So, next time you are being kicked out of your local hospoda just in the middle of a spirited discussion about everything from football to quantum physics, don’t blame it on the poor innkeeper, but on His Imperial Highness Franz Josef!

As you might have already noticed, the Czech Republic is not an Islamic country (see: Religion), and, therefore, Fridays should be an ordinary working day when business goes on as usual. However, anyone who has tried to sort out a problem at a public office in this country on a Friday afternoon has probably discovered that this day is not an ordinary day at all.

After noon on Friday, most Czech public offices tend to work with even bigger delays and troubles than earlier in the week. This, of course, is not a Czech speciality — public officials all over the Western worldcount down to the weekend. There are, however, few countries where the countdown is performed with greater fervency and matter of course than in the Czech Republic.

If you think this is a legacy of the former communist era, you’re right. During the former regime, it was commonly acknowledged that those who didn’t steal from their (state) employer stole from their families. In practise, this meant that everyone felt entitled to “borrow” bricks, machines, spare parts or whatever his or her company produced, for private use (by the way, how could this be deemed stealing, when everything belonged to the state, which equalled the people?) Subsequently, those who worked in public offices could, without greater pangs of conscience, snatch pens and pencils — but most of all time.

The private sector, which emerged after the Velvet Revolution, has put a more or less effective stop to this deep-rooted tradition. But the public sector, to put it mildly, has not been as successful. Czech state bureaucracyis almost as over-grown as it was under the communists. Symptomatically, some years ago, an elderly fellow was discovered in a dusty room at the Ministry of Interior, and nobody knew that he had been vegetating in the office for several decades.

When Václav Klaus’government started its fight against bureaucracyin the middle of the 1990s, its first step was to establish a committee (which, after all, doesn’t seem all that illogical in the country of Franz Kafka). And still, the army of bureaucrats have lousy wages compared to the private sector, so who can blame them for compensating for a miserable salary by cutting out early on Fridays?

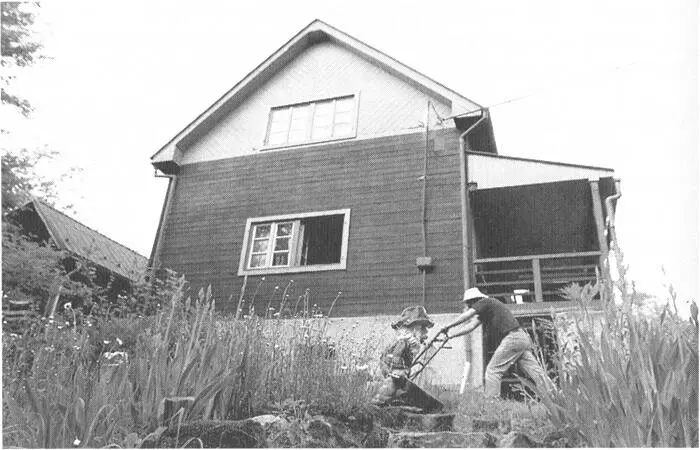

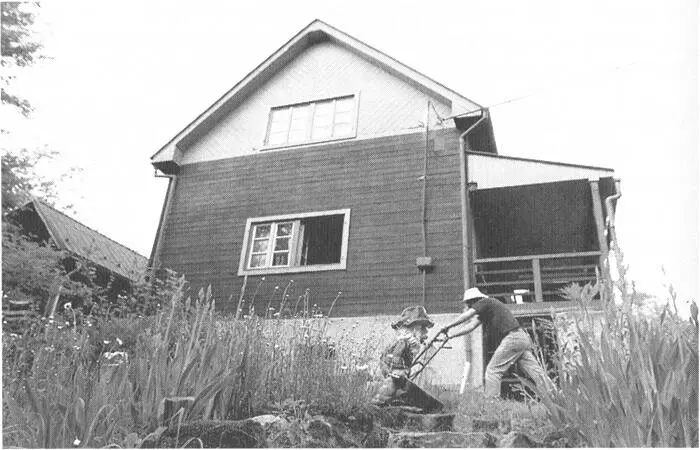

Photo © Jaroslav Fišer

What’s more, the Czechs have quite a good reason for starting the weekend early. Outside Scandinavia, there’s probably no other European nation with more cottage- and cabin-owners than the Czech Republic. Some estimates suggest that there are 1.2 million of these holiday houses (see: Munich Agreement) and that every other Czech family has access to a second home in the countryside. During the communists, it was not uncommon for people to live out a kind of “inner exile” at their cabins, which were their private property. Therefore, all the physical efforts, money and time spent on maintenance were not wasted, because people were investing it in their own property.

