There were disgraceful scenes. Don Antonio in a council of war with the Red Pelts, screaming his head off — flushed with rage — demanding, protesting, that they allow him a hundred men? Even fifty? Pitiful. A commander in chief being denied the right to move a handful of cripples. All we needed at that point was for Villarroel’s aide-de-camp to be one Martí Zuviría, a fellow universally known for his diplomacy. More than once — and more than twice — I nearly smashed in some councilor’s spectacles. It was infuriating. More than infuriating, because in certain situations, stupidity can come to resemble pure treason.

Let us recall that when it all began, in that ominous summer of 1713, the enemy was approaching Barcelona at a forced march. The Allies’ garrisons were handing the keys to our cities to the killer. Deceived, disconcerted, with no authority giving them orders and all taken completely by surprise, it had never occurred to the Miquelets scattered around the countryside that such a stab in the back was possible. They came down from the mountains and, from one day to the next, found friendly sites occupied by Bourbon troops. There was nothing they could do but remain on the horizon watching the fires, the looting, the executions. The final uproar.

In those circumstances, some drastic decisions were essential: extending the Crida right across the country, proclaiming the legitimacy of Barcelona’s government, and bringing together disparate fighters under a single banner. They had to prevent more towns and cities from falling into Bourbon hands. And for this, it was inescapable, desperately urgent, to show some symbol that would unite those who were longing for a voice to lead them. Villarroel ordered a military delegate to leave the city immediately with the silver mace and the banner of Saint Eulalia and travel across the country proclaiming that the struggle was not over.

“Take the sacred banner of Saint Eulalia beyond the Barcelona walls?” The Red Pelts were not sure. “That is most unusual. This will require a debate first.”

They weren’t joking! Solemnly, they gathered in council. Was it fair and fitting within the law and tradition that the sacred banner should be taken outside Barcelona’s walls? What honorable escort would accompany it? As for the few noblemen who were still in the city, were their titles sufficiently worthy for them to carry the pole and its braids? The debate stretched on; it was resumed the following day and then the next, and the next, without arriving at a definitive legal conclusion. Villarroel was absolutely incensed. By the time they had decided, the enemy would have taken control of all of Catalonia, with the exception of Barcelona and a few isolated sites like Cardona, those places where the most determined native commanders had refused to comply with the imperial orders.

Let us now examine the fortifications of Barcelona, which so often used to make me turn away, unwilling to judge them so as not to relive my past as a student in Bazoches.

The first order Villarroel gave me, his first commission, was to produce a report on the general condition of the defenses. I obeyed. I walked around the whole site. I cried. And when I say that, I am not, to my shame, speaking rhetorically.

As well as being an engineer, I happened also to be a Barcelonan. And when you examine the walls of your own city, knowing with certainty that they are going to be attacked by armed men ready to burn down your house, kill your children, and rape your wife, you see things somewhat differently. According to le Mystère , I ought not to feel emotion. A Maganon without a cool head is not a Maganon or anything at all. To justify my dismay, however, I should tell you that what I found was a complete and utter disaster.

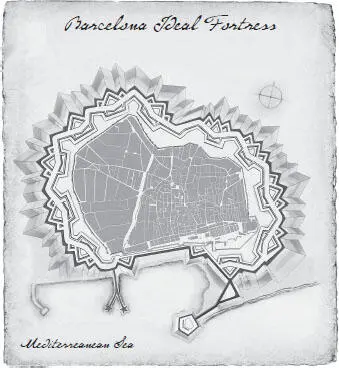

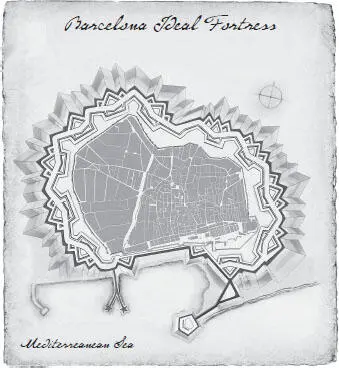

Comparisons can be useful. Look at the next illustration. Put it in the place where it’s supposed to go, or you can forget that you and I ever met, you fat old magpie.

If by any chance, destiny had seen good old Zuvi commissioned to fortify Barcelona, this would have been the optimal result.

