“I assume so.” Adam used an expression that Thomas used often.

Then, without advance notice, Thomas closed his eyes, curled up, and fell asleep.

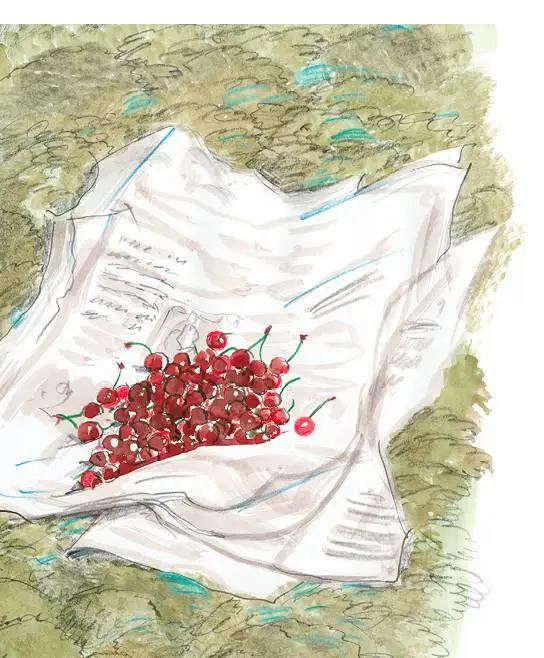

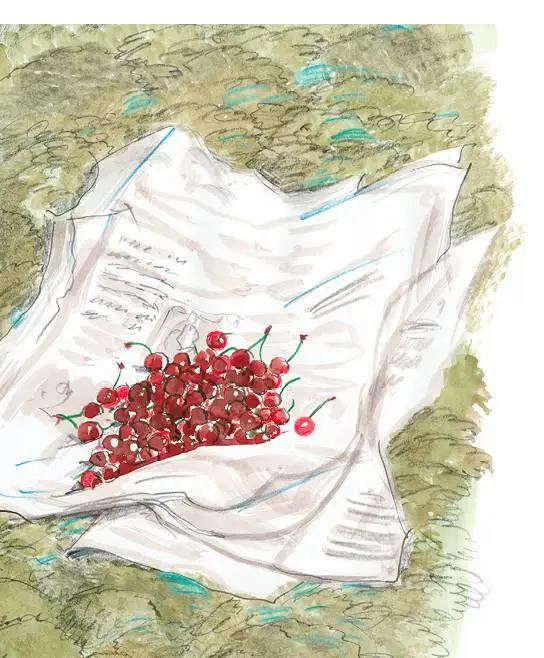

Adam watched him in his sleep and was surprised by the speed with which Thomas had passed from the world of wakefulness to the world of slumber. Adam wasn’t idle. He went out to see what else grew in the forest. He didn’t have to go far. Right next to them a cherry tree grew, and it was full of dark fruit. At first he wanted to wake up Thomas and show him the tree, but when he went back and saw how deep his sleep was, he let him be. He went back to the cherry tree, picked a handful, and returned to Thomas, amazed how well he was sleeping.

Thomas awoke in alarm.

“What’s the matter, Thomas?” Adam came to him. “I was late for school.”

“You had a bad dream. We don’t go to school anymore. We live in the forest.”

Adam showed him the cherries, and Thomas was enthusiastic. “What great cherries.” They sat and ate, enjoying the sweet taste of the black fruit.

“Where did you find the cherry tree?”

“Right nearby.”

“Adam, you have an unusual ability to discover things.”

“I love to find new things.”

“New things don’t come to me, because I’m nearsighted.”

You know how to sleep and dream, Adam wanted to say, but he didn’t, to avoid hurting his feelings.

Adam noticed that Thomas had stopped asking why his mother was late, but when evening fell, Thomas said softly, “Now the pupils in our class are at home doing homework. Only we two are abandoned in the forest.”

Adam sensed that the word “abandoned” was dripping with sorrow and yearning, so he asked, “Why did you say ‘abandoned’?”

“What should I have said? Do you have a better word?”

“We have been sent to learn directly from nature and to grow up.”

“Did our mothers bring us to the forest so we’d grow up?” asked Thomas in a tone that embarrassed Adam slightly.

“That idea just occurred to me now,” said Adam, laughing.

“As far as I know, you don’t start growing up at the age of nine,” said Thomas.

Then they went up to the nest.

“Our nest is well cushioned,” said Adam.

