Thus, Prague, and in a wider context Bohemiaand Moravia, were rightfully acknowledged as one of the Ashkenazi diaspora’s major cultural centres in Europe.

The Jews’ history in what’s now the Czech Republic began almost 1,000 years ago. Actually, one of the oldest documents about Prague that is preserved was written by the Jewish merchant Abraham ben Jakob, who travelled from Spain to Bohemia sometime around 966. “The city named Fraga is built of stone, and it is the largest trading place in the whole region,” ben Jakob wrote to attract his compatriots.

Some years after ben Jakob’s visit, a Jewish settlement (which in the mid-1200s turned into a regular ghetto behind walls) was established in the Old Town’s northern part, right at the Vltava’s bend. In the following centuries similar settlements-cum-ghettos popped up nearly all over Bohemia and Moravia. Still, more than 150 Jewish cemeteries, many of them devastated by a half century of neglect, and numerous dilapidated synagogues that are slowly being reconstructed (the Bolsheviks, with their usual sensitivity, let local collective farms use some of them as warehouses) give solid evidence of the Jews’ millennium-long presence in cities and towns throughout this country.

As it has everywhere else in Europe, also the Czech Ashkenazi diaspora has witnessed times of both prosperity and persecution.

In the ghettos, the Jews had self-government, but since they were regarded as “direct subjects” of the king, he was allowed in practice to do what he wanted with them. Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612), for instance, constantly pressed the wealthy Jewish banker Mordechai Maizel to lend him money, which the emperor never returned. Maizel, however, discreetly used the debt to make life easier for his fellow believers, among them Rabbi Löw, the famous Talmudist who, according to the legend, created the clay robot Golem.

Twice, in 1541 and 1744, the entire Jewish population was expelled from Bohemia and Moravia, and they also suffered cruel pogroms, although they were fewer than the wild pogroms that frequently hit the Jews in the Russianczardom.

Life changed for the better in the 1790s, when the “enlightened” Emperor Josef II introduced a set of progressive reforms (that’s why Prague’s ghetto is called Josefov ). Jews were allowed to move outside the ghettos, they were ordered to send their children to public schools and also allowed to take a surnameand have a family. During the next century, the Czech Ashkenazi diaspora made a huge step towards emancipation. When the Austro- HungarianEmpire fell apart in October 1918, most of the 120,000 Jews who were living in Bohemia and Moravia easily reconciled with the fact that they had now become citizens of the Czechoslovak Republic.

The First Republicis commonly remembered as a period when the Czech Jewish community flourished. Although reality was probably less rosy, at least for the majority who spoke Germanand not Czech, Masaryk’sCzechoslovakia indubitably offered its Jewish citizens a more liberal atmosphere than Horthy’s Hungary, where Jews faced restricted admission to universities, or Catholic Poland, where anti-Semitism was rife. The Italian novelist Claudio Magris has a telling comparison that illustrates the Czech Jews’ strong assimilation. On the day when Nazi troops marched into Austria after the Anschluss in 1938, several hundred of Vienna’s Jews committed suicide in pure despair. In Czechoslovakia at that time, few Jews believed that their state would fail to protect them.

They were, unfortunately, wrong. Starting in October 1941, Czech citizens of Jewish origin were rounded up and transported to extermination camps in Poland. Many Bohemian Jews, especially children, were first sent to Terezín (Theresienstadt), about 60 kilometres north of Prague. Here, the Nazis turned the former garrison city into a “model” concentration camp, complete with its own orchestra and theatre, which was cynically presented in their propaganda. But ultimately, not even the Terezín prisoners escaped the gas chambers in Poland.

When the war ended in May 1945, 78,000 Czech Jews had been murdered (their names are meticulously written on the walls inside Prague’s Pinkas Synagogue). Holocaust’s horrors, combined with the Bolsheviks’ short-lived love for Israel, made Czechoslovakia in May 1948 one of its staunchest allies in Europe, and it was only thanks to weapons hastily delivered from Brno in Moravia that the young Jewish state managed to fend off the attacks from its Arab neighbours.

Still, the post-war era proved difficult for the Czech Jewish community, who was diminished to 10,000 members. That figure grew even smaller when the communists launched a rabid anti-Semitic campaign that culminated with the monster process against Rudolf Slánský and 10 other Bolsheviks of Jewish origin in 1952 (see: Horáková, Milada).

After 1967, when the East Bloc countries broke their diplomatic relations with Israel, the Czechoslovak secret police launched Operace Pavouk (Operation Spider) — a campaign to register and, if needed, harass every citizen of Jewish origin. The goal was obvious — either to silence Jews with fear, or press them into emigration. This strategy proved sadly successful. When the Bolsheviks were finally swept from power, the once flourishing Czech Jewish community had dwindled to a group of 1.500 scared and grey-haired people.

