Ku reread the report, smoked a cigarette, and considered its contents. Then he threw the sheaf of papers into the glowing oven. He had to prevent the others from reading it, in part to protect his source, but also in part to preserve the ignorance that kept his troops disciplined. At all costs, he wanted to keep them from knowing that the attack on 181 Avenue Foch had been motivated in part by Ch’i’s death.

The report was stylistically and grammatically jumbled. It alternately paraphrased the poet and quoted him directly. A few paragraphs had been cautiously rewritten, but then the writer would lace the facts boldly with his own observations. Ku paid extra attention to inconsistencies. For instance, at one point the poet was quoted as saying that he thought Avenue Foch had been a revenge killing, but the very next paragraph had him saying that “the police are sure these people belong to an underground Communist organization.” Could it be that the poet and his superior had different opinions?

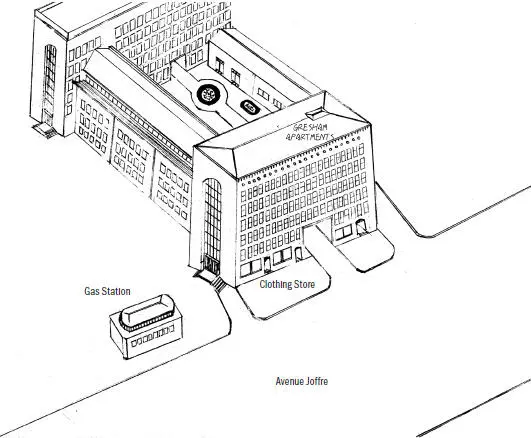

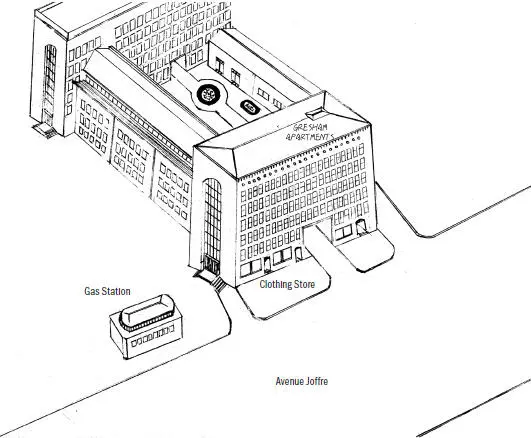

The safe house where Hsueh was taken to meet with Ku

Ku believed that precisely these inconsistencies made the manuscript reliable. They proved it consisted of casual conversations recounted by one person to another and then crudely summarized by Hsueh — no wonder they had lost some of their original shape. The value of this intelligence lay in the contradictions, Ku thought. They showed that the Concession Police was still in the dark about Ku’s true identity.

Before dinner, he summoned Leng and came down on her hard. She had broken the rules by making contact with a complete stranger at a crucial point of the operation, and to make matters worse, she had lied. Why claim that she and Hsueh were old acquaintances when they had only just met? Don’t be fooled by a petty bourgeois fling, he told her. And never, never think you can get away with lying to the Party. Only when Leng began to sob did he turn on his reassuring voice and praise her for winning Hsueh over to their side.

The more violent the struggle, the more unexpectedly love can appear, he said. It didn’t surprise him at all. He mentioned a few instances in which fellow comrades had gotten married in the face of the firing squad. Who knows, the two of you could have a pair of little revolutionary babies, he teased. When you’ve completed all the missions you’ve been given, you can move on to the Soviet Union, to Hong Kong, or to France. Isn’t Hsueh half French? He got a little caught up in his own speech until he noticed that Leng looked confused. Of course, once the revolution has succeeded in one country, the proletariat vanguard will have to export it to other countries in the grip of capitalist oppression. Maybe the two of you will have a part to play in the Communist revolution in France.

