An abuse, of course, but perfidious, outrageous, and arbitrary to boot. Also, he went on to pardon the loser: Acquaintances of the man claimed he was actually a Bourbon and had only feigned loyalty to Little Philip. (There’s something that now might seem laughable in this. For seasoned gamblers like the Barcelonans, honesty in the game was sacred. What really infuriated them wasn’t Pópuli’s tyrannical cruelty but that he hadn’t hanged the loser.) But this was only a small, if macabre, side story. His truly atrocious act was to hang every single prisoner taken after a skirmish near Torredembarra. Two hundred prisoners, that is.

In this, he followed Madrid’s logic. The ministers there, after the Allied withdrawal from Spain, said that anyone opposing Bourbon forces was to be considered a rebel and treated accordingly. The view from Barcelona was obviously quite different. With the foreign troops gone, the Generalitat had hurriedly formed an army, paid for out of its own coffers. So they had regulars at their disposal, uniformed and on the Catalan government’s payroll. The spiral of reprisal and counter-reprisal between Bourbon and Miquelet — we’ve covered that. But for Pópuli to do that to two hundred men at a stroke was beyond atrocious. Two hundred regulars hanged! Don Antonio sent a missive to Pópuli asking if he’d drunk away his senses. Pópuli answered by saying the same treatment would be meted out to any prisoners taken from that day hence. Don Antonio was especially offended that Pópuli addressed him as the “Rebel Chief.” Don Antonio, a career soldier, and the most respectful gentleman when it came to the courtesies and conventions in war! This time Don Antonio replied, very well, he was then obliged to accord the same treatment to any prisoner taken by his side.

The men hanged from the city walls, in sight of the enemy encampment, comprised his answer. A dismal sight if ever there was one: below, the sharpened stakes of the palisade; above, the hanged men.

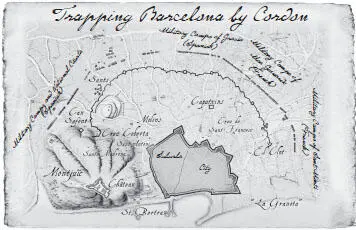

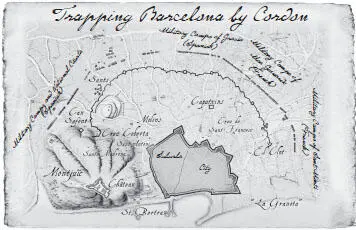

This opening exchange was more than enough to warn Pópuli’s army to take precautions. The regiments installed themselves two thousand yards from the city walls, just out of range of the artillery. They immediately began building a cordon, an enormous circuit of parapets to surround the entire city, blocking it off between the River Llobregat to the south and the River Besòs to the north — the idea being to isolate the city until the engineers had planned their line of attack.

A military cordon, in and of itself, is no great secret. A hastily dug ditch, basically, along which barricades are thrown up with compacted earth, planks of wood, stones, sticks, and anything else the besiegers can lay their hands on. They put any unevenness in the land to their advantage, making extra obstacles out of hummocks or natural ditches. As far as possible, they create scaled-down versions of the five-sided bastions. Needless to say, the besiegers will flatten any buildings in the vicinity, no matter how small, for matériel.

The building of the cordon was under way when three messengers arrived bearing Pópuli’s surrender ultimatum. The mood in the city was such that these were more likely to be strung up than welcomed — a double guard, bayonets drawn, had to form to protect the men from the baying crowd.

That night Don Antonio called me in to see him. As soon as I came into his study, he addressed me: “I want you to go with the emissaries bearing the reply.”

“Me, Don Antonio?”

“You’re my aide-de-camp, if memory serves. And this is precisely the kind of occasion when aides-de-camp come into play. It isn’t only the city’s honor that’s at stake here but, since I am commander of the garrison, mine, too.”

“Certainly, Don Antonio.”

“I already know you’re not a soldier, just an engineer in uniform, and the most basic rudiments of militariness are quite beyond you. But do you think you could be so kind as to address me as ‘General’?”

“Yes, General.”

“I need to know you won’t be discourteous in any way with the enemy. Their army has just pitched, and in war, appearances are as important as in matters of the heart.”

“You’re right, Don Antonio.”

“They’re constantly labeling us seditious, countryless, kingless, and dishonorable. What better way of refuting such charges than to be courteous with them, with their troops looking on? You mustn’t let anyone spoil this. Graciousness, good deeds, gentlemanliness, gallantry, neatness. This is your task.”

“As you wish, Don Antonio.”

Honestly, it seemed like a waste of time to me. The Bourbons were in place, they were here for our blood; no amount of talking was going to change that. But that was the way with military honor in my time: a bloodbath with spotless manners.

A young Pelt was charged with taking the city’s answer to Pópuli. Evidently from a good family, he appeared proud to have been given the job, and had dressed in his best attire. He received me with a smile. “I’m told you’ll be acting as my second,” he said. “Do you know the protocol?”

“Well, no.”

“I go first. You stay to my right, a pace behind. After you, the Bourbon messenger, and bringing up the rear, two standard-bearers, one with the royal standard, the other with parliament’s. Be sure to adhere to the conventions.”

“As you wish.”

“We’ll bow to their officers — amicably but never submissively. Remember, we’re at war!”

He was the one, it seemed to me, who had forgotten we were at war.

“And when exactly,” I said, “does bowing go from being amicable to submissive?”

“Don’t worry about that. All you have to do is, once we get there, hand me the missive. I unroll it, and I read it out.” This little Pelt was indeed proud to be leading the delegation. “I haven’t slept all night,” he said, beaming. “I’ve been working on memorizing a few immortal words to add to the government’s missive. Today, sir, we shall make history.”

The location of the Bourbon encampment, just out of range of the city’s artillery, meant it was quite a walk to get there. For my part, I was deep in thought the whole way, and not altogether happy thoughts.

We halted very close to their front line. There were thousands of soldiers working away on their ditches and barricades, all the way from Montjuïc to the mouth of the River Besòs. As far as the eye could see, men were chest-deep and shifting shovelfuls of earth.

The dimensions of the ditch, the sight of so many thousands of men working so systematically, intelligently, to bring about our destruction, left me feeling stricken. I’d been on the other side in Tortosa, so I hadn’t comprehended how distressing this all was from the point of view of the besieged.

A few minutes later, a podgy colonel came out to meet us, with four officers alongside. Coming a little way past the half-finished trench, this colonel addressed us brusquely: “You took your time.”

All the buggering about preparing for ceremony, and the Bourbons didn’t even bother to greet us.

“The reason for our lateness,” I said, stepping to the front, “is explained in the first paragraph. Here, read it for yourself.” I handed over the missive, somehow forgetting the protocol, and the Pelt’s immortal words.

The colonel, seeing that it was written in Catalan, thrust it back into my hands. “Tell us what it says in Castilian!”

The colonel and the men he had with him seemed cast from the same mold: dark eyes, pompous-looking mustaches, and a studied haughtiness to them all. I took a breath. There are a thousand ways to offend one’s enemy — now that I was going to have to read, I chose to do it in a chirpy tone, enunciating slowly as though reading to the village idiot — as if I doubted his ability to comprehend the civic composure of the people of Barcelona.

Читать дальше