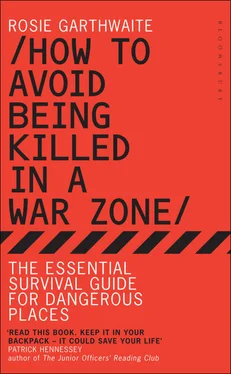

Patrick Hennessey

7/ Feeding Yourself Under Fire

You can eat anything… When I was teaching Royal Marines what they could eat in extremis, I would buy maggots from a fishing tackle shop, add some beetroot and they would turn pink, like prawns. The class would gobble them up quite happily, and only felt squeamish when I told them afterwards what they had eaten. The lesson is: don’t die or get sick for the sake of being fussy. Food is fuel. It is amazing what people can survive on.

Dr Carl Hallam

Surviving on a dietof monotonous food is hell for me. Faced with limited options – say, falafel seasoned with sand every evening for four months, or ‘Menu F’ army ration box for 21 days, or Baghdad hotel spaghetti bolognese for a month’s worth of lunch and dinners – I often choose not to eat at all after a while. I get lazy and I get hungry.

But tell me that there is no food for the next three days and I will transform into an über-efficient hunter-gatherer, a jungle chef par excellence, whose sole mission is to present anyone within plate-pushing distance with gourmet grubs, boiled potato scraps, strangled hen or whatever I can get my hands on.

I discovered I had these abilities while on a tour through the rainforests of northern Bolivia. We were 10 hours’ boat-chug away from the nearest town when we heard that the river had been blocked off by a local strike. We were supposed to return that day, but we decided to stay in camp and wait for it to end as these strikes can get violent.

When the drinking water grew dangerously low and the petrol for powering the boat almost ran out, our wise guide decided we needed to take control of our own welfare. He began to delegate tasks amongst us plump, dirty-looking Westerners. We didn’t know where our strengths would lie. I was chosen to be the piranha-catcher, but it wasn’t meant to be. Six hours hunched over our dugout canoe and I had managed to get through all the bait – potential food for the evening – and failed to catch anything at all.

The trick with piranhas is speed. They will always go for the bait, but if you hesitate for a second, they will bite off the hook with their tiny, sharp teeth before you can reel them in. I’m sure there are many ways to catch them, but our guide told us to keep the line short – around half a metre long – and tied to one finger. The moment you feel even the slightest tug, you simply flick your finger up, bringing the greedy fish and hook to a bounce on the boat floor.

I had lost three hooks by the time I conceded defeat and handed over to my vegetarian friend Kathy. With her extraordinary patience and future doctor’s digits, she began to pluck piranhas from the water with all the ease and rhythm of a metronome.

One group returned to camp with grins as wide as their captured snake was long, while another group was covered in cuts and bruises sustained in bringing home a huge juicy palm heart. I made fire, boiled water and listened to their tales of how man took on nature and won. That night we feasted. But hunting and gathering is exhausting work. Relentless too. People grew bored with the long treks to find dangerous beasties, and the even longer ones dragging back palms through the mosquito- and leech-infested jungle. By the time a passing boat told us that the strikers were willing to let us through, we were hungry and tired of the adventure. We wanted a can of baked beans and a cold beer. We headed home, most of us having used our penknives properly for the first and last time.

We had been in a fertile area where, despite our difficulties, it was relatively easy to find food. Outside the jungle, of course, food is cheap and very easy to come by in most parts of the world. That makes it even harder for most of us to cope when that quick bite to eat is snatched away.

Laura McNaught remembers getting by on a very limited diet in the Congo: ‘You can survive on beer and bananas for longer than you might think – in my case, three days. In fact, anything deep-fried or fruit with skin should be OK, especially if it’s washed down with some bug-killing alcohol. Boiled eggs and a Dioralyte [rehydration powder] are a good breakfast option, and you can never pack too many cereal bars.’

This book is not about extreme survival. It is about survival in unfamiliar and difficult surroundings. Survival against the odds, but mainly against man rather than nature. And when nature wins – in an earthquake, flood or tsunami – you need to be prepared (see Basic Survival). In this chapter I am largely assuming you are not intending to be too far from local people and therefore some kind of food. But I have included some basics about hunting, gathering, fishing and fire, which should keep you going if, for instance, your car breaks down in the middle of nowhere and your original plans are thrown out the window.

Danger and war don’t have to mean deprivation, particularly if you are on the ‘winning’ side. In fact, if you are on an embed with the US military, you will probably get fat on their rations. Back at their base, where you can choose from one of multiple fast-food outlets, you will begin to wonder why you ever had a craving for a Big Mac with double cheese and curly fries.

Each culture you meet will have its own extremes. I have been living in the Arab world for the last few years, so I know the people there adore sugar, especially in their tea and coffee – enough to stand a spoon up in your cup in some cases. In my humble experience, Iraqis have the sweetest tooth. When it comes to food choices, I recommend playing to your host nation’s strengths. The sticky pastries, the delicious pistachio ice cream, the cardamom coffee… These can fire your engine for hours every day. The people really know what they’re doing. And this food is safe. If you push for the less familiar, that is when you are going to get into trouble. For example, opting for sushi on Lake Titicaca can land you in Lima with a drip in your arm after 15 painful hours on a bus to get there. I’ve seen it. But go for ceviche, the local version of sushi, and you will probably be fine. The most important thing to know about the food you are eating in out-of-the-way places is whether it is safe… because you are a long way from a hospital.

For some that means excluding foods their guts don’t trust. Kamal Hyder told me: ‘I am quite fussy about food. I’ve been in situations when a goat has been alive one minute and is served up to you on a plate 15 minutes later. I don’t trust it. I make excuses, say I am too sick to eat meat. I always carry a tin or two of Cheddar and some olives. You can always find warm Afghan bread, warm tea. Stuff like that is always safe. But be careful with water… it can kill.’

My best advice is to stick to what the locals are eating. Ask around and learn what you can and can’t eat. Gather knowledge rather than trying to gather your own food. It will serve you well when there is no one around to help.

Also, work with your surroundings. If you are in Outer Mongolia and you are not a fan of fermented yak’s milk, you need to find a way of politely saying no. If you are a vegetarian and a village kills their last goat in celebration of your arrival, it is going to be tough to find a way out.

Samantha Bolton told me: ‘I gave up being vegetarian after two weeks of boiled and roasted goat and no vegetables in the refugee camps in Tanzania. There’s no point in being precious about diet. It’s a waste of time. Just eat what you are given.’ Leith Mushtaq, however, has a different approach: ‘Normally, I am vegetarian, so I always take a supply of tinned food. I don’t eat meat for politeness’ sake. I pretend I am sick.’

Having worked and travelled with a few vegetarians and fussy eaters, I implore you, do not bother to explain your moral reasoning for saying no. Just do as Leith does and pretend to be ill. It is a lot less painful, and it works… although they may then rustle up a special local potion to make you better instead.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)