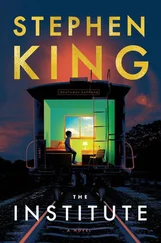

“All right, the mansion is out.”

“Why not a couple of floors in the Garrett Building? The one I already have on Massachusetts Avenue — in Washington, I’m talking about.”

“A little slower please. You’re way ahead of me.”

“I have to have this Washington branch on account of the things I sell, or my companies sell. They all involve patents, and patents have to be defended at hearings of various kinds. They also involve legislation, tariffs, authorizations of one kind or another, appropriations, and so on. All that means lawyers, lobbyists, agents, gumshoes, goons, and God-knows-what. They have to have offices with phones, secretaries, and messengers. So I bought this building down there, reserved two floors for them, and rented out the other floors — ten, actually. So, O.K., why can’t you take two? Or three? Or however many you’ll need? I’ll make the building over to you. You’ll rent the other floors out, and the rent you get will be a nice lift for your budget. Is that an idea or not?”

“I’m sorry, but I have to say no.”

He looked very startled and stared at me for some time. After several moments, after he had said, “You quite surprise me” and in other ways betrayed that he had been set back on his heels, he finally asked: “Why do you say that?”

“It’s against the law, Mr. Garrett.”

“It’s what?”

“You can’t endow a foundation and then rent yourself office space. You could until recently, but they found it was being used as a loophole, some tricky angle on taxes. So Congress closed it.”

“Well! Thanks for warning me.” He leaned back, staring at his desk top. His chair squeaked. He pressed a button. When Miss Immelman came in, he said: “Get on this chair, will you? Have it greased or something.”

“Yes, Mr. Garrett, I will.”

Then to me: “What would be your idea?”

“Why — I have no idea yet. I may get one, though. Give me a little time.”

“Why don’t we break for lunch? I’d invite you to the apartment, but I’m expecting someone there. You’ll find the hotel good — the Du Pont, I mean. Quite good, as a matter of fact. Damned good.”

“The Du Pont is fine. I’ll be staying there.”

After lunch I said: “If you insist on downtown Washington — and though I’m caught by surprise, I have to admit it does make sense — I would say you should buy us a building, let me take two floors, and rent out the rest. I wouldn’t think the right place would be too hard to find.”

“Okay, will you handle it?”

“I’ll do my best and keep you informed.”

What he meant, I wasn’t quite sure of, because if finding a building for him was what he had in mind, I knew no more about buildings than a new-born grasshopper did. But that seemed to be it, and I added: “I think I should give you a weekly progress report, with discussions in between — if, as, and when.”

“Where’d you get that expression — ‘if, as, and when’?”

“It’s one my mother was fond of. Why?”

“It’s one bankers use.”

“She was quite a banker herself. I wouldn’t say she was fond of money, but money was fond of her.”

“Money’s no fool.”

He looked at me sharply, and from there on in, I thought his manner toward me changed.

The next day we assembled at his office for the trip down to Dover — Ned Bramwell, his top Delaware lawyer; four or five men from his office who were to sign as incorporators, and Sam Dent, chief lawyer for the entire ARMALCO outfit, who had come up from Washington. He was the pleasantest discovery of the trip. Older than me, around forty-five, I’d say, but tall, well bred and dressed — definitely my kind of guy. We took to each other at once, but from the look on his face when the Institute was mentioned, I knew he had pretty well guessed the relationship between its patron saint and the man who was going to direct it. We drove to Dover in two cars, I in the front seat with Dent in his car, the two youngest men from the office in back, and the rest in Bramwell’s car. The whole process took no more than an hour as we moved from office to office in the capitol, signing and shuffling papers. Once there was a slip I had to sign, which I did. Then we had a late lunch. Bramwell took his gang off, and Dent and I had a long drink and talk. It turned out that he had seen me play football. We drove back to Wilmington and he dropped me off at the Du Pont. I called Mr. Garrett to ask him when he wanted to see me, but he said we were done. “However,” he said, “keep in touch, will you — if, as, and when? And get on that building at once.”

“I shall indeed, sir.”

But my heart was already jumping with the anticipation of seeing her that night.

The smell of roast beef rose in my nose as soon as I unlocked the door. No light was on, but a hand raised up from behind one of the sofas and a voice said huskily: “Well, hello, hello!”

I was hungry for her. My arms ached for her, and hers went around me as I knelt to press her close, inhale her, pat her, and at last kiss her. She whispered: “We’re eating in tonight — roast beef, which won’t be a surprise; as you must be able to smell it. But everything else will be. I promise you, though, it will be just right for what ought to go with it.”

I knew nothing to say to that except hold her closer. She moved so I could sit beside her, and then I saw the gingham apron she had on over her dress. I laughed, and she asked: “Well, what’s so funny? I love you, that’s all.”

“It makes you look cute.”

“It makes me want to snuggle.”

“Okay, then snuggle.”

So she snuggled and time went by. At last she drew a deep breath and said it was time to talk. “I’m so proud of you,” she said.

“What have I done for you to be proud of?”

“The impression you made on him. He called to tell me.”

“What impression?”

“You said no to him, for one thing. He’s so used to yes men around him that he couldn’t believe his ears at first. He was still gasping when he called me. Said you threatened to put him in jail.”

“I did no such thing, and he said no such thing.”

“Well, it was something.”

“All I did was warn him that his idea was against the law.”

“Yes, that was it.”

“I said not one word about jail.”

“I think that was his little joke. He has an odd sense of humor. But that wasn’t all. Lloyd, you impressed him no end, the way you had done your homework, as he called it. You had things at your fingertips. Also, he says you come by your brains honest. How did your mother get in it?”

“I mentioned that money liked her.”

“And he fell for her plenty.”

“I happened to use an expression of hers and it seemed to catch his ear.”

“What expression?”

“ ‘If, as, and when.’ ”

“Why would that catch his ear?”

“It’s one bankers use.”

“Oh!... Oh! Well, that would catch his ear.”

“Speaking of ears... I began to nibble on hers, but she pushed me off.

“No, please,” she said a little breathlessly. “There’s more.”

“Say on, pretty creature, say on.”

“He was suspicious of you before — half-liked you but thought you were much too cheeky to really have any brains. But your saying no to him caught his attention, and suddenly he’s now sold all the way, even on you, as the person who should be in charge. Isn’t that wonderful?”

“I thought I detected a change in his manner.”

But I must have seemed withdrawn or hesitant or something short of joyous, because suddenly she pulled away in the dark and asked: “Well, for heaven’s sake, what is it now ?”

Читать дальше