“Thank God,” said Adam’s mother in the doctor’s tone of voice.

All that day Adam and Thomas told about their life in the forest, about the raspberries and blueberries, about the brook, about the nest that protected them day and night, about Mina who had saved them from hunger, and about the old peasant who brought them bread and milk during the final hard days.

“I didn’t read, and I didn’t solve arithmetic exercises, but I kept a diary,” Thomas told his mother. “But it’s all broken up. We’ll only be able to tell about what happened to us in the forest for a few years.”

Thomas’s mother opened her eyes wide. Thomas’s words frightened her, and she said, “What do you mean by saying you won’t be able to tell about what happened to you in the forest for a few years?”

Thomas answered, “It’s hard to talk about fear and hunger. They are very concrete, but indescribable.”

When she heard his words, her eyes filled with tears.

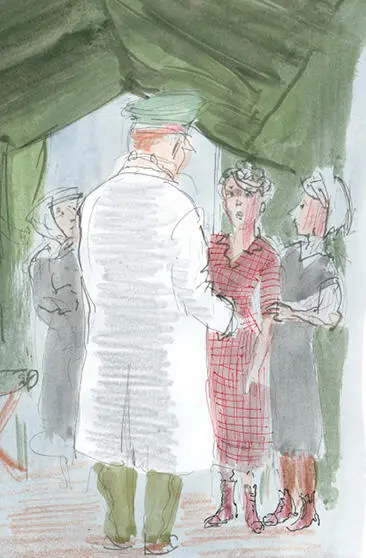

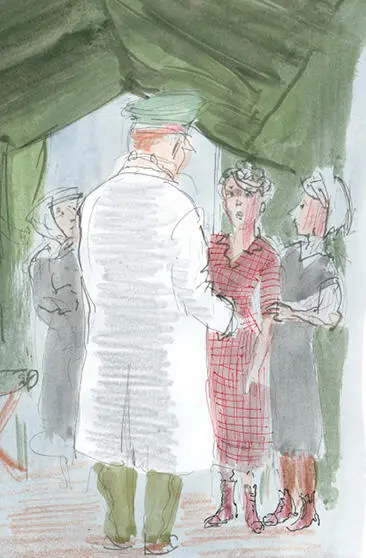

Meanwhile the doctor came out and said, “Come in and see our pretty little girl. She’s not only pretty, she’s also a heroine.”

Mina was lying in bed, her head raised on two pillows. Her eyes were open. Her beauty glowed from within her.

“How are you, Mina?” Adam’s mother asked, trembling all over.

After a short silence she answered, “Well.”

Adam’s mother didn’t ask any more questions.

“The medical team has fallen in love with Mina,” said the doctor, and his face filled with light.

They stayed in the infirmary tent for five days, constantly waiting in fear for the doctor’s announcements. The medic didn’t neglect them. He brought them soup, bread, and hard-boiled eggs. On the fifth day the doctor told them, “The girl is talking, asking questions and responding. She’s a girl from out of this world. You’ll have to keep bandaging her wounds. I’ll give you antiseptic and salve. The wounds are healing, but you mustn’t neglect treatment. The medical staff is impressed by Mina and wishes her a full recovery. You should know that she’s a miracle in every way. And you, where are you going?”

“We don’t know yet,” answered one of the mothers.

“We’ll give you some food to last for a few days.”

“Thank you, doctor. I can’t thank you enough.”

“We’re doing our duty as human beings. Tomorrow we’re moving from here. We’ve broken through the front. The German army is retreating in panic, but the way to victory is still long. I’ll give you a stretcher so you can carry Mina. She conquered all of our hearts.”

“How can we thank you, doctor?” Adam’s mother said, trying to restrain her tears.

“There’s no need to thank us. We’re here to do our duty.”

“You treated us with mercy. It’s been a long time since we saw mercy.”

“I’m just a doctor. You mustn’t attribute qualities to people that we attribute to God.”

“I’m sorry if I insulted you. I didn’t mean to,” she said, covering her face with both hands.

Thus they parted from the doctor who had saved them.

The sun came out from behind the clouds and lit up the snow. The snow absorbed the sun from above and glowed with thousands of points of light.

A military band played marches in the middle of the snowy forest. Thomas’s mother burst into tears, and Adam’s mother hugged her, saying, “Dear, thank God we found the boys. Now we have to take care of Mina. She needs a lot of attention.”

“Excuse me,” Thomas’s mother murmured and wiped her face.

The band continued to inspire joy.

Adam’s mother said, “Who watched over our children in this hard winter?”

“Our boys are smart. They took care of themselves,” said Thomas’s mother.

Adam wanted to ask how his father was, and how his grandparents were, but he blocked the words in his mouth. In his heart he knew it wasn’t the right time to ask. His mother sensed what was stirring in her son’s heart and said, “Let’s pray that Dad and your grandparents will return to us.”

Mina fell asleep on the stretcher, and the mothers wrapped her in the blanket.

First championed in the English language by Irving Howe and Philip Roth, Aharon Appelfeld was born in a village near Czernowitz, Bukovina, in 1932. During World War II, he was deported to a concentration camp in Transnistria, but escaped. He was eight years old. For the next three years, he wandered the forests. In 1944, he was picked up by the Red Army, served in field kitchens in Ukraine, then made his way to Italy. He reached Palestine in 1946. Today, Appelfield is professor emeritus of Hebrew literature at Ben-Gurion University at Beersheva, a member of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, and commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. He has won numerous prizes, including the Israel Prize, the MLA Commonwealth Award in Literature, the Prix Médicis étranger in France, the Premio Grinzane Cavour and Premio Boccaccio Internazionale, the Bertha von Suttner Award for Culture and Peace, and the 2012 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. In 2013, he was a finalist for the Man Booker International Prize.

Jeffrey M. Green began to translate for Aharon Appelfeld in the 1980s and has translated a dozen or so of his novels. Green is the author of Thinking Through Translation (University of Georgia Press), as well as short stories, poems, novels, book reviews, and essays.

Philippe Dumas is an an author and illustrator of dozens of books for children and adults. A graduate of the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, he divides his time between illustration and set design for the theater.

About Seven Stories Press

Seven Stories Press is an independent book publisher based in New York City. We publish works of the imagination by such writers as Nelson Algren, Russell Banks, Octavia E. Butler, Ani DiFranco, Assia Djebar, Ariel Dorfman, Coco Fusco, Barry Gifford, Martha Long, Luis Negrón, Hwang Sok-yong, Lee Stringer, and Kurt Vonnegut, to name a few, together with political titles by voices of conscience, including Subhankar Banerjee, the Boston Women’s Health Collective, Noam Chomsky, Angela Y. Davis, Human Rights Watch, Derrick Jensen, Ralph Nader, Loretta Napoleoni, Gary Null, Greg Palast, Project Censored, Barbara Seaman, Alice Walker, Gary Webb, and Howard Zinn, among many others. Seven Stories Press believes publishers have a special responsibility to defend free speech and human rights, and to celebrate the gifts of the human imagination, wherever we can. In 2012 we launched Triangle Square books for young readers with strong social justice and narrative components, telling personal stories of courage and commitment. For additional information, visit www.sevenstories.com.