“Are you ready?” she asked.

“This dragonfly is beating itself against the window,” I said.

She looked at it blankly.

“I think it’s going to die,” I explained.

“Then we should do it in another room, I guess?” she said.

I stood there looking at the window and then at the food in my hands. The orange was sweating condensation from the refrigerator. Oranges “breathe” even after they are picked. Torn from their branch, they continue to take in oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide through their skin like small, hard, naked lungs.

“I don’t feel very well,” I said.

B looked at me and then she sat down. She seemed to collapse slightly as I watched her, her shoulders slouching forward, caving her chest.

“Look,” she said. “I know it’s not going to look perfect. I’m not going to be mad at you if it doesn’t look right or if I don’t look exactly the way you look. I know it’s not easy to do things with my face. I know that I have weird proportions, and a big nose, and a big forehead. It’s irreparable. That’s why I’ve always been so scared of putting makeup on, that I’d do all that work and end up looking like myself, exactly like myself but with things smeared on me. I just want to try it this once and I don’t know how to do it myself. I’ll probably look awful,” she said.

She was rubbing her thumb hard against the side of the cup like someone trying to rub the prints off her own fingertips.

If you were a person, you were supposed to want to be a better person. Better people had a surplus of themselves that they were willing to give away, something they could separate out and detach. In me the portions only separated, pulling apart and waiting there for something to happen. I could see what it was that I could give B, but I couldn’t really give it. In fact, I wanted to keep it for myself, to take it and run. All around me, people were giving feelings and help to one another all the time, as if it were the only thing to do. And I watched these exchanges like a dead thing, a thing sealed off perfectly, a room with no holes in or out.

“You’ll look great,” I said. The light from the living room lamps felt warm and prickly next to me. “You look great,” I said.

She seemed like she wanted to smile. Her face bunched and crinkled around the eyes. I looked back at the window where the screen sat open to the night air, and I saw nothing, heard nothing.

THE MIRROR IN MY BEDROOMshowed the two of us side by side. All I said was that I didn’t want to talk. “I don’t want to get distracted,” I said, and she nodded the way I was sure she would have nodded to anything I said then — worried, but with some potential for happiness hidden within. I did the foundation for her skin, which was the same color as mine. It was a color called bisque, the word for clay in its first stage of firing, hard, dry, unglazed, unfinished. It was also the word for a kind of soup made from the roasted husks of things. The makeup changed the face without changing it at all, it seemed only to restore to it an evenness that it had always held underneath, an even surface without pock or worry. The better person hidden inside the real person.

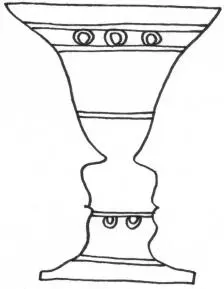

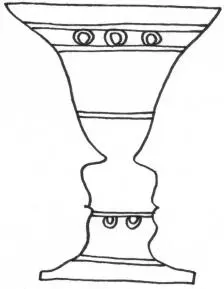

I wanted to be gone, to be by myself, to be with C, but instead I held still and reminded myself that this impression of uncovering a face was exactly as real as the fact that I was covering up a face at the same time. It was like the optical illusion where you see the vase and the two faces in the same image, but you can’t see them both at once.

The single image splits into two, which occupy the same space without sharing it. Or maybe it’s the opposite: the two objects find themselves in shared space, and the thought of one after the other in the mind of the viewer’s eye, vase face vase face vase face vase face, makes them grow together. The two words even begin to sound alike, like the same words spoken in the mouths of two people from different, distant places. I poured makeup on a white foam sponge so that it looked like a little puddle of skin suspended on nothingness, and then I dabbed it against her cheek over and over again. I dabbed it against her cheek, and then I did smooth, long strokes. I left skin-colored streaks that vanished a little more with every stroke. She was disappearing, or reappearing, or appearing for the first time, whatever.

I had covered all the spots, and now, when I looked at it, her face had the texture of a piece of pottery. I saw pores only when I leaned in close to the nose, where they appeared as tiny skin-colored mounds rising out of little sloping craters. People were such fragile things: they existed only from a certain angle, at a certain scale and spacing. Forget where to stand and you’d lose them completely. From this distance she didn’t resemble me much, though she didn’t exactly resemble herself, either. I rubbed at the edge of her jaw to blend the makeup. Then I did the lips. I used the things I had around, without wiping them off: my own lip balm, gooey and flavored like an orange Creamsicle, a lipstick that I wore a lot and had worn down to a flat, wet-sheened plateau with half a rim on it. I dabbed the color on with my fingertip, the padded part, poking at her lower lip and watching it spring back up. It was just like painting a portrait of myself, I thought, onto the face of another person.

I remembered one summer that I spent at my aunt’s house when I was younger, middle school, maybe. My aunt spent most of her day doing embroidery while her husband was at work, sitting in front of the TV and watching movies on mute. The movies were action films, thrillers, things that she and my uncle had originally bought for their son to watch. She didn’t pay much attention to the story line; the movies were a type of home decor, a device casting light and movement. I would walk through the living room on the way to somewhere else and see the warm yellow glow of an on-screen explosion playing off her smooth, serene face.

One of the movies she put on involved two men who were hardly ever pictured in the same frame. One was squarish and broad, the other angular and hawklike. The squarish man was seen in an office and then in a sort of hospital room. The angular man was pacing around a tarmac. Then the angular man was waking up and walking around. Then the square-jawed man was waking up. They both seemed to chase something, separately, using many different kinds of vehicles — planes, cars, boats. I understood it as some sort of story where two men competed to be the first to capture some unspecified thing they both wanted. Years later, C told me that it was actually a movie about identity theft. One of the men had swapped appearances with the other, then the other swapped appearances with the first. Then they worked to undo each other. C said that I should have picked up on the identity swap by noticing that the square man’s body language was initially heroic and then became sneaky and aggressive, while the angular man’s body language began sneaky and turned heroic. I told him that it would be nice if we could all think that way, but in actual life we were supposed to recognize a person in spite of their mannerisms rather than because of them. We were supposed to trust the similarity of their face in the moment to the face we remembered. “Otherwise,” I said, “I would treat you like a stranger every time your mood changed.” C had just looked at me for a while, seeming confused, not saying anything at all.

I held B’s smallish face in my hands and I gripped her chin a little harder than I had to because I could get away with it, I was making her so happy right now. Before there were mirrors or cameras to allow you to face yourself, you had to see yourself through other people. I tried to think that I was painting a picture of my face on hers so that I could see myself better. See myself filled out rather than flattened, see myself as C saw me. I wasn’t losing anything or giving myself away, I was just expanding, becoming more, many, like the television image and its occupation of all those otherwise empty screens. The image I thought of as mine sitting on the surface of her skin would absorb her to me and I might know what it was like to be myself outside of myself, for once. To see a part of myself that I could observe and recognize, but which transmitted no feelings. A numbed-out limb that could do what it did without me.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)