Luckily, open demonstrations of anti-Semitism appear to be a marginal problem in the Czech Republic (although a psychologist, Petr Bakalář, experienced a commercial success when he published in 2003 a book where racist views were masked as a scientific report), propably because the country’s repulsive skinheads have so far focused their aggression towards members of the Romaminority. The only slightly controversial issue is a lingering debate about the Jews’ influence on Czech culture.

While some intellectuals, such as the playwright Pavel Kohout, claim that modern Czech culture is a product of three mixed elements — the Slavonic Czech, the German-Bohemian and the Jewish (see: Kafka, Franz), several Czech politicians, most notably President Václav Klaus, maintain that multiculturalism is an empty and meaningless term.

Except for beerand ex-president Václav Havel, there is probably nothing a foreignerassociates more strongly with Prague and subsequently also the Czech Republic than the writer Franz Kafka. Thousands of touristswalk about in the Czech capital dressed in T-shirts with Kafka’s portrait on their chests, they sip coffee in the Franz Kafka Café or visit the English-speaking Franz Kafka Theatre. Some of them have even read one of the novels this modern tourist attraction wrote.

The strange thing, though, is that the Czech Republic officially behaved for a long time as if this literary genius didn’t have any relation to Prague and the country at all. Just to take one example: almost 10 years passed after the Velvet Revolutionuntil Prague’s magistrate managed to name a square after the famous artist. But rather symptomatically, “Franz Kafka Square” is in reality a paved passage so nondescript and anonymous that most cabbies don’t have the faintest idea where it is located (at the corner of Kaprova and Maiselova streets).

This treatment may seem rather ungenerous. If one also takes Kafka’s deep, personal relation to the city into account, it seems almost incomprehensible. Ernst Pawel, one of Kafka’s most renowned biographers, puts it like this: “There is one all-important and fundamental fact in Kafka’s existence: that he was born in Prague, was buried in Prague, and spent nearly all the 41 years of his life in this citadel of lost causes.”

To be precise, he was born in 1883 in a house situated at the very border between the Jewishghetto and Old Town. Bar a short stay in Berlin and a year in the countryside spent with his sister Ottla in Northern Bohemia, Kafka never left Prague, where he gradually occupied 10 different flats. A small house in the Golden Lane at Hradčany and two rented rooms in the Schönborn Palace (now the US Embassy) at the Malá Strana were the farthest he came from Old Town. When he died prematurely at a tuberculosis sanatorium outside Vienna in 1924, he was living in a flat in the Oppelt House at Old Town Square number 6.

“Prague is like a little mother with claws,” Kafka himself summed up his love-hate relations to the city, whose dominant Hradčany Castle most probably served as the physical model for his novel Das Schloss , published in 1926. Another famous location, the stone quarry from Der Prozess (1925) to which Josef K. was led by his anonymous capturers and subsequently executed, was at Kafka’s time situated directly to the west of Hradčany. One might even imagine that the sober bureaucrat Josef K. on his way to work passed Jaroslav Hašek’s brilliant idiot Švejk on his way to his favourite hospoda The Chalice.

Although born into a Jewish and German-speaking family, Kafka came into close contact with his Czech surroundings early on through the family’s maid, and the writer’s father, Herrmann the ambitious merchant, even regarded Czech as his first language. Franz, on the contrary, was educated in Prague’s German schools, so there can be no doubts about his mother tongue, but Czech languagewas an obligatory subject both in grammar school and at the lyceum, and a few Czech-written letters that have been preserved document that he had a very good and lively grasp of colloquial Czech (“... the wind is constantly blowing in our a**es”).

Kafka’s amicable relations with his Slavonic compatriots were clearly demonstrated in 1918, when Czechoslovakia emerged from the ruins of the Austro- HungarianEmpire. While the German management of the Workmen’s Accident Insurance Company, where he was employed for most of his life, was fired and replaced by Czechs, Kafka — now a Czechoslovak citizen — was asked to stay and later promoted. Even his surname, although written as it is pronounced in German, is as Czech as it gets ( Kavka is the Slavonic term for jackdaw).

