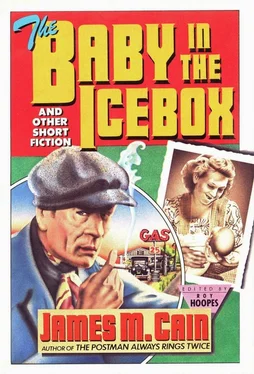

James M. Cain

The Baby in the Icebox and Other Short Fiction

James M. Cain, Conceded by many writers and critics to be one of the most influential of America’s popular authors, is remembered primarily for his four controversial novels of the 1930s and ’40s — The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity, Serenade, and Mildred Pierce. However, Cain was essentially a writer of short fiction. This is confirmed when we recall that two of the above stories — Postman and Double Indemnity, which Ross Macdonald described as “a pair of American masterpieces — are really novellas, barely qualifying as full-length works of fiction. In fact, when Cain sent the manuscript of the story later published as The Postman Always Rings Twice to Alfred A. Knopf, the publisher maintained that at 35,000 words it was too short to qualify as a novel and refused, at first, to pay Cain the $500 advance called for under an option clause in an earlier contract. Double Indemnity, which has only 29,000 words, was first published as an eight-part serial in Liberty magazine, and Serenade has only 44,000 words. Even Cain’s two biggest hardcover sellers — Past All Dishonor and The Butterfly — are slim little books, more accurately described as novellas. (The Butterfly hardly looks like a conventional novel, even with the twelve-page “preface” Cain added, in part, to give it additional heft in the bookstores.) His longest novel, The Moth, published in 1948, never achieved the impact or the sales of his earlier shorter books, and in a letter to a friend Cain offered one explanation for the book’s limited success: “If you ask me, a simple tale, told briefly, is what most people really like.”

In addition to writing eighteen novels (six of which were originally written as magazine serials), Cain was a prolific producer of sketches and dialogues, as well as dozens of conventional short stories, seventeen of which were published. The short-story form appealed to Cain and, as he wrote in the introduction to For Men Only, an anthology of stories he edited in 1944, “In one respect... it is greatly superior to the novel, or at any rate, the American novel. It is one kind of fiction that need not, to please the American taste, deal with heroes. Our national curse, if so perfect a land can have such a thing, is the ‘sympathetic’ character... I take exception to this idealism, as the Duke of Wellington is said to have taken exception to a lady’s idealism when he told her: ‘Madam, the Battle of Waterloo was won by the worst set of blackguards ever assembled in one spot on this earth.’ The world’s greatest literature is peopled by thorough-going heels” — as are many of Cain’s stories.

Cain was born in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1892. When he was eleven, his family moved across the Chesapeake Bay to Chestertown, where his father became president of Washington College. Cain graduated from the college at the age of seventeen, after four miserable years in which he said he felt like a “midget among giants.” Then, at an age when most intellectual kids still are in college, Cain spent four years in Maryland and Washington, D.C., drifting from one job to another before finally deciding what he wanted to do with his life. That decision came one day in 1914, when he was sitting on a bench in Lafayette Park, across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House. He had abandoned his ambition to become an opera singer and had just quit a job selling records at Kann’s department store, when suddenly, from nowhere, he heard his own voice say: “You’re going to be a writer.”

It came to him, “just like that, out of the blue,” he later said. “I’ve thought about it a thousand times, trying to figure out why that voice said what it did — without success. There must have been something that had been gnawing at me from inside. But if there was, I have no recollection of it, nor did I have any realization that the decision I’d made wasn’t mine to make... [It] would not be settled by me, but by God.”

Having decided to become a writer, Cain was faced with the problems of what to write and how to support himself until he became an established author. He went back to Chestertown, where his family welcomed his decision. His father found him a job teaching English and grammar at the college, after which Jamie, as his family and everyone around the little college town called him, settled down to try his hand at his new trade. “In the afternoons,” he said, “I played the typewriter, on which I was becoming a virtuoso, writing short stories in secret, sending them off to magazines, and getting all of them back. In a year or more of trying, I didn’t make one sale, until the thing became ridiculous and I was horribly self-conscious about it, to the point where self-respect, if nothing else, demanded that I quit.”

So Cain abandoned the typewriter, temporarily discouraged and wondering whether he had the talent for fiction. But those early, drifting months had not been completely wasted. While teaching at the college, he became a walking encyclopedia of grammar and punctuation, which he always maintained was at the root of good writing. There are no copies of his early stories in existence, but we can assume he had taken the first step in developing the famous James M. Cain style. And the four years he had spent drifting around the Eastern Shore in a variety of jobs, even an aborted singing career, provided abundant material for his later stories.

What to do next? He decided that a newspaper career might be a good way for an aspiring writer to make a living, so in 1918 he went to work as a cub reporter for the Baltimore American, then later, the Sun. But his newspaper career ended even quicker than his fiction-writing career when America entered World War I and Cain soon found himself in France with the American Expeditionary Force. After seeing action in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, he built something of a reputation as an editor of the 79th Division newspaper, the Lorraine Cross.

Returning to the States, Cain spent three postwar years as a reporter for the Baltimore Sun, and soon he felt ready to resume his efforts to write fiction. He was sent down to West Virginia in 1922 to cover the treason trial of William Blizzard, a young man who had led an armed insurrection against the coal mine operators, and after the trial, encouraged by H. L. Mencken, who was also on the Sun, Cain took a three-month leave to go back to West Virginia and try to write a novel about life in the coal mining communities. He wrote three drafts, but threw them all in the wastebasket. “The last one,” he said, “I wouldn’t have written at all if I hadn’t squirmed at the idea of facing my friends with the news that my great American novel was a pipe dream.”

There are no copies of these early Cain efforts so we cannot assess Cain’s first attempt at a novel, but Cain did say later that part of the problem was his journalistic approach: “I was so preoccupied with background, authenticity and verisimilitude, that I had time for little else.” There were also questions of style and structure. “I didn’t seem to have the slightest idea where I was going with it,” he said, “or even which paragraph should follow which.” His people “faltered and stumbled.” They were homely characters, who spoke a “gnarled and grotesque jargon that didn’t seem quite adopted to long fiction; it seemed to me that after fifty pages of ain’ts, brungs, and fittens, the reader would want to throw the book at me.”

So once again, James M. Cain had failed to write successful fiction. However, his reporting of the treason trial for the Sun and articles he subsequently wrote about the coal mines for the Atlantic Monthly and the Nation attracted considerable attention in the literary community. H. L. Mencken was especially impressed, and the two men became good friends. Later, after Cain quit the Sun and joined the faculty of St. John’s College in Annapolis, as a professor of English and journalism, he began writing for Mencken’s new magazine, the American Mercury.

Читать дальше