John Domini

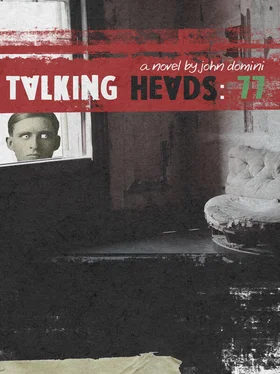

Talking Heads: 77

What a job you’ve got…, nothing to do but run from one dizzy amusement to another and then write a piece about it.

— Katherine Anne Porter, Pale Horse, Pale Rider

By Monday morning, Kit found it hard to believe the issue was nothing but paper. It was nothing but newsprint, finger-smudging and itch-inducing. The color of dead flesh. If he hadn’t scrolled it up into a stick, Kit wouldn’t even have known he had anything in his hand. Yet this weightless stuff, this imitation stick in his fist — this was his issue. This was Sea Level , Volume One, Number One. “A biweekly journal of politics & opinion.” Twenty pages staple-bound. Pub date January 6, 1978. Kit’s idea had become an office, and his talking to himself talking on the phone. Charter subscriptions were $15, and over the counter it cost 75 cents. It carried a trademarked title logo and his own name at the top of the masthead. Kit Viddich, Editor . Kit, not Christopher, another idea that had gone public. Another notion that seemed to need solidifying oomph.

For Sea Level was also a troublemaker. Volume One, Number One had hit the Boston streets at the beginning of the weekend, and by Monday morning it had stirred up some ruckus. It had whipped powerful people into rush meetings at the Massachusetts State House; it had carved out a clear agenda for Number Two. Hard to believe the issue was only paper.

Kit sat in his office, Sea Level scrolled in his hand, wondering. He was the only one there so far. The only one who’d heard the latest on the ruckus. And the first person he called was his wife.

“I heard from the State House again,” he said.

“Oh, not really. Already, Kit?”

“First thing when I came in.”

“And you mean to say it was the same sort of call? A call confirming what you heard Saturday?”

Hearing the good news repeated back to him made Kit wonder again about this paper in his fist.

“Bette,” he said, “it’s for real. There’s going to be an inspection.”

“Well, my. Are we proud?”

Kit touched his neck. He managed a laugh, a kind of laugh, a noise that went flat against the glass surrounding him. As Editor-in-Chief, Kit had wooden walls to hip level and glass the rest of the way.

“Are we, Kit?” his wife repeated. “Proud of our muckraking?”

He had a private booth, a saint’s reliquary. The others who worked for Sea Level —when they were in the office — had only the half-walls, in the old brownstone style. The ceilings were very high, American Empire, and Kit himself was built tall and elbowy, a ranch-bred Minnesotan. His laugh echoed a long way up. His wife went on waiting.

“Bet-te.” He drew out both syllables. “Actually, I believe that’s hard-nosed muckraking. Hard-nosed, darling. That’s the word.”

Winter static butterflied along the line.

“A man gets down in that muck with a soft nose,” Kit said, “he’s going nowhere.”

“Oh. Kit the wit.”

Kit the hurt, more like. The static didn’t improve, but he heard her sigh. “Betts, don’t tell me. The Apple’s giving you trouble again.”

“The Apple. Well, that plus a few of what I suppose you’d describe as crank calls.”

“Crank calls? What, heavy breathers?”

“Worse, I’m afraid. The sort who launch right into their erotic dreams.”

“You’ve had a few of these?” Kit frowned over the phone. “More than a couple?”

This time her sigh was exasperated. “Kit, didn’t you ask me about the Apple?”

Patience, husband. She doesn’t need you to tell her what to do about crank calls.

“Didn’t you ask me about that infernal contraption?”

Once Kit’s first issue had gone to the printers and he and Bette knew they’d have no unforeseen expenses, she’d bought a computer. She’d gotten one of the new in-the-home models. Kit’s wife worked in writing herself, editing papers for a couple of professors at Harvard Medical.

“Half the time,” she said, “well, you’ve heard of the worm in the Apple?”

Ah, Bette — like the actress. Like Bette Davis, another Concord Academy girl. By now Kit had some sense of how much star poses and stage business meant to them — how central it was to why they’d fallen for each other. Stage business had become, by now, their natural give and take. An arch intimacy. Freely they risked one-liners that would’ve had the other person groaning if they’d been spoken a second slower. It was a strange way to succeed as a couple, Kit understood, and it had more than a little to do with how his wife and he came to the marriage from such different directions. He was the hard-driving Minnesota investigator, and she the weary Brahman know-it-all. Kit understood; he could get his mind around all of this, more or less, even here in his office on a Monday morning. And even here, it had his heart growing baggy. In the center of his chest hung a big, gray beehive soaked with rain, sagging and heavy.

He could see her, too. Among the wisps of reflection in the glass wall before him, he could actually see his wife. At her new plastic keyboard, at the Cambridge end of the conversation, Bette had left her hair undone. Haystack hair. There were half-lit moments when she looked like another late-’70s California girl, another clone of Farrah Fawcett-Majors. To see her that way however was to overlook her mouth, her smile. Bette’s mouth contained more working parts than most. Sometimes when she smiled Kit thought of an antique wicker picnic hamper, all shelves and handles and drawers and flaps. That was her face, over her keyboard: a hamper in a haystack.

“Frankly,” she was saying, “I can see why you newsies stick to typewriters.”

Kit knew when to play the straight man. He pointed out that she’d taken a leap, getting the Apple. He couldn’t think of anyone else who had their own personal computer.

“Oh, come on. I’m not so much the brave pioneer as all that.” Bette mentioned a cousin who’d purchased one of the new machines, a man who did tax work and accounting. “At this rate,” she said, “the entire extended Steyes family should be online — isn’t that the word? The whole sick crew should be online by 1980.”

With that, at last, his wife congratulated him on today’s call. “You say this morning confirms it? A full-bore inspection? Well, my. Hard-nosed muckraking, indeed.”

“The Boston Building Commission.” With his free hand Kit stood his scrolled copy of Sea Level on his desktop, an exclamation point. “They had some kind of conference call Friday night, some kind of executive session. Quick and dirty, you know. And it’s on. They’re going to the penitentiary.”

Once more he jabbed the paper into the desktop. The lead article in Number One had been an examination of building decay in a state penitentiary, a prison named Monsod. The report had taken up more than half the book, its final columns unwinding on page 17. Kit had written the story himself. While Sea Level was getting underway he’d have to do a lot of that, writing the stories himself (ten o’clock on a Monday morning, and he still had the office to himself). On the penitentiary piece, Kit had done good work. He’d turned up more first-hand material than he’d have thought possible. He’d sent advance copies to State House committee people, and Saturday afternoon the first call had come. A contact at the Building Commission.

“My, yes,” Bette said. “The first story in the first issue of a shoestring venture, and the entire Massachusetts government springs into action.”

Читать дальше