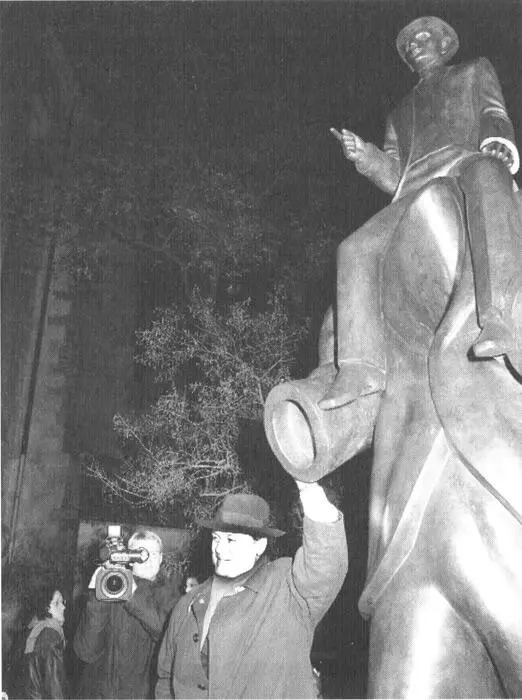

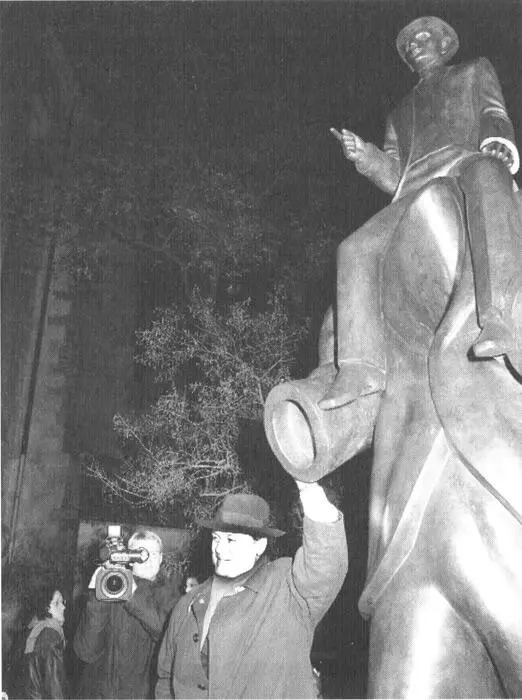

Photo © Jaroslav Fišer

Nevertheless, the Czechs have never come to perceive Franz Kafka as “their man” for two reasons, one national and one political. Combined, they have caused widespread ignorance about the great writer.

The national explanation is rather obvious. Whereas Kafka’s Jewish origin is no hindrance to being considered a “Czech writer” (there are lots of them — starting with Karel Poláček and ending with Ota Pavel), his mother tongue definitely was. As a member of the German-speaking minority that lived in Prague in the interwar years, he could, at best, be regarded as a representative of Bohemia’s multicultural heritage.

However, after the Jews were murdered in Holocaust, the Germans were kicked out of the country in 1945 and the Slovaks— following the separation of Czechoslovakia in 1993 — finally achieved national independence, the Czechs became masters of an ethnically and culturally homogenous state for the first time in centuries. This atmosphere didn’t exactly offer a superabundance of interest and tolerance towards the country’s multicultural heritage.

Neither is the political reason for disregarding Kafka a mystery. As a prophet of existentialism, describing in details how an inhuman and all-mighty society manipulates the powerless individual, Kafka was seen by the Nazis (unfortunately, correctly) as envisaging the terrible bloodshed soon to be released, and his works were prohibited in Germany in 1933.

Not surprisingly, the Czechoslovak communists, who came to power in 1948 (see: Communism), took a similar stance, adding that Kafka was “too pessimistic and decadent” as a writer. Only in 1963, a semi-official literary conference in Liblice north of Prague carefully aired the possibility of making Franz Kafka accessible for Czech readers. Those attempts were mercilessly crushed five years later by Soviet tanks.

Forty years of a publishing ban under the communists and 10 years of ostentatious official ignorance after the Velvet Revolution have taken its toll on Kafka. Today, even fewer Czechs than all those silly tourists with Kafka t-shirts have actually read any of his novels. Ironically enough, the single most palpable trace the shy writer has left is the frequently-used Czech term kafkárna — something Kafkaesque.

Yet there are some bright signs of change. In mid-2003, the inexhaustible people behind the Franz Kafka Publishing House managed to complete the translation of all his works into Czech. Some months later, a no less important event took place, when a full-sized statue of Kafka was finally unveiled in Prague. Located on the border between Old Town and the former Jewish Ghetto, the statue is not only a very belated tribute to Kafka, but also a strong, symbolic acknowledgement of Prague’s multicultural heritage. Since Prague’s mayor personally unveiled the statue, it may even seem that this view at last is being acknowledged officially.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)