm – a comforting and continually present friend. For others they are objects of bewilderment and revulsion: ‘Why on earth would I want a gun?’ Whatever stand you take, some rudimentary knowledge is necessary, and here is some advice:

Never touch a firearm unless you are totally confident in its operation.But if you have to, avoid any contact with the trigger as some are extremely sensitive.

Always keep the barrel pointing away from people.Direct it up in the air or, if the ground is soft, downwards.

Remember, firearms can be ‘attractive’ items and in some scenarios could be booby-trapped, so again, do not touch them unless it’s imperative to do so.

Should you ultimately be driven to use a gun in a life or death situation, try to remain calm and take the following steps:

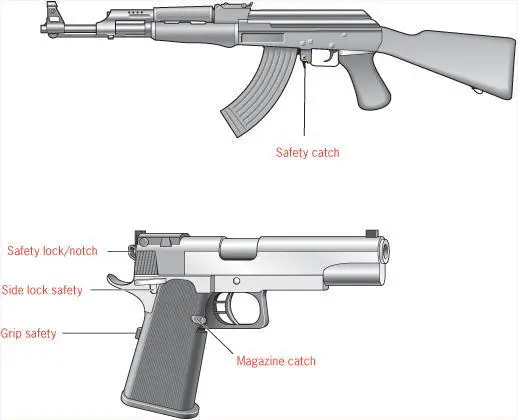

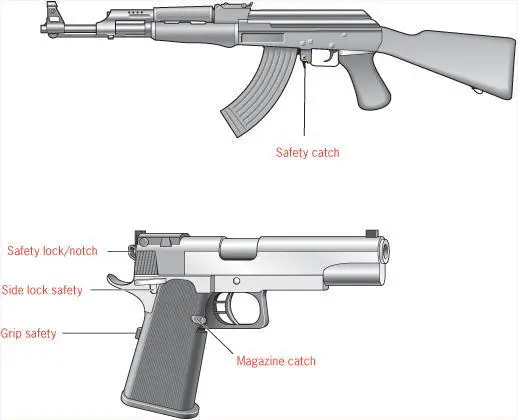

Look for the safety catch – internationally, ‘S’ stands for ‘Safe’.

Choose a setting – ‘R’ for ‘Repeat’ and ‘A’ for ‘Automatic’. For accuracy and control, select ‘R’, allow the weapon to point naturally, aim at the centre of mass of your target and squeeze (don’t pull) the trigger.

My advice is that if you feel the need to be armed, you should leave the weapons in the hands of experts like Chris. But the process of finding the right kind of security is a delicate one. Do you go local or do you outsource? It depends on the task at hand.

Let’s start with a few observations about Western ‘security contractors’. I don’t mean to generalize – and goodness me, have I seen my share of handsome bodyguards – but all too often ‘security’ means a bunch of pasty, tattooed, slightly overweight men who have arrived in a country for the first time with few or no local contacts. They tend to charge a fortune to tell you that you can’t do what you need to do in order to keep your job. However highly trained and excellent they are, they stick out like a sore thumb, and so will you.

Shadi Alkasim advises: ‘Avoid hiring a muscly bodyguard: it could draw attention to you and might lead to you getting kidnapped or killed. People might attack you, believing that you are working as a spy with the forces of the armies stationed there. Or they could hijack you for a ransom demand in the belief that you are someone important and rich, and you could end up dead.’

But if you are heading into an unknown area or disaster zone, the bodyguard’s knowledge, experience and ability to adapt to any situation is invaluable. What they don’t know when they turn up they make it their job to learn. There is a network that spans the world, and they will tap into it for the best local knowledge.

Film-maker James Brabazon told me: ‘In Liberia I employed a South African ex-mercenary as a bodyguard – the only time I have used an expat as an armed guard. He was dressed in a military uniform and carried a gun, which is an entirely different thing from a journalist carrying a gun. If he had been arrested, he would have been tried as a mercenary and probably shot. They wouldn’t have done that to me. He understood that.’

James has made it his business to mix in worlds where most people wouldn’t dare to go. Even the ballsiest people I know look at work by James and wonder why he decided to put himself at such risk. The first film I saw of his was a documentary made in Liberia during the war there in 2003. While filming with the rebels, a notoriously nasty bunch, James got to know them and understand their impulses. After that he was chosen as the official documenter of the failed coup in Equatorial Guinea. His book and film about the man behind that coup, Simon Mann, is called My Friend the Mercenary . James says good security is not just about finding the right man for the job – it’s about learning to listen to him too:

‘In Liberia in 2002 I was filming rebel soldiers fighting against government troops at close range. I wanted to stay in the position where I was filming from, but a rebel commander wanted me to move back. It had taken me about two hours to get there crawling on my hands and knees under fire. I was very reluctant to move back. The South African mercenary I had hired to protect me, Nick du Toit, insisted I move back. I still said no, but he grabbed me and dragged me to one side. An RPG [rocket-propelled grenade] hit the spot where I had been standing. The group of people I had been standing with were all killed or injured. Deafened by the blast, we were shouting at each other, trying to work out what to do next. Our noses were two or three inches apart and a bullet passed between us. He grabbed me again and we ran back into cover. My advice is this: if you have employed someone because of their expertise and value them for it, listen to them – even if it is inconvenient.’

On the other hand – and here I risk a sweeping generalization – foreign security guards tend to err on the side of caution. You have to learn when to listen to them and when to follow your own instincts. Nick Toksvig agrees:

‘There had been a terrible bombing at Qurna, in Lebanon. It was the second by the Israelis in a number of years. It was highly contentious and the Israelis were on high alert. Rumour said that they were targeting cars going along the road from Beirut to the south. Our security guy told us not to go. I listened to him, but I also knew we were in the country to cover stories exactly like this. I decided we should risk it. We got there and they were still pulling children’s bodies out of the rubble. It was awful.’

If you can find good local security guards, you are onto a winner. Look for discipline and, if they are in a team, a clear hierarchy. You need to be able to communicate clearly with them. They need to be clear on your objectives, what you need to do each day, but you also have to trust that they will know when to say no. At other times you might need to push them for a little more caution because the land and people are so familiar to them. Take time to get to know them and even their families if you can. They could be risking their life for you. Their partnership with you will be noted by the local community. They will be judged one way or another long after you have moved onto the next job.

According to Nick Toksvig, local hire can be a hit and miss affair: ‘We drove from Peshawar through the Khyber Pass into Jallalabad in November 2001. The hunt for Bin Laden was under way and we were making our way to Tora Bora. We travelled by convoy and hired local armed guards throughout the time we were there. They were OK, but it’s always a risk hiring someone carrying a gun. Their loyalty is to the money rather than you. If someone pays them more, they can stab you in the back.’

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)