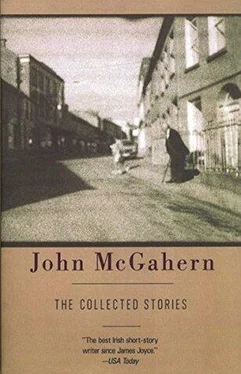

John McGahern - The Collected Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John McGahern - The Collected Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Collected Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Collected Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Collected Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Collected Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Collected Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When he did not appear at the mill the first morning after the holiday, the foreman and one of the men went to the parsonage. The key was in the front door, but there was no answer to their knocking. They found him just inside the door, at the foot of the stairs. In the kitchen two places were laid at the head of the big table. There was a pair of napkins in silver rings and two wine glasses beside the usual cutlery. A small turkey lay in an ovenware dish beside the stove, larded and stuffed, ready for roasting. An unwashed wilting head of lettuce stood on the running board of the sink.

As an announcement of a wedding or pregnancy after a lull seems to provoke a sudden increase in such activities, so it happened with the Sergeant’s early retirement from the Force. The first to follow was Guard Casey. He had no interest in land and used his gratuity to pay the deposit on a house in Sligo. There he got a job as the yardman in a small bakery, and years of intense happiness began. His alertness, natural kindness, interest in everything that went on around him, made him instantly loved. What wasn’t noticed at first was his insatiable thirst for news. Some of the bread vans went as far as the barracks, and it seemed natural enough that he should be interested in places and people he had served most of his life. In fact, these van men took his interest as a form of flattery, lifting for a few moments the daily dullness of their round; but then it was noticed that he was almost equally interested in people he had never met, places he had never been to. In a comparatively short time he had acquired a detailed knowledge of all the van routes and the characters of the more colourful shopkeepers, even of some who had little colour.

‘A pure child. No wit. Mad for news,’ was the way the passion was affectionately indulged. ‘He should be fed lots. Tell him plenty of lies.’ But he seemed to have an unerring sense of what was fact and what malicious invention.

‘Sunday is so long. It’s so hard to put in.’

Guard Casey kept the walk and air of a young man well into his seventies and went on working at the bakery. It was a simple fall crossing the yard to open the gates one wet morning that heralded an end, a broken hip that would not heal. He and his family had grown unused to one another over the years. They now found each other’s company burdensome, and it was to his relief as well as theirs when it was agreed that he would get better care in the regional hospital when it was clear that he wasn’t going to get well, as everything but his spirit was sinking. Then his family, through their religious connections, found a bed for him in St Joseph’s Hospice of the Dying in Dublin. It was there he was visited by the Sergeant’s son, who had heard that he missed company.

‘They’re nearly all gone now anyhow, God have mercy on them. Is me Oisín i ndiadh na feinne ,’ he laughed.

‘Wouldn’t you think when they’re so full of religion that they’d have shifted themselves this far to see you?’ It was open criticism of his family.

‘No, not at all. It’s too far.’ He lifted his hand as if to clear the harshness which seemed to take on an unpleasant moral note in the face of this largeness of spirit. ‘No one in their right mind travels so far to follow losing teams. And this is a losing team.’ He started to laugh again but was forced to stop because of coughing. ‘Still, I’ve known the whole world,’ he said when he recovered.

Johnny justified Brother Benedict’s account of his ability to Colonel Sinclair by winning a scholarship to university the following year.

‘You’ll be like the rest of the country — educated away beyond your intelligence,’ was the father’s unenthusiastic response, and they saw very little of one another over the next few years. Johnny spent vacations in England working on building sites and in canning factories around London. A good primary degree allowed him to baffle his father even further by continuing postgraduate study in psychology, and he was given a lectureship in the university when he completed his doctorate. Then he obtained work with the new television station, first in an advisory role, but later he made a series of documentary films about the darker aspects of Irish life. As they were controversial, they won him a sort of fame: some thought they were serious, well made, and compulsive viewing, bringing things to light that were in bad need of light; but others maintained that they were humourless, morbid, and restricted to a narrow view that was more revealing of private obsessions than any truths about life or Irish life in general. During this time he made a few attempts to get on with his father, but it was more useless than ever. ‘There must be rules if there’s to be any fairness or freedom,’ he argued the last time they met.

The tide that emptied the countryside more than any other since the famine has turned. Hardly anybody now goes to England. Some who went came home to claim inheritances, and stayed, old men waiting at the ends of lanes on Sunday evenings for the minibus to take them to church bingo. Most houses have a car and colour television. The bicycles and horses, carts and traps and sidecars, have gone from the roads. A big yellow bus brings the budding scholars to school in the town, and it is no longer uncommon to go on to university. The mail car is orange. Just one policeman with a squad car lives in the barracks.

The tide that had gone out to America and every part of Britain now reaches only as far as a bursting Dublin, and every Friday night crammed buses take the aliens home. For a few free days in country light they feel important until the same buses take them back on Sunday night to shared flats and bed-sits.

Storage heaters were installed in the church in the village because of the dampness but the damp did not leave the limestone. The dark evergreens shutting out the light were blamed and cut down, revealing the church in all its huge, astonishing ugliness amid the headstones of former priests of the parish inside the low wall that marked off a corner of Henry’s field. The damp still did not leave the limestone, but in spite of it the church is full to overflowing every Sunday.

As in other churches, the priest now faces the people, acknowledging that they are the mystery. He is a young priest and tells them that God is on their side and wants them to want children, bungalow bliss, a car, and colour television. Heaven is all about us, hell is in ourselves and in one moment can be exorcized. Many of the congregation chat with one another and read newspapers all through the Sacrifice. The words are in English and understandable. The congregation gives out the responses. The altar boys kneeling in scarlet and white at the foot of the altar steps ring the bell and attend the priest, but they no longer have to learn Latin.

No one beats a path to the presbytery. The young priest is seldom there and has no housekeeper. Nights, when he’s not supervising church bingo, he plays the guitar and sings at local hotels where he is a hit with tourists. He seldom wears black or the Roman collar. To show how little it means to him, one convivial evening in a hotel at Lough Arrow he pulled the collar from his neck and dropped it into the soup. When the piece of white plastic was fished out amid the laughter, it was found to have been made in Japan.

A politician lives outside the village, and the crowd that once flocked to the presbytery now go to him instead. Certain nights he holds ‘clinics’. They are advertised. On clinic nights a line of cars can be seen standing for several hundred yards along the road past his house, the car radios playing. On cold nights the engines run. No one thinks it wasteful any more. They come to look for grants, to try to get drunken driving convictions squashed, to get free medical cards, sickness benefit, to have planning application decisions that have gone against them reversed, to get children into jobs. As they all have votes they are never ‘run’.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Collected Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Collected Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Collected Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.