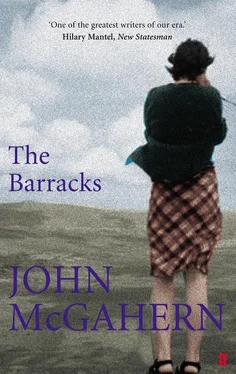

John McGahern - The Barracks

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John McGahern - The Barracks» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Faber & Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Barracks

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber & Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Barracks: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Barracks»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Barracks — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Barracks», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Oh, things get too terrible sometimes, Willie,” she blurted suddenly out and when she saw his worried amazement she was sorry. She lifted the bucket. When she’d have dragged as far as the scullery table she’d try to give him all her attention till the others would get home, she promised.

The school holidays ended in early September, the kitchen emptier all the mornings and afternoons, and Mrs Casey began to come practically every day and to stay for hours. She had nothing to do, she complained.

“I didn’t mind at all,” she said; one morning Elizabeth had praised her for taking care of the house while she was in hospital. “There was great excitement, them all were good and helped, and I felt I was needed — it’s when you have nothin’ to do and start thinkin’ that’s the worst.

“I’ll go off me rocker some day I’m alone up in that elephant of a house, that’s the God’s truth,” she cried. “If you had a child or something you’d be better able to knuckle down! But when you have nothin’, that’s the thing! I was at Ned to adopt one out of the Home but he wouldn’t hear of it. They’d have bad blood or wild, their father’s or mother’s blood, he said. What does he care? He’s down in the dayroom here or at court or out on patrol most of the time but where am I?”

Elizabeth didn’t know what to do, only let her cry. She liked her, but she was afraid the younger woman was beginning to depend too much on her, and she could drag like deadweight. Mullins’s wife and Brennan’s were hard and vulgarly sure of their positions, always ferociously engaged in some petty rivalry or other, but they were too full of their own things to ever drag. The most they’d want was to make some material use out of you, and it was always easier to deal with them than such as Mrs Casey. You’d only to meet their demands on the one level, and perhaps a person had always to stay on that level to survive as untouched as they were. She’d try and tell Mrs Casey that she was running through a bad time, as every one did, and that it would pass. Though it’d be quite useless as anything else. She’d better make tea. The one thing was that her own situation didn’t seem so desperate when it was confronted with such as this.

The days grew colder and there came the first biting frosts, the children having to wear their winter stockings and boots, some lovely nights in this weather, a big harvest moon on the lake, and the beating whine of threshing-machines everywhere, working between the corn-ricks by the light of the tractor headlamps. The digging of the potatoes began. And there was great excitement when apples were hung from the barrack ceiling for Hallowe’en and nuts went crack under hammers on the cement through the evening. All Souls’ Day they made visits to the church, six Our Fathers and Hail Marys and then outside to linger awhile beneath the bell-rope before entering again on another visit, and for every visit they made a soul escaped out of purgatory.

There had only been one month of peace with Quirke after the day Reegan had been caught spraying, though he had kept it from Elizabeth till it erupted again into the open that November. Quirke had paid an early morning inspection, and afterwards Reegan came up to her in the kitchen in a state of blind fury.

“The bastard! The bastard! I’ll settle that bastard one of these days,” he started to grind and she saw his hands clench and unclench and touch unconsciously the sharp, red stubble on his face.

“What happened?” she asked when he was quieter.

“He did an inspection this mornin’ and after the others had gone he said, ‘There’s something I want to tell you, Reegan,’ and I like a gapin’ fool opened me big mouth and said, ‘What?’ So he stared me straight in the face and said, ‘Let me tell you one thing, Reegan: never come down to this dayroom again unshaven while you’re a policeman!’ and he left me standin’ with me mouth open.”

She saw he desperately needed to tell some one: to ease the hurt by telling, cheapen and wear out his passion by telling, scatter it out of his mind where it was driving him to the brink of madness. Though she found the tremor of hatred unnerving, his face purple as he shouted, “Never come down to this dayroom unshaven again while you’re a policeman, Reegan! Never come down to this dayroom unshaven again while you’re a policeman, Reegan!”

“You didn’t do anything at all?” she asked.

“Nothin’. It took me off me feet, that tough is a new line from Quirke. Though I’d probably have done nothin’ anyhow,” he was quieter, he began to brood bitterly now. “I’d not be thirty bastardin’ years in uniform if I couldn’t stand before barkin’ mongrels and not say anything. It’s either take them by the throat and get sacked or stop with your mouth shut, and they know they’ve got you in the palm of their hand. Though they couldn’t sack me now, I’m just thirty years in this slave’s uniform, they’d have to ask me to resign and give me a pension. You can’t victimize an old Volunteer these days!” he began to laugh and then swiftly it turned to rage again. “That bastard! That ignoramus! Never come down to this dayroom again unshaven while you’re a policeman, Reegan!” he shouted.

“If you want to get out of the police altogether I don’t mind. Don’t let me stand in your way. I was afraid of it before but I don’t think it makes any difference any more,” Elizabeth said.

“You don’t mind?” he came close to stare.

“No. You can send in your resignation, whenever you wish.”

“And what’ll we do then?”

“Whatever you think best, it’s not for me,” she shuddered from the responsibility. “It won’t be my decision, it’ll be up to you, though I’d give any help. You know that, it must be your decision.”

“I thought after the summer that we’d have enough to buy and stock a fair farm. That’s what I was brought up to, Reegans as far as you can go worked a farm, not till 1921 did this bastardin’ uniform show itself. With the pension we’d not be worked too much to the bone on a farm, and you’d be your own boss anyhow.”

“Whatever you think, that seems good,” she nodded, one thing was much the same as the next to her, this game of caring was only something she felt she owed him to play.

“But Jesus there’s one thing, Elizabeth,” he swore. “There’ll be no goin’ quiet, that’s certain. I’ll do for that bastard before I go. Never come down to this dayroom unshaven again while you’re a policeman, Reegan! There’ll be no goin’ quiet, that’s the one thing that’s sure and certain,” he said between clenched teeth and took his greatcoat and cap to go out on another patrol.

The heavy white frost seemed over everything at this time, the drum of boots on the ground hard as concrete in the early mornings, voices and every sound haunting and carrying far over fields of stiff grass in the evenings. The ice had to be broken on the barrels each morning. It was so beautiful when she let up the blinds first thing that, “Jesus Christ”, softly was all she was able to articulate as she looked out and up the river to the woods across the lake, black with the leaves fallen except the red rust of the beech trees, the withered reeds standing pale and sharp as bamboo rods at the edges of the water, the fields of the hill always white and the radio aerial that went across from the window to the high branches of the sycamore a pure white line through the air.

And then she’d want to go out and lift her hot face and throat to the morning. But it would be only to find her eyes water and every desire shrivel in the cold. She wasn’t able to do that any more, that was the worst to have to realize; and it was driven home like nails one evening she was alone and the first heart attack struck while she was lifting flour out of the bin; she managed to drag herself to the big armchair and was just recovered enough to keep them from knowing when they came home.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Barracks»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Barracks» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Barracks» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.