For what it is, or was, worth, the siege we were engaged in seemed an out-and-out disaster to me from day one. I am the first to recognize that war always has been, and will be, the art of negotiating shortages and imperfections. No campaign or siege has ever been conducted in optimum conditions. Quite the reverse: Something will always be missing. The man-at-arms, or the siege engineer, must have the gumption to improvise, to make the most of the situation (and trust that the enemy is on a level, or worse, footing). Vauban knew it, and that was why my technical instructions by the Ducroix brothers were always tempered by that one maxim: Débrouillez-vous! Deal with it!

Even allowing for the usual mishaps and limitations associated with war, Tortosa was a complete negation of all I’d learned at Bazoches. It had some value pedagogically: as an example to an engineer of what not to do. Ineptitude, in a siege situation, is paid for in blood.

An example. The first day, the very first day, of my studies in siege warfare, the Ducroix brothers etched in my memory the Thirty General Maxims of de Vauban, which pertained to any attack on a stronghold. Would you like to know what the very first one was? Well, then I’ll tell you.

Être toujours bien informé de la force des garnisons avant de déterminer les attaques : You must always be well informed as to the powers of the garrison before beginning your attack.

The calculations of Tortosa’s defenses proved useless: Orléans had found out that there were some fifteen hundred soldiers, among them English, Dutch, and Portuguese, set to stand against us on the ramparts. Among them, survivors from Allied troops at Almansa. But we noticed, once the attack had commenced, that their forces had multiplied: The civilians were lending enthusiastic support, so enthusiastic that the regular troops themselves were nonplussed. A further fifteen hundred men, the civilian militia, joined in, and everyone else was helping, too: women tending to wounds, children bringing pitchers of water to the bastions. I was dumbfounded. Why didn’t they hole up at home and wait for the storm to pass? Why would these simple peasants, to whom dynastic affairs were neither here nor there, risk taking part in a battle, as well as the reprisals in the case of defeat? Fool that I was, I was yet to realize that this was going to be the war at the end of the world — the end of the Catalan world, at least.

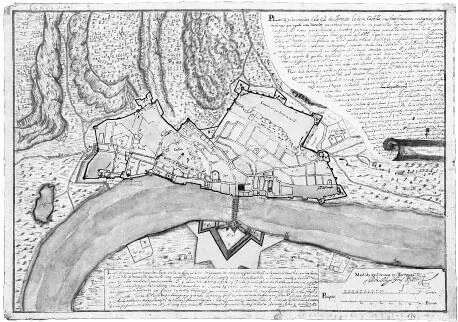

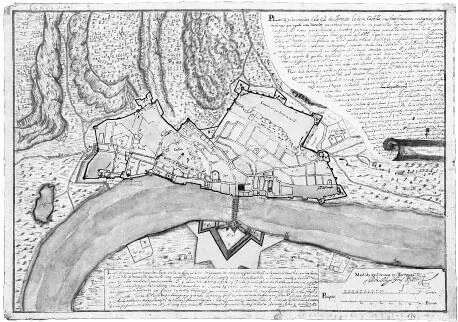

In the eyes of an engineer, Tortosa was an unusual city indeed. It had long been a strategically important spot, a military boundary, which meant there were a great many different fortification styles superimposed, from the Arabic rampart all the way to the very modern bastions. It sat on either side of the River Ebro, not far from where it met the sea — hence its strategic importance. In fact, the city was on the west bank, and a bastion stood protecting the east side. As a whole, it was thoroughly fortified. The Austrians had had their best engineers working on the defenses, preparing for a siege they rightly judged inevitable after Almansa. Most of the walls were modern, coming down at a sharp angle. Churches stood at the ends of certain parts of the cities, and then engineers had no qualms about turning these into makeshift bastions.

It made sense that Orléans would come up against such well-prepared defenses. Whoever controlled Tortosa would have the most important river route in Catalonia, and with it all routes south.