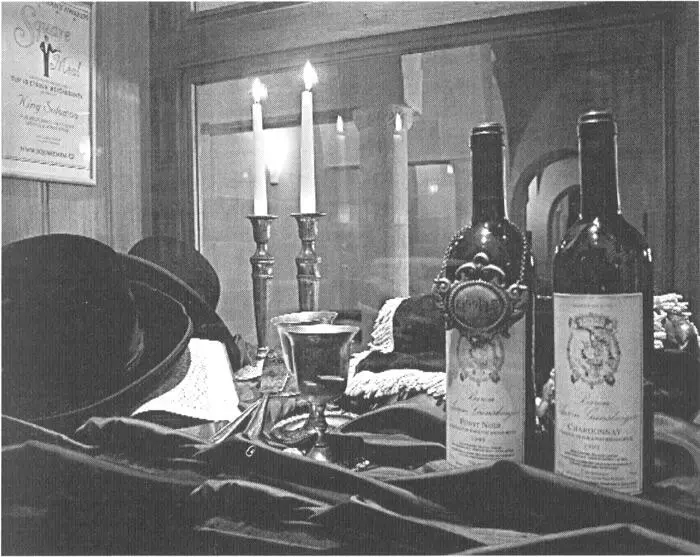

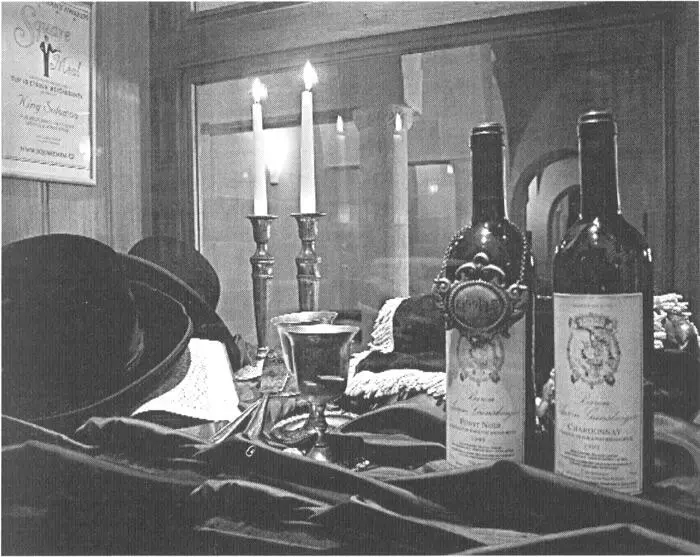

Photo © Jaroslav Fišer

In the aftermath of the Velvet Revolution, support, both moral and financial, flooded in to help the Czech Jews. After nearly a decade without a formal leader, Karol Ephraim Sidon, a respected writer and Charter 77signatory, was named Chief Rabbi of the Czech Republic in 1992. Later, a Yeshiva — a Jewish school — and a Jewish home for the elderly were also established in Prague. Another important step has been taken by Czech authorities, who have returned the Jewish communities most of their pre-war property. Thus, hundreds of buildings, acres of land and religious objects, including Prague’s world-famous Jewish Museum, are securing their rightful owners a financial base, but also the economic responsibility for countless neglected premises.

Yet there has so far not been any Jewish revival in the Czech Republic — for at least two reasons. First, the strong degree of secularisation (see: Religion) also affects the 8,000 — 10,000 Czechs estimated to be of Jewish origin. They simply don’t consider this to be an important issue. And if they do, but happen to live outside Prague, Brno, Karlovy Vary or Plzeň, there is no Jewish community that can receive them.

And second, due to the Czech Jews’ extensive assimilation, there are many mixed marriages. When their children have taken interest in their origin, they have not always been met with open arms by Prague’s Jewish community, which, in religious matters, has been strongly influenced by conservatives hailing from the Mukachevo area of pre-war Czechoslovakia’s most eastern corner (see: Ukrainians). This goes, of course, twice if it’s a Czech goy interested in converting to Judaism.

While American Jews living in Prague in the early 1990s established Bejt (The House), open to followers of both liberal and conservative Judaism, there was a growing dissatisfaction in the city’s Czech-Jewish community with the hard-line approach of Rabbi Sidon and his backers. In the summer of 2004, the subdued grumbling burst out into an open rebellion. The liberals forced Rabbi Sidon to step down as religious head of the Prague community (but he is still Czech Chief Rabbi), which in its turn threw the entire community into a bitter quarrel about the future course.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)