I was so dazed that I felt like I was seeing with my ears and hearing through my eyes. There were shreds of meat everywhere, remains similar to the formless gobbets you tend to see on the floor of an abattoir. I lifted my gaze. From the top of the bastions, the burning, howling bodies of Coronela men were falling after they leaped off the edge, as if the bastion were a burning ship. I saw all these things and then said to myself: “Ladies and gentlemen, enough. This is more than good old Zuvi can bear. