In addition to the historic traumas and the language troubles, there is a social barrier. To many Czechs, only two types of foreigners exist: either those from a Third World country who have come to the Czech Republic to learn how to become a civilized human being, or “businessmen and managers” from Western Europe or America, who have come to exploit the country’s economic wealth. While the members of the first group are tolerated as long as they express their admiration for Czech culture and, not least, leave the country as soon as they have been “civilized”, the Western foreigners are more enigmatic and troublesome.

According to the widespread cliché, Western businesspeople and managers (who were, in a survey in late 2003 elected the most detested professional group in the country, alongside members of the Czech nobility) behave like colonizers in some Third World country. The typical businessman — more seldom a businesswoman — lives in a luxury flat that ordinary Czechs only can dream of, or in Disney land-inspired villaghettos where most natives never set foot. The foreigners don’t drive Škodas or Zhiguliks, but rather fancy cars — which are even singled out by blue number plates. And, most importantly, they earn in a month what a Czech earns in half a year, which is not a great advantage in a nation obsessed by egalitarianism.

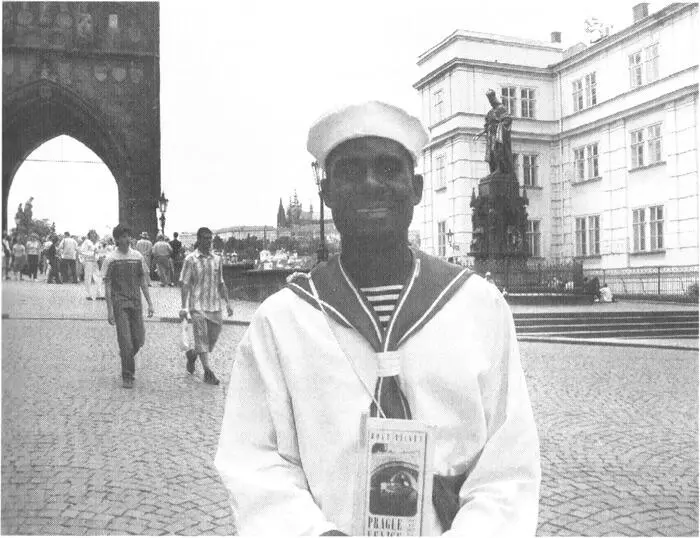

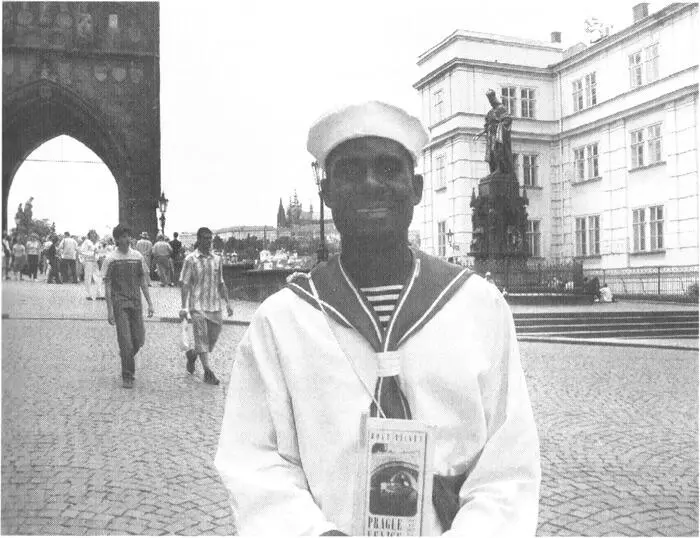

Photo © Terje B. Englund

But then, one might ask, hasn’t the freedom that followed after 1989 managed to curb xenophobic sentiments and stereotypical thinking?

In some aspects, the answer is definitely yes. Open borders and free access to information have done miracles to the atmosphere of musty provincialism that reigned under the communists (see: Ocean). During the last decade, millions of Czechs have travelled abroad and acquired personal experiences from international surroundings. And even more importantly: by now, a new generation of young Czechs not traumatized by the Bolshevik regime’s cheap propaganda, have grown up. Yet one unexpected setback has appeared.

The separation of Czechoslovakia, in 1993, had an impact that is often ignored. After centuries of multicultural co-habitation with Sudeten Germans(who were kicked out in 1945), Jews (who were, largely, killed during the war) and Slovaks(who now had their own state), the Czechs could finally say they were living in a more or less mono-ethnic state (typically, Czech Roma tend not to be counted).

