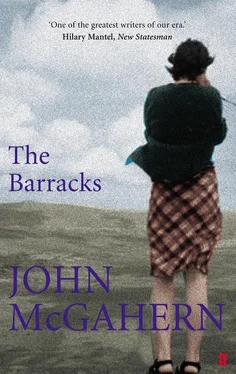

John McGahern - The Barracks

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John McGahern - The Barracks» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Faber & Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Barracks

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber & Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Barracks: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Barracks»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Barracks — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Barracks», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

John McGahern

The Barracks

To

JAMES SWIFT

1

Mrs Reegan darned an old woollen sock as the February night came on, her head bent, catching the threads on the needle by the light of the fire, the daylight gone without her noticing. A boy of twelve and two dark-haired girls were close about her at the fire. They’d grown uneasy, in the way children can indoors in the failing light. The bright golds and scarlets of the religious pictures on the walls had faded, their glass glittered now in the sudden flashes of firelight, and as it deepened the dusk turned reddish from the Sacred Heart lamp that burned before the small wickerwork crib of Bethlehem on the mantelpiece. Only the cups and saucers laid ready on the table for their father’s tea were white and brilliant. The wind and rain rattling at the window-panes seemed to grow part of the spell of silence and increasing darkness, the spell of the long darning-needle flashing in the woman’s hand, and it was with a visible strain that the boy managed at last to break their fear of the coming night.

“Is it time to light the lamp yet, Elizabeth?” he asked.

He was overgrown for his age, with a pale face that had bright blue eyes and a fall of chestnut hair on the forehead. His tensed voice startled her.

“O Willie! You gave me a fright,” she cried. She’d been sitting absorbed for too long. Her eyes were tired from darning in the poor light. She let the needle and sock fall into her lap and drew her hand wearily across her forehead, as if she would draw the pain that had started to throb there.

“I never felt the night come,” she said and asked, “Can you read what time it is, Willie?”

He couldn’t see the hands distinctly from the fire-place. So he went quickly towards the green clock on the sideboard and lifted it to his face. It was ten past six.

The pair of girls came to themselves and suddenly the house was busy and full with life. The head was unscrewed off the lamp, the charred wicks trimmed, the tin of paraffin and the wide funnel got from the scullery, Elizabeth shone the smoked globe with twisted brown paper, Willie ran with a blazing roll of newspaper from the fire to touch the turned-up wicks into flame.

“Watch! Watch! Outa me way,” he cried, his features lit up with love of this nightly lighting. Hardly had Elizabeth pressed down the globe inside the steel prongs of the lamp when the girls were racing for the windows.

“My blind was down the first!” they shouted.

“No! My blind was down the first!”

“Wasn’t my blind down the first, Elizabeth?” they began to appeal. She had adjusted the wicks down to a steady yellow flame and fixed the lamp in its place — one side of the delf on the small tablecloth. She had never felt pain in her breasts but the pulse in the side of her head beat like a rocking clock. She knew that the aspirin box in the black medicine press with its drawn curtains was empty. She couldn’t send to the shop for more. And the girls’ shouts tore at her patience.

“What does it matter what blind was down or not down? — only give me a little peace for once,” was on her lips when her name, her Christian name — Elizabeth — struck at her out of the child’s appeal. She was nothing to these children. She had hoped when she first came into the house that they would look up to her as a second mother, but they had not. Then in her late thirties, she had believed that she could yet have a child of her own, and that, too, had come to nothing. At least, she thought, these children were not afraid of her, they did not hate her. So she gripped herself together and spoke pleasantly to them: they were soon quiet, laughing together on the shiny leatherette of the sofa, struggling for the torn rug that lay there.

Una was eleven, two years older than Sheila, almost beautiful, with black hair and great dark eyes. Sheila was like her only in their dark hair. She was far frailer, her features narrow and sensitive, changeable, capable of looking wretched when she suffered.

They were still playing with the rug when Elizabeth took clothes out of a press that stood on top of a flour bin in the corner and draped them across the back of a plain wooden chair she turned to the fire. They stopped their struggling to watch her from the sofa, listening at the same time to find there was no easing in the squalls of rain that beat on the slates and blinded windows.

“Daddy’ll be late tonight?” Sheila asked with the child’s insatiable and obvious curiosity.

“What do you think I’m airin’ the clothes for, Sheila? Do you hear what it’s like outside?”

“He might shelter and come home when it fairs?”

“It has no sound of fairin’ to me — only getting heavier and heavier.…”

They listened to the rain beat and wind rattle, and shivered at how lucky they were to be inside and not outside. It was wonderful to feel the warm rug on the sofa with their hands, the lamplight so soft and yellow on the things of the kitchen, the ash branches crackling and blazing up through the turf on the fire; and the lulls of silence were full of the hissing of the sap that frothed white on their sawed ends.

Elizabeth lowered the roughly made clothes-horse, a ladder with only a single rung at each end, hanging high over the fire, between the long black mantelpiece and the ceiling.

“Will you hold the rope for me?” she asked the boy and he held the rope that raised and lowered the horse while she lifted off a collarless shirt and felt it for dampness. She spread it on the back of a separate chair, the sleeves trailing on the hearth. He pulled up the horse again, hand over hand, and fastened the loop of the rope on its iron hook in the wall.

“Do you think will he be late tonight?” he asked.

“He’s late already. You can never tell what hold-up he might have. Or he might have just taken shelter in some house. I don’t know why he should have to go out at all on a night like this. It makes no sense at all! O never join the guards when you grow up, Willie!”

“I’ll not,” he answered with such decision that she laughed.

“And what’ll you be?”

“I’ll not join the guards!”

They looked at each other. She knew he never trusted her, he’d never even confide his smallest dream in her. She seemed old to him, with her hair gone grey and the skin dried to her face. Not like the rich chestnut hair of his mother who had died, and the lovely face and hands that freckled in summer.

“It’s time you all started your homework,” Elizabeth ordered. “If your father sees a last rush at night there’ll be trouble.”

They got their schoolbags and stood up the card-table close to the lamp on the laid table. There was the usual squabbling and sharpening of pencils before they gave themselves to the hated homework, envious of their stepmother’s apparent freedom, aware of all the noises of the barracks. They heard Casey, the barrack orderly, open the dayroom and porch doors, and the rattle of his bucket as he rushed out for another bucket of turf: the draughts banging doors all over the house as he came in and the flapping of his raincoat as he shook it dry like a dog in the hallway, then his tongs or poker thudding at the fire after the door had closed.

“Will I be goin’ up to sleep with Mrs Casey tonight?” Una lifted her head to ask.

“I don’t know — your nightdress is ready in the press if you are,” she was answered.

“Guard Casey said this evenin’ that I would,” the child pursued.

“You’ll likely have to go up so. You’ll not know for certain till your father comes home,” she was abruptly told. Elizabeth was tired to death, she could not bear more questions.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Barracks»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Barracks» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Barracks» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.