We couldn’t say anything, only smile and raise our hand in farewell before climbing into the truck with Bon. The baby-faced guard raised the hatch and locked it. What? the commandant said, looking up at us. You still have nothing to say? In fact, we had many things to say, but not wanting to provoke the commandant into revoking our release, we only shook our head. Have it your way. You’ve confessed your errors and there’s nothing more to say after that, is there?

Nothing indeed! Nothing was truly unspeakable. As the truck departed in a cloud of red dust that made the baby-faced guard cough, we watched the commandant walk away and the Hmong scout, the philosophical medic, and the dark marine cover their eyes. Then we turned a corner and the camp disappeared from view. When we asked Bon about our other comrades, he told us that the Lao farmer had vanished in the river, trying to escape, while the darkest marine bled to death after a landmine sheared off his legs. At first we were quiet on hearing this news. What cause had they died for? For what reason had millions more died in our great war to unify our country and liberate ourselves, often through no choice of their own? Like them, we had sacrificed everything, but at least we still had a sense of humor. If one really thought about it, with just a little bit of distance, with even the faintest sense of irony, one could laugh at this joke played on us, those who had so willingly sacrificed ourselves and others. So we laughed and laughed and laughed, and when Bon looked at us as if we were crazy and asked what was the matter with us, we wiped the tears from our eyes and said, Nothing.

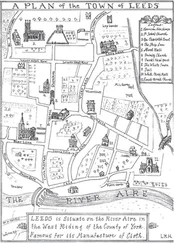

After a numbing two-day journey over mountain passes and crumbling highways, the Molotova deposited us on Saigon’s outskirts. From there we shuffled along sullied streets populated by sullen people toward the navigator’s house, our pace slowed by Bon’s limp. The muffled city was eerily muted, perhaps because the country was once again at war, or so we were told by the Molotova’s driver. Tired of the Khmer Rouge attacks on our western border, we had invaded and seized Cambodia. China, to punish us, had raided our northern border earlier in the year, sometime during my examination. So much for peace. What bothered us more was that we had not heard even one romantic song or snatch of pop music by the time we arrived at the home of the navigator, Bon’s cousin. Sidewalk cafés and transistor radios had always played such tunes, but over a dinner only marginally better than the commandant’s meal, the navigator confirmed what the commandant had implied. Yellow music was now banned, and only red, revolutionary music was allowed.

No yellow music in a land of so-called yellow people? Not having fought for this, we could not help but laugh. The navigator looked at us curiously. I’ve seen worse, he said. Two stints in reeducation and I’ve seen much worse. He had been reeducated for the crime of trying to escape the country by boat. On those previous attempts, he had not taken his family with him, hoping to brave the dangers alone and reach a foreign country from where he could send money home to help his family survive or flee, once the route was proven safe. But he was certain that a third capture would lead to reeducation in a northern camp, from which no one had so far returned. For this attempt, then, he was taking his wife, three sons and their families, two daughters and their families, and the families of three in-laws, the clan living or dying together on the open sea.

What are the odds? Bon asked the navigator, an experienced sailor of the old regime whose expertise Bon trusted. Fifty-fifty, the navigator said. I’ve only heard from half of those who fled. It’s safe to assume the other half never made it. Bon shrugged. Sounds good enough, he said. What do you think? This was addressed to us. We looked to the ceiling, where Sonny and the crapulent major lay flat on their backs, scaring away the geckos. In unison, as they were now wont to speak, they said, Those are excellent odds, as the chances of one ultimately dying are one hundred percent. Thus reassured, we turned back to Bon and the navigator and, with no more laughter, nodded our agreement. This they interpreted as a sign of progress.

Over the next two months, as we waited for our departure, we continued working on our manuscript. Despite the chronic shortages of almost every good and commodity, there was no shortage of paper, since everyone in the neighborhood was required to write confessions on a periodic basis. Even we, who had confessed so extensively, had to write these and submit them to the local cadres. They were exercises in fiction, for we had to find things to confess even though we had not done anything since our return to Saigon. Small things, like failing to display sufficient enthusiasm at a self-criticism session, were acceptable. But certainly nothing big, and we never failed to end a confession without writing that nothing was more precious than independence and freedom.

Now it is the evening before our departure. We have paid for Bon’s fare and our own with the commissar’s gold, hidden in my rucksack’s false bottom. The cipher that we share with the commissar has taken the gold’s place, the heaviest thing we will carry after this manuscript, our testament if not our will. We have nothing to leave to anyone except these words, our best attempt to represent ourselves against all those who sought to represent us. Tomorrow we will join those tens of thousands who have taken to the sea, refugees from a revolution. According to the navigator’s plan, on the afternoon of our departure tomorrow, from houses all over Saigon, families will leave as if on a short trip lasting less than a day. We will travel by bus to a village three hours south, where a ferryman waits by a riverbank, a conical hat shading his features. Can you take us to our uncle’s funeral? To this coded question, the coded answer: Your uncle was a great man. We, along with the navigator, his wife, and Bon, clamber on board the skiff, we carrying in our rucksack our rubber-bound cipher and this unbound manuscript, wrapped in watertight plastic. We glide across the river to a hamlet where the rest of the navigator’s clan will join us. The mother ship awaits further down the river, a fishing trawler for 150, almost all of whom will hide in the hold. It will be hot, warned the navigator. It reeks. Once the crew battens down the hatches of the hold, we will struggle to breathe, no vents to alleviate the pressure from 150 bodies locked into a space for a third that number. Heavier than depleted air, however, is the knowledge that even astronauts have a better chance of survival than we do.

Around our shoulders and chest we will strap the rucksack, cipher and manuscript inside. Whether we live or die, the weight of those words will hang on us. Only a few more need to be written by the light of this oil lamp. Having answered the commissar’s question, we find ourselves facing more questions, universal and timeless ones that never get tired. What do those who struggle against power do when they seize power? What does the revolutionary do when the revolution triumphs? Why do those who call for independence and freedom take away the independence and freedom of others? And is it sane or insane to believe, as so many around us apparently do, in nothing? We can only answer these questions for ourselves. Our life and our death have taught us always to sympathize with the undesirables among the undesirables. Thus magnetized by experience, our compass continually points toward those who suffer. Even now, we think of our suffering friend, our blood brother, the commissar, the faceless man, the one who spoke the unspeakable, sleeping his morphine dream, dreaming of an eternal sleep, or perhaps dreaming of nothing. As for us, how long it had taken us to stare at nothing until we saw something! Might this be what our mother felt? Did she look into herself and feel wonderstruck that where nothing had been something now existed, namely us? Where was the turning point when she began wanting us rather than not wanting us, seed of a father who should not have been a father? When did she stop thinking of herself and began to think of us?

Читать дальше