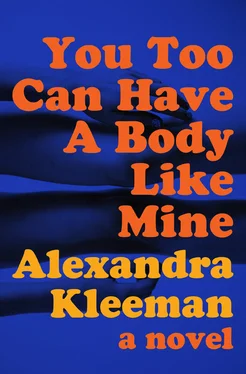

Alexandra Kleeman

You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine

It could be said that the orchid imitates the wasp, reproducing its image in a signifying fashion (mimesis, mimicry, lure, etc.). . At the same time, something else entirely is going on: not imitation at all but a capture of code, surplus value of code, an increase in valence, a veritable becoming, a becoming-wasp of the orchid and a becoming-orchid of the wasp.

— DELEUZE AND GUATTARI, A THOUSAND PLATEAUS

Blessed is the lion that the human being will devour so that the lion becomes human. And cursed is the human being that the lion devours; and the lion will become human.

— THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO THOMAS

IS IT TRUE THAT WEare more or less the same on the inside? I don’t mean psychologically. I’m thinking of the vital organs, the stomach, heart, lungs, liver: of their placement and function, and the way that a surgeon making the cut thinks not of my body in particular but of a general body, depicted in cross section on some page of a medical school textbook. The heart from my body could be lifted and placed in yours, and this portion of myself that I had incubated would live on, pushing foreign blood through foreign channels. In the right container, it might never know the difference. At night I lie in bed and, though I can’t touch it or hold it in my hand, I feel my heart moving inside me, too small to fill the chest of an adult man, too large for the chest of a child. There was a newspaper article about a man in Russia who had been coughing up blood; an X-ray showed a mass in his chest with a spreading shape, rag edged. They thought it was cancer, but when they opened him up they found a six-inch fir tree embedded in his left lung.

Inside a body there is no light. A massed wetness pressing in on itself, shapes thrust against each other with no sense of where they are. They break in the crowding, come unmade. You put your hand to your stomach and press into the softness, trying to listen with your fingers for what’s gone wrong. Anything could be inside.

It’s no surprise, then, that we care most for our surfaces: they alone distinguish us from one another and are so fragile, the thickness of paper.

I WAS STANDING IN MYroom in front of the mirror, peeling an orange. I cradled its exact weight in my palm, sinking a nail through the topmost layer. I dug a finger under its skin until I felt cool flesh, then I rooted that finger around and around. The rind tore with a soft, cottony sound, the peel one smooth, blunt piece trailing off the fist of the fruit. I slipped my contacts in and blinked at the mirror. Most mornings I barely resembled myself: it was like waking up with a stranger. When I caught a glimpse of my body, tangled and pale, it felt as if there were an intruder in my room. But as I dressed and put on makeup, touched the little tinted liquids to my skin and watched the hand in the mirror move alongside my own, I rebuilt my connection to the face that I took outside and pointed at those around me. My hand ripped a wad of pulp and pushed it through the space between my lips. Juice crawled down the side of my palm. Like the moon, my mouth in the mirror seemed to look a little bit different each day. It was summer, and the heat hadn’t yet tightened around our bodies, making us sticky and moist, trapping us in a suit we hated to wear.

A breeze pushed through the open window, smelling of cut grass, chopped flowers, and I could hear the people outside leaving their homes. Their car doors opened and closed, tires shifting gravel as they pulled out of their driveways and vanished for eight or nine hours, only to return less crisp, their unbuttoned cuffs hanging open. I liked letting noise from the neighborhood leak into my sleep and begin turning things real. I liked it, except when I hated it, hated how close the houses were to each another, hated that the first outdoor thing I sighted each morning was my landlady’s swollen face as she poked her head out the door to grab the newspaper. She lived below us, but from certain angles she could see straight up into our unit. Every day she bent down to retrieve it, then turned around, craning her neck to peer in through my bedroom window, checking to see if I’d spent the night in my room. Her aggressively changing hairstyle, auburn one week and then a dirty highlighted blond the next, made it unclear whether she wore real hair or wore a wig, and if it was a wig whether she slept with it on. My roommate B said it was like she was a fugitive inside her own home, someone living on the run without going anywhere at all.

In the house next door lived a couple of college kids who kept the TV on at all times, even when they left for their classes or jobs or whatever responsibilities they had. Their screen glowed through the night, casting blue light on an empty couch. It went dark only when the kids were in that third bedroom, the one I couldn’t see from our apartment. Sometimes for variety B and I watched the TV in their house instead of the TV in ours, though at that distance we could only guess at what we were seeing, flipping through the channels on our end to find a match.

Across the street there was a family with a dog that slept most of the day, but a few times each afternoon it ran to throw itself at the front windows, smashing its muzzle against the glass and barking until the sounds it made warped and hoarsened. I’d get up from my desk to see what was wrong, but there was never anything to see, not even a squirrel. Sometimes then our eyes would meet, the dog and me, and we’d just stare at each other from across that street, not knowing what to do.

It was a safe neighborhood. There was nothing you could complain about without sounding crazy. The sun was bright outside and I heard birds hidden in the trees, swarming the bushes with sounds of movement, calling out, bending small branches beneath the weight of their small bodies.

THUMPING SOUNDS CAME FROM THEother side of the bedroom door. It was B moving around our apartment: one small thump from the living room, and another, and then the sound of something being dragged across the floor. I heard her going to start the coffeemaker and then giving up, opening the refrigerator and giving that up, too. Standing still in the middle of my room, I tried to gauge how much I could move without letting her know that I was live. She couldn’t assume that I’d be conscious this early in the morning, but that wouldn’t stop her from checking every five or ten minutes, pausing to listen for the sounds of someone wakeful. Then sometimes she’d sit herself near the door, ear against the doorjamb, and talk toward me as though we were having a normal conversation. She’d talk toward me until I responded. B said the apartment was lonely when I wasn’t awake. She said if I was sleeping, I was as good as dead. She meant in terms of companionship, interactivity, my ability to help her make breakfast for herself. When B did eat, which was not always, she preferred to touch the food as little as possible to keep her hands clear of what she called “that edible smell.” She needed my hands to cut, to squeeze, to handle, to break eggs and toss their slimy shells into the garbage.

B and I were both petite, pale, and prone to sunburn. We had dark hair, pointy chins, and skinny wrists; we wore size six shoes. If you reduced each of us to a list of adjectives, we’d come out nearly equivalent. My boyfriend, C, said this was why I liked her so much, why we spent so much time together. C said that all I wanted in a person was another iteration of my person, legible to me as I would be to myself. When he said this it felt like he was calling me lazy. B and I looked alike, talked alike, that was fair enough. To strangers viewing us from a distance as we wove a confused path through the supermarket hand in hand, we might seem like the same person. But I was on the inside and I saw differences everywhere, even if they were only differences of scale. We looked young, but there was a lost, childish quality to how she slumped over whatever she was doing. We had the same brown eyes, but hers were set deeper in her skull, pushed back so that they disappeared beneath the shadow of her brow. We were thin, but B was catastrophically so: I had helped her zip up a dress, I had held her hair back and rubbed the cool, clammy base of her neck with my fingers as she deposited the contents of her stomach into the sink. I knew how her bones looked and how they felt shifting just below the skin.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)