“True. It makes you want to sleep,” Thomas agreed.

The forest air and fatigue wrapped around the two boys, and they fell asleep.

Thomas dreamed that his mother was sitting on his bed and reading to him from Demian , a book by Hermann Hesse. His mother’s voice, before he fell asleep, was soft and calm, and the story appealed to him. Suddenly Thomas thought to ask his mother, “Why did you send me to the forest? Did you send me so I would grow up?” His mother was upset by his question. “I had no choice. I was afraid they would snatch you up.” “Where are they sending the children and the old people?” “Why do you ask?” “There are various rumors. When will the war be over?” “I don’t know. The moment it’s over, I’ll come and get you. You have to be patient.”

Thomas woke up very early, before sunrise. Adam was still asleep. The clear dream became even brighter, and he saw his mother before his eyes.

Adam woke up and asked, “Why aren’t you asleep?”

“I had a dream, and I guess it woke me up.”

“A good dream?”

“Mom promised she’ll come as soon as the war is over,” Thomas told him.

“When will the war be over?” Adam asked.

“She didn’t tell me in so many words. Dreams always hint, but they never explain.”

When they came down from the nest, a surprise awaited them. The white dog was standing near them on his tall, thin legs. Adam was glad and knelt down right away, stroking him and asking, “What’s your name, nice dog? My name is Adam, and I’m in the forest with my friend Thomas. I have a dog that I love in town. He’s smaller than you, and his name is Miro.”

The dog was astonished by Adam’s words and petting, and he stood still. It was hard to say whether he was a pet dog or a stray. His fur was smooth, and he wasn’t neglected. If he wasn’t neglected, that was a sign he was a pet. He has had enough to eat, the thought flashed through Adam’s mind.

Adam kept talking to him. He asked about his home, but because the dog didn’t respond, he asked, “Maybe you’re looking for a friend?” He didn’t respond to that question either. He became more and more mute, and Adam realized that the dog didn’t understand human language. The people he lived with didn’t talk to him and weren’t interested in him.

Thomas, who was standing at the side all the time, didn’t join in Adam’s efforts to get that pretty, thin creature to talk. He asked bashfully, “Can I touch him?”

“Of course. He came to visit both of us.”

Thomas drew close to the dog, stroked him, and said, “My name is Thomas.” Then he withdrew, pleased he had overcome his fear.

“Talk to him some more,” Adam encouraged him.

“What should I say to him?”

“Ask him where he came to us from.”

“It’s hard for me to talk to him. I’m not used to talking to dogs.”

“In a day or two you’ll learn how to talk to animals. It’s not hard.”

Adam patted the dog again. Filled with pleasure and trust, the dog sat down and closed its eyes.

“We’re going to be good friends,” Adam said, hugging the dog. The dog shook himself and stood up. Adam kept trying to talk him into staying. “We’ll love you and treat you well.”

The dog looked at him with his big eyes, and it was evident that his patience was wearing out. Adam took a sugar cube out of his pocket and brought it to the dog’s mouth. The dog smelled it and swallowed the sugar. Thomas and Adam stood tensely and watched the dog’s expressions. The dog stood there for a while and finally slipped out of Adam’s arms and went on his way.

Adam wanted to run after him, but when he saw that the dog was running hard, he called out, “Don’t forget to come back to visit us. We’re expecting you.” He waited for the dog to turn his head back to him, but when he didn’t, Adam stood still and followed him with his eyes as he went away.

The dog apparently knew its way and disappeared. Adam stood still, stunned.

“What’s the matter, Adam?” Thomas was alarmed.

“The dog left part of himself with us,” said Adam.

“I don’t understand you, Adam. You have to explain to me.”

“When animals go away, they leave part of themselves with you.”

“Do you really feel it, or are you imagining it?” “I feel it in my hand or my knees, and sometimes in my whole body.”

“Strange,” said Thomas. “Anyway, you spoke to the dog in a very natural way. How did you learn how to talk to dogs?”

“From Miro, our dog.”

“Do you talk to him the way you talked to the dog that came to visit us?”

“I talk to Miro like a friend.”

“Do you understand him, or does it just seem like it?”

“I understand him, and he understands me.” Adam didn’t get confused.

“Still, dogs aren’t in the human family.” Thomas spoke in his father’s voice.

“Miro is part of our family. Mom and Dad understand him even better than I do.”

Читать дальше