But after Leng left, he began to think about how difficult it was to maintain the focus of his team. These young people were as naïve as they were plucky, and up until now he had singlehandedly controlled what they thought. But he couldn’t guarantee that they would not waver. That was why they had to constantly be moving on to new targets. He felt defeated, somewhat lethargic — maybe the cigarettes were giving him a headache. He had never gotten over Ch’i’s death.

He called the safe house on Boulevard des Deux Républiques. Most of Lin’s unit was with him at the moment; he had summoned them for this operation. Lin himself had been ordered to wait in the apartment, but no one was answering the phone. Time to plan a new operation, he thought.

The cell was growing. There were three units under his command, all fully equipped. He had an eight-cylinder French-made car. And if he wanted another one, the steady stream of operations was bringing in plenty of cash. He even had a reliable police source. He had established himself in the Concession.

After the operation at 181 Avenue Foch, one of those fixers who seemed to know everyone and have complicated allegiances brought him a message. The Boss was offering him 100,000 silver yuan for a truce. Ku hadn’t responded yet. The Green Gang was treating his group as one of those brash new outfits trying to make a name for itself by perpetrating a series of killings, but Ku wanted more. He wanted a revolution that would alter the balance of power in the Concession.

The dark bricks of the building outside reflected the glow of the late afternoon sun. A foreign woman with auburn hair opened the window, through which piano music sounded faintly, in fits and starts, as though the Victrola was spinning erratically. There was a bitter taste in his mouth. Too many cigarettes. He was getting hungry. He came into the living room for dinner.

“All the papers called him a public menace,” Hsueh was saying. He was telling a tall tale while Leng picked listlessly at her food. Park was trying to find the holes in Hsueh’s story:

“That’s impossible. It can’t be done. You’ve never been in a gunfight. Americans love to exaggerate — you can’t just drive through a barricade like that, bursting through crossfire.”

“Why not? As long as your engine’s powerful enough and running fast?”

Hsueh stopped talking as soon as Ku came into the room. Hsueh is telling a story about an American outlaw robbing a bank, when all I want to do is have dinner, said Park.

“Really, the president of the United States nicknamed him the enemy of the people. Think about it. Banks are the heart of the capitalist system.” Hsueh sounded ridiculous when he tried to use Communist jargon. He might get the words right, but they all came out sounding wrong.

Ku had considered robbing a bank, but he wasn’t sure the cell was ready for an operation on that scale.

He wouldn’t want to target a bank branch that was either too small or too big. The biggest branches had scores of guards and direct phone lines to the police station. They were all in the busy heart of the Concession, where police armored vehicles could reach them within minutes. As Park had pointed out, there was no way to burst through a barricade on a big street.

No, he didn’t need tall tales. He needed intelligence, real intelligence. He wanted to sit down properly with Hsueh, get a piece of paper, and list everything he needed to know. He would give Hsueh some tips on the right questions to ask the next time he got a drink with his poet friend.

All kinds of questions occurred to him right away. Inspired by Hsueh’s story, he wanted to know how many policemen there were and how their armored vehicles were fitted out. Of course, he also wanted to know more about that Inspector Maron who was after him.

Putting himself in Hsueh’s shoes, he wondered whether the poet would smell a rat. An ordinary photojournalist at a French paper, asking all these questions about the cops? How could he work them into the conversation without raising suspicions? He would have to coach Hsueh not to ask them all at once. Ask a question in the pause between two toasts. If the poet is quiet, if he looks uncomfortable or tries to change the subject, then act like you were just wondering out loud, as if no one asked and you’re not interested in the answer, and never mention it again.

He brought Hsueh to the room where they had originally met. Now they were sitting on the same side of the horseshoe-shaped table. He took out a pen and paper, like a tutor talking to a student. More questions came to mind. Hsueh mentioned the lieutenant in charge, the man from the Political Section. According to Hsueh, the poet had once said that this lieutenant thought Ku’s cell was nothing to worry about. It was a “little red flea”—Hsueh hesitated perceptibly before saying the words — that would amount to nothing. Ku didn’t lose his temper. He simply asked more questions about the lieutenant.

Читать дальше