Since the Czechs’ passionate love of their country houses hasn’t weakened much after the fall of communism, a foreigneris advised to take one necessary precaution: if you need to sort out an urgent matter in a public office, pray to God it’s not Friday afternoon.

„Fate has left us to clash and to co-operate with the Germans.” This is how František Palacký, the founder of history as a scientific discipline in Bohemiaand one of the spiritual leaders of the nineteenth century Czech national revival once characterized the Czechs’ relations with their great Western neighbour.

However contradictory and ambivalent this may sound, it’s actually a very apt description. On the one hand, the Germans have played a totally irreplaceable part in the cultural and economic development of the Czech nation. On the other, no other country has caused the Czechs greater trauma.

Take a look at a map of Central Europe, and you’ll immediately understand what Palacký had in mind. Today, the Czech Republic’s border with Germany accounts for about 800 kilometres of its 2,300 kilometres of borders. But when you also remember that most of Polish Silesia until 1945 was a part of Germany (Prussia before 1918), and then recall that the Czechs’ southern neighbours, the Austrians, also belong to the Germanic culture, you realize that the Czechs have formed a Slavonic wedge in German territory for almost a millennium.

As some Czech cynics prefer to depict the situation: “We are like the birds that sit in the crocodile’s open jaws!” However wild this parallel might occur to you, it pinpoints some significant differences between the two nations.

Firstly, while the Germans are Central Europe’s largest ethnic group and by far its largest economy, one of the basic ingredients in the Czechs’ national identityis their self-perception as one of the continent’s smaller nations. To use Biblical terms, this is a story about a David who for one thousand years has been living next door to Goliath, and who, at times, has problems with curbing his feeling of inferiority.

Secondly, there is the language barrier, which originally was so insurmountable that the Czech word denoting a German — Němec — derives from the adjective němý , which actually means mute. Thirdly, the justified fear of being politically dominated — and during Second Word War liquidated — by the Germans has repeatedly driven Czech politiciansto seek support and comfort from the Russians. The last attempt to team up with their big Slavonic fellows in the East cost the Czechs 40 years of stagnation, decay and thousands of lost lives (see: Communism).

Yet it would be wrong to describe the Czechs’ relations to the Germans merely as a somewhat troubled neighbourliness. Actually, this is a story about co-habitation. From the thirteenth century onwards, Bohemia and Moraviasaw a constant influx of German settlers. Some of them were merchants invited by the Czech kings, while others were craftsmen offering their services. After the Battle of White Mountain, in 1620, there was also a significant influx of farmers, who took over estates left by exiled Czech Protestants (see: Foreigners). Even an invention as ultra-Czech as Pilsner beershould in reality be credited to Josef Groll, a Bavarian brewer who was headhunted to Western Bohemian Plzeň in 1842.

By 1918, when Czechoslovakia was founded, approximately three million ethnic Germans — more than one third of the population in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia — were living in the country’s Sudeten region. The capital Prague had at that time approximately 30,000 German inhabitants, most of them living in the area near Old Town Square. In addition to the Sudeten Germans, the majority of pre-war Bohemia and Moravia’s 100,000 Jewswere either German speaking or bi-lingual, thus forming a natural bridge between Czech and German culture.

Take, for instance, Max Brod. This Prague-born, German-speaking Jew didn’t only do worldliterature a tremendous favour by saving and publishing his friend Franz Kafka’smanuscripts. Thanks to his German contacts and personal influence, Brod persuaded the Berliner Opera to stage the composer Leoš Janáček’s Jenufa , and he was also instrumental in presenting Jaroslav Hašek’s Good Soldier Švejkto German readers. In both instances, a smashing success in Germany paved the way to global fame.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)