In addition, after the collapse of the Soviet Empire, the Czechs were finally masters of their own house. So why should they now greet foreigners with open arms? Well, for economic reasons, foreign investors had to be tolerated, but as late as in 2003, more than 50 percent of the Czech population, according to a survey, said that they regarded the inflow of foreigners as a negative phenomenon, especially so when it comes to people from Asia and the former Soviet Union. The survey suggested that two thirds of the Czech population would prefer to live in a closed society where they “could solve their problems themselves”.

Does this attitude explain why the “right-wing” government in the first half of the 1990s was so hesitant to sell state industry to foreign investors, as the Hungarianshad done, but instead launched an unsuccessful voucher privatisation program for the country’s citizens? Or was it rather an expression of the golden handsformula — the notion that the Czechs have a God-given talent for creative improvisation (see: Cimrman, Jára)?

In any case, the xenophobic revival in the 1990s has by now, to all appearances, passed its peak. Besides that, the Czechs have, during their turbulent history, demonstrated an amazing capability to adapt to new regimes, so there’s no reason to paint the devil on the wall. The historian Dušan Třeštík probably hit the nail on the head when he stated that the Czechs have already become completely normal Europeans. “The only problem is that they’re not yet aware of it.”

To the citizens of the Habsburg empire, Franz Josef I — who ruled his multi-national subjects with a firm hand for an incredible period stretching from 1848 to 1916 — was something like Queen Victoria to the British: a seemingly immortal symbol of the empire’s stability, the predictability of its conservative politics and the moral valuespreached by the Catholic Church (see: Religion).

However, when the First World War ended in late 1918 and the Danube Empire fell apart, Franz Josef was soon forgotten by his former Slavonic subjects, not least by the Czechs, who had lost more than two hundred thousand young men in a meaningless war they never supported. Neither had they forgotten that the Emperor, or Mister Procházka , as they spitefully called him (a newspaper once printed a photo of the Emperor in Prague with the caption Procházka na mostě , or “A Walk on the Bridge”), for letting himself, in 1867, be crowned as king of the Hungarians, while he didn’t take the trouble to go to Prague to be crowned as the king of the Czechs.

And when his nephew, Franz Ferdinand — the unlucky fellow in Sarajevo — married a lady from the Czech gentry, Žofie Chotková, both the Emperor and his court reacted with unconcealed horror. Franz Ferdinand was even pressed to accept the condition that the children of such an “unequal” marriage would have no rights to ascend to the imperial throne.

Small wonder, then, that the citizens of newly-established Czechoslovakia exceeded one another in smashing statues of the former Emperor. Jaroslav Hašek, the author of the tales about the good soldier Švejk, uses one episode to pinpoint the Czechs’ aversion towards Franz Josef: when flies “decorate” the Emperor’s portrait in a hospoda with their waste products, the Czech innkeeper (and millions of readers with him) hardly manages to hide his pleasure, while the Austrianundercover agent goes bananas and arrests the poor guy.

Yet Franz Josef has left one tradition that still characterizes the Czechs’ daily life. One of Franz Josef’s allegedly numerous virtues was his great diligence. Thus, in all the 68 years he ruled, the Emperor went to bed early (okay, often with his mistress), and — even more importantly — woke up and started working at an almost ungodly early hour.

Some pundits claim that the real reason was not diligence, but rather the Emperor’s long-lasting problems with insomnia. Be this as it may, the consequence was inevitable: when Franz Josef was busily working at six o’clock in the morning, his staff and administration were also busily working at six o’clock. And when state bureaucrats all over the empire jumped out of bed before the sun rose, private industry, trade and transport couldn’t be far behind. In short: the Austro-Hungarian empire must have been hell for all of us late sleepers.

Almost a century after Franz Josef was promoted to eternity, this awful tradition is still frightfully alive and kicking in the Czech Republic. In most hospitals, for instance, patients are woken up at six o’clock, even if the doctor’s visit is scheduled only at nine. In schools, lessons start at eight o’clock, while at the universities, lectures might begin even earlier. Also, in many Czech factories, production starts at least one hour earlier than is common in Western and Northern Europe. The government of Vladimír Špidla, which was installed in 2002, took this perversion so literally that it started some of its meetings at six o’clock in the morning!

To be fair, this tradition certainly doesn’t represent a serious problem, but it affects one, not insignificant, layer of the Czech society: beerdrinkers. To give the millions of Czechs who spend the evening in a local hospoda a chance to sober up before work starts at six o’clock the next morning, most pubs mercilessly close at ten o’clock in the evening — i.e., at a time when people in other parts of Europe have just started the evening.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)