We struck the trench on July 20. As I explained in the opening chapters, “striking the trench” was the founding act for attacking any stronghold. Once your point of attack has been chosen, there’s no going back. Total defeat for the besieged, or disgrace for the attacking army.

I heard only on the nineteenth that the order had been given. “And the geological report?” I asked the Forgotten.

“Report? What report might that be, dear aide?”

Troops had been posted in the area where the trench was to begin, but no engineer had reconnoitered it. Really, the whole engineers’ brigade was full of dimwits, and most of them hardly knew what I meant. At first I thought they must be joking.

“We are going to strike the trench without doing a geological survey?” I asked.

“My, you’re meticulous!”

The grand event would happen, I was informed, the next day at eight in the evening. I put my hands to my head and straightaway went to entreat Monsieur Forgotten to hold off. “Sir, I have been told we are to strike the trench tomorrow.”

As ever, he was sitting in his tent, trying on a yellow wig in the mirror. He answered without looking at me. “Your information is correct. Which will give us the whole night ahead to dig under cover of darkness.”

“It’s not advisable, sir.”

“Oh?”

“It’s June, sir. It’s still light at eight in the evening.”

“You, sir, are a pessimist, not to mention a panicmonger.”

What Monsieur Forgotten did not mention was that he was oblivious, not to mention a wanton killer! I’ll explain why.

Striking a trench is always a highly delicate operation. Thousands of soldiers are gathered together, converted into peons, and made to line up at certain predetermined points under the cover of dark: rows of stakes joined together by a trail of lime on the ground. (I’ve participated in setting up the stakes at times, scrabbling along on your knees and in fear of your life.) The closer to the stronghold the trench can begin, the fewer days will be needed for digging. Counter to this, the closer to the ramparts it begins, the more likely it will be noticed. At this point the troops still cannot take refuge beneath ground — it was quite usual for the trench to begin within range of the defenders’ cannons — since the digging has only just begun.

Each of the men would have a pick or shovel, and thousands of the fajina wicker baskets would already have been lined up. The signal would be given and, as quietly as possible, digging begun all along the line. Each man would work behind the fajina , which the first shovelfuls would fill up, creating the first parapet in a matter of minutes, however precarious the situation.

Only a very disciplined troop, or one working at a very safe distance, would be able to move about undetected and at absolutely no risk. Predictably enough, the enemy sentries saw us, heard us, or, I’d say, possibly smelled us, given Monsieur Forgotten’s pungent patchouli. And what was bound to happen, happened.

Twilight in the west of Catalonia has an intensity and forcefulness all its own; the throes of the day come erupting into the sky in oceanic blues and reddish ambers. As cannon fire commenced, a strip of maroon lit up the horizon.

There were fifty or so Allied cannons at Tortosa, of all calibers, and they began to pound our positions immediately: 2,200 excavators turned to 2,100, and in no time at all, 2,000. A chronicle I read subsequently referred to that night of horrors with the following lovely phrase: “The cannonade that night was a delight to hear.” Those historians might save “delight” for describing royal weddings, I say!

It couldn’t have gone any worse. Everything that Vauban foretold, all the possible things that can go wrong in a siege, came about. Another example: As a rule, commanders in the artillery tend to love blowing things up. At the first chance, with a childlike joy, they will commence firing. As happened in Tortosa. The first parallel had not even been dug, and our chief of artillery was already there, ordering fifteen cannons and six mortars be installed — at positions we had not even touched with pick or shovel. The problem being that the first parallel is at such a distance, nearly a mile from the ramparts, that cannonfire won’t land anywhere near. If the guns are accurate enough to land any shots on a rampart or bastion, that is. A great many hundredweights of gunpowder and ammunition for nothing. I objected; Monsieur Forgotten didn’t even hear. What did it matter to him? The artillery chief was one of his revelers par excellence, and in any case, neither of them would have to cough up for the powder.

Читать дальше