A couple of scruffy types, perhaps clandestini, idled in the shade of the stoop as the Lulucitas emerged with their priest. But these were European, or as Euro as the golden-brown Romy. Perhaps a couple of Khazars, they might’ve been the beggars the police had stopped to check, earlier. In any case Barb knew what to do. She raised an open hand and, as she spoke her blessing, made sure they saw her lips move.

Also she dealt with her bodyguard. The young chowhound would’ve preferred to take the car, though it meant a roundabout of one-ways. Barbara had to insist, glancing up the stairs and thinking again of her mother-in-law, her trim flexibility. Here’s Neapolitan yoga, Aurora: the stairs. The security officer sighed mightily, combing the curls from his eyes with pudgy fingers. But the air on the hilltop wasn’t so heavy, so sulfur-rich, as down by DiPio’s clinic or Whitman’s studio. Besides, the gunman had Cesare to inspire him, a man in his seventies all but jogging uphill. The priest would wait for the other three at the top of each flight, his long face blazing with revival.

Barbara’s own face must’ve gone purple, because she kept talking. She filled Jay in on everything she’d learned that morning about the gypsy and the late Lieutenant Major; earlier, during the ride from DiPio’s to the Vomero, the husband had only gotten the shorthand. And more than that, the mother came to think she’d filled in a quake-wide gap in her own grasp on what had happened. As she climbed, she put it together, the news from her boys and the news from her priest. The two who’d come out of nowhere to gun down Silky Kahlberg — they must’ve been the two scippatori from the first day downtown.

“Romy was saying,” she huffed. “Guys from off the street.”

As the Jaybird took it in, he started climbing two stairs at a time.

“And a bandanna,” she went on. “Blue like the first day.”

“Guys felt guilty.”

“Felt contrition. Seeking absolution.”

“Plus Paul, hey. A holy child. To those two”

“Plus one was queer.”

This was only a guess based on a guess: the gypsy’s surmise about one of Silky’s killers. Nonetheless a gay clandestino would fit the scheme of things, as it was emerging there on the Vomero stairs. The aerobics hadn’t made Barb and Jay that dizzy. The husband got the connection, having sussed out the liaison’s sexual preference in his first week up at the Refugee Center. “See what he wanted. Nice boy-toy. Price of a pizza.” Jay understood that, for the former scippatori , the gaydar would’ve been part of the surveillance system. Part of tracking the family, seeking an opportunity to atone for what they’d done to the family, since the NATO man would’ve bragged to his sex partners (while of course giving away nothing they could use against him) about the systems he was jerking around.

“Silky’s boys,” Jay said. “They could’ve said something. Talked to our two guys.”

“This city. Always somebody talking.”

At last they reached the church, another Naples church with a cellar full of surprises. A person didn’t need to go downtown to find a Sotterraneo . The priest rushed on to the rectory but Jay and Barbara allowed themselves a breather in the narthex. Wonderful, the cool, the dim. The wife tugged at her armpits and the husband swabbed his neck as they eyed each other in a wheezing double-check of their sudden detective work. You think, Jaybird? Does it add up, Owl? Two homeless illegals had somehow first gotten a bike, then gotten lucky. Yet after that they’d suffered such pangs of remorse that eventually, in a perverted attempt to make amends, they’d committed murder. Their victim had been more of an inveterate bad guy than either of them, but nevertheless a figure of daunting status, an American officer.

The husky bodyguard came in off the church steps, with a melodramatic exhale. That and the petulant look he shot his two charges was enough to stop Barbara’s second-guessing. How far off the truth could she and her husband be? Anyway less than a month ago, outside these same weighty blonde doors, the police had snatched her. They’d snatched her and the children, and they’d taken their sweet time about letting her know what had happened to Jay. But neither then nor now had the authorities came anywhere near the real danger to the Lulucitas. Strangers had been privy to the moves they were making and the ways they were hurting, since the first blow to Jay’s head. For all Barbara knew, the blessing she’d given five minutes ago, the vagrants outside the palazzo, could’ve been another source of information for the family’s addled scippatori .

The mother turned and headed into the sanctuary. As soon as they reached the pews the bodyguard took a seat, sinking down and spreading out.

“Jay,” Barb growled as she marched on, “I’m angry. I’m still angry.”

“I hear that. Fucking can’t get past that first day. ‘Scuse me.”

Barbara, slowing down, gave him half a smile. She suggested, more gently, that they appeared to have figured out most of what had been going on.

The Jaybird nodded. “Next couple cases of pasta should about fill the truck.”

Beside the splintered altarpiece, the rectory door, they passed a crucifix. When Barbara paused to genuflect, the husband did the same, then ventured to guess that Cesare had some of the late Lieutenant Major’s counterfeits.

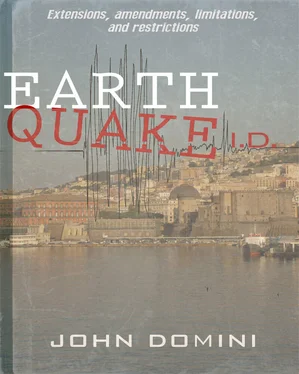

“The Earthquake I.D. He must’ve had some left over.”

The wife didn’t respond, surprised by the priest’s rooms. In Brooklyn and Bridgeport, the spaces behind the altar wall had looked more churchy, deep brown, a lot of oak. Cesare’s was mostly fungus-gray, steel-drab, as modern as the rest of the building. The old man stood at the desk, pulling open a drawer he hadn’t bothered to lock. First he brought out four or five vials of communion wine, the kind used for bedside visits, and these gave Barb a unexpected pang. Out of the blue she recalled the last time she’d seen her father. The grown Barbarella had spent an evening with fumble-mouthed old Dad, on his condo’s tiny deck in Vero Beach. They’d drunk the wine she’d picked up during the flight, the little bottles of red.

Then the priest brought out something else. Paper, that’s all: a sheaf of blank paper hardly pinkie-thick.

“The scippatori ,” he croaked, at last showing the effort of getting here.

Jay frowned. “What? I wasn’t carrying anything like this.”

For Cesare, raising his eyes seemed suddenly an enormous effort. His forehead crumpled; his grimace deepened. Barbara tried to look encouraging, she fingered her Madonna out from under her neckline, but she didn’t have a clue so far as the papers were concerned. The priest tapped a finger against the stuff, then as husband and wife bent over the desktop, he collapsed into his chair. The mother turned, worried; never mind the papers. She noticed how heavily the old man was sweating, the stains showing through his black cotton. He sprawled across the chair almost as feebly as he had (was it only an hour ago?) across Barbara’s sofa. By the time she could be sure that Cesare was breathing decently, Jay had begun to speak.

“It’s about the paper,” her husband was saying. “The paper itself .”

Barb felt crowded again, there between one man’s rickety splay and the other’s barrel build. The Jaybird held up two sheets of the stationery, a heavyweight bond. A specialty bond, with the roughage of an old scar, in which faint blue threads came together in a watermark.

“Are you saying….” Barb looked from the husband to the priest and back again. “Jay, those aren’t the I.D. There’s nothing—”

“They aren’t the I.D .,” Jay said. “There’s nothing there. This is about the paper.”

Читать дальше