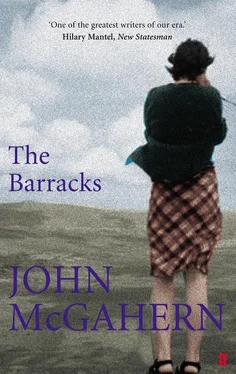

John McGahern - The Barracks

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John McGahern - The Barracks» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Faber & Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Barracks

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber & Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Barracks: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Barracks»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Barracks — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Barracks», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

None of the others ever went on holidays. They spaced out their leave for the turf and potatoes, little jobs in their gardens and house, bringing timber from the woods in the rowboat, and the excursions they made with their wives to town, mostly to buy clothes and shoes.

Elizabeth didn’t want to go away. She felt more than ever that she’d never leave this barracks again, here she was meant to end her life, and she grew more sure of that with every new day.

She put turf and some wood on the fire while Reegan hammered, took down the flickering Sacred Heart lamp and filled it with oil, put a cloth and delf on the table and she had most of the jobs done.

There was such deep silence in the kitchen when Reegan would stop hammering to examine his work, the men sent home from the woods and the quarry, the constant drip of rain on the window-sills outside. She was completely alone with Reegan. She thought it might be the only right time she’d ever get to tell him about the money of her own she’d always kept, if she didn’t tell it now it’d never be told. It had constantly preyed on her mind ever since she took it out of the locked trunk to bring to hospital. She’d spent hardly any of it there and if she didn’t get rid of it soon it’d possess her for the rest of her life.

Fear must have made her gather it the first day. She’d seen scraping all her youth, having to wait for winter boots, till the calf or litter of pigs was born, worry over money gnawing at the happiness of too many evenings in childhood; she’d seen her mother and father bitter over each other’s spending, and she never wanted to be under its rule again. She’d saved out of her first wages. But when she’d saved enough to give her few desires some freedom she didn’t trouble more. If she had enough to buy some new clothes or go a place or bring something to someone she loved, she was happy. It was not miserliness, there’s such fearful unhappiness at the heart of all miserliness, no trust or love, and the passion to live for ever cheapened into the bauble of providing against the wet day, the lunacy of building an outer wall against something that’s impregnably entrenched in every nerve and cell of the body.

She hated to either borrow or lend, she’d give money but not lend, she felt any relationship based and bound by money more loathsome than rotten flesh. How her nerves would shiver and creep when a girl out of the hospital would say to her, “I’m not forgettin’ about that loan, Elizabeth. I’ll be able to pay you back soon.”

“No, no, no,” she’d want to burst out. “Keep it, do what you like with it, I don’t want to see it again,” and how hard it was to discipline herself and say the conventional thing that’d be accepted and not cause hatred. So she was never without money, enough to buy her anything she’d want or even indulge sudden whims without having to worry or consider. It left her free, she’d try to reason, but it went far beyond any reasoning. She even kept it to herself when she married. With that money she could be in London in the morning. It was dishonest. They were living together in this barracks, tied in the knot of each other; they had accepted the burden of her, she the burden of them, and they should have at least every exterior thing in common. They had all failed or were afraid to attempt to live alone, could any one of them endure total loneliness or silence or neglect, and enough had to be kept back by people living together without extending it to something as common and mangy with sweat as money. She’d have to put it right, tell Reegan, force him to take the money.

He had finished the chair. His face was flushed and happy and he was hooking the clasp of his tunic at the throat. He showed her the chair for her praise, and she pretended to test it and inspect the joinings.

“It’s as good as new,” she praised.

“Aw, not as good as new, but it’ll do a turn. It’ll take more than natural abuse to smash it this time,” he showed his real pleasure in the diminishment.

“I think it couldn’t be better,” she said, and they sat together to gaze into the fire and out at the grey, steady rain. It wound down, stirred by no breath of wind, barely fouling the mirror of the calm river.

“It’d put you to sleep, that rain,” he said.

“It might be good for the fishing though,” she answered.

“It should, it’s never bad on a dull, rainy evenin’, you always get bites of something.”

The silence resumed, the kettle murmuring, the drip-drip of rain on the sills. She stirred the fire with the tongs. She tried to get herself to tell about the money, and then she said awkwardly out of the continuing silence, “There’s something I want to tell you that’s not easy.”

She saw how awful a way it was to break anything, when the words were out: his body went tense, fear came in the eyes. His jerky, “What?” seemed asked more with the muscles than the voice. What could she have to tell him that wasn’t easy, it couldn’t be pleasant, and he wished he didn’t have to hear.

She wished she hadn’t to tell, but she was driven. There was no reason to this crying need to speak: what did he matter any more than she mattered; he’d have to die into whatever there was too, and all things were believed to be changed in new light then. It made no sense, this need to speak, she’d be as well to try to get the raindrip from the sycamore leaves outside to understand.

She might as well be honest about why she wanted to speak her truth. It was to ease her own mind. What could it do but disturb his peace or at best leave him indifferent? The Church knew an old trick or two when she said you make your confession to God, and not to the priest in the box, whose understanding or misunderstanding has nothing whatever to do with the Sacrament. But how humanness entered everything. She’d go steeled and prepared to tell the truth to God and end in the squalid drama of trying to get a name printed on a card outside the box, a voice in the darkness, a smell of after-shave lotion to understand.

She could steel herself, make herself cold as death and inhuman to try to bear witness to the truth, but she was so weak that at its first intimation her preparations and disciplines would crumple up, and she’d become only more truly human than before she ever set out. Oh irony of ironies! The road away becomes the road back.

There was no end to thinking and she could even think away the need to think. An age of thought can pass before the mind and be lost in the same flash. What she had to do now was state not reason; state it and suffer it in her human self. She had pondered on it for months up to this moment, reasoned it more than once away, and still the need remained.

Reegan was watching her impatiently, fretting at the wait.

“It’s money,” she began. “I’ve some money that I never told you about. I meant to and as time went it got harder to tell. I was afraid you mightn’t understand.”

She broke down, beginning to sob with shame and squalor. Nothing struck Reegan for a moment. He’d been tensed for something painful, and now that this was all he was taken by surprise. He’d often wondered if she’d spent all she had earned in London but they never seemed close enough for him to be able to ask without fear of offence. She was crying now.

“Don’t, Elizabeth,” he said. “It doesn’t matter. It’s your own money and nobody ever asked you to tell. It’s your own to tell or not to tell and has nothin’ got to do with anybody else.”

She heard what he said, it did not matter. She tried to pull herself together, out of this breakdown. She’d have to try and see it through to the end once she’d started.

“No, that’s not right. When I didn’t want to take money for clothes you used say,’ What’s mine is yours. It’s there for you to take as much as me’,” she said.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Barracks»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Barracks» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Barracks» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.