As you can see, the city walls and the inner bastions are protected by a series of staggered half-moons or ravelins, perfectly arranged and three meters deep. Each one would have to be taken in separate attacks, without this ever affecting the main line of defense. By the time Jimmy managed to reach our final redoubt, the number of his dead would form such a tall mountain that the top ones could be buried on the moon. In fact, and following Vauban to the letter, the very existence of such fortifications would discourage any assault. Jimmy was a sly fox and would have graciously declined the honor of leading a siege of such complexity. And if not Jimmy, who else could vanquish us?

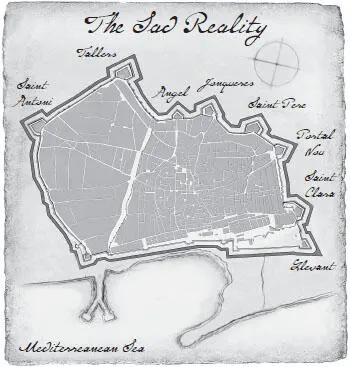

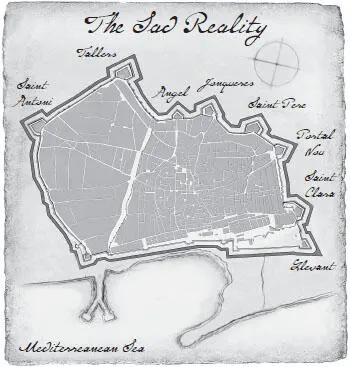

Now compare the previous plate with the sad reality, on the following page.

Devastating. Incongruous. Dislocated jaws, a heap of shapeless lumps. Or, as Vauban would have defined it technically, more circumspectly, a “composite fortress”; that is, an ancient site that has been patched up to meet the demands of modern warfare.

The old city walls had been supplemented with a few pentagonal bastions. There was no small number of them, and each had its own name, its own story; in themselves, they were real characters who were dear to the Barcelonans. But all those bastions had been built in different periods, with no overall plan and as though merely patched up. A few stretches of the wall were so long that the gunfire from one bastion could not serve as backup for the next, being too far apart. As for the dry moat that had to stretch around the outside of the fortifications, the less said about that, the better. It was so full of waste and debris, and so shallow, that you could see the ears of the pigs that grazed in it. A bankrupt government would find it hard to allow for whole squads of cleaners. The sieges at the end and beginning of the century had damned whole stretches of the perimeter. Amazing as it may sound, nobody had bothered to repair the holes. That is the position we found ourselves in. And now we had the barbarians ad portas . A devastating military machine, ignited by a hatred toward the “rebels” and trained through their experience in a long decade of campaigns. In under two weeks, they would be pitching camp outside Barcelona.

One might want to formulate this entirely legitimate question: If war came to the peninsula in 1705, and between that date and 1713 there were eight long years to fortify the city, how was it possible that the Catalans, who had their own government, never took care of the defenses of their city? This is one of my private torments, an argument that fills my nightmares and the distress of my wakeful hours. What could have happened? You should never have recourse to an “if. . ”; that “what if. .?” can kill. Because the answer, curiously, is neither political nor military. It doesn’t even have anything to do with matters of engineering.

Vauban was indeed the greatest military engineer of all time. But he was also French. In his study, using only ink and paper, he could create fascinating systems of defense, optimal and perfect, overwhelming in their geometric beauty. There was one problem with Vauban’s system of fortification and one only: It cost a lot of money.

Human imagination can develop at no cost, right up until the point at which it comes into contact with contractors. Tons of material, thousands of stonecutters, carpenters, and laborers, dozens of local specialists — or, more frequently, foreign ones, charging astronomical fees. Suppliers cheat, swindle, and defraud the government’s finances. The work drags on, the budget increases by a factor of three or four. And once the work has begun, how can it be suspended? A site that has been half-fortified is more useless than a half-built cathedral. You can praise God in a potato patch, but you cannot defend the city until the very last échauguette has been erected, humbly proud, on the point of the bastions. Even the most slow-witted of vegetable sellers understands that a wall needs to be closed up. Progress on a wall is in plain view of everybody, which puts considerable pressure on those in charge. They resign themselves to corruption. Opportunist agents in league with the technicians, the former supplying inadequate shipments and the latter signing for the receipt in exchange for an illegal “commission.” Money, always money. Themistocles was already saying as much: War is not a matter of weaponry but of money — whoever is the last person holding a coin. (All right, maybe it wasn’t Themistocles, it might have been Pericles, I don’t remember, but really, what difference does it make? Put any name you like to that quote. Anyone but Voltaire!)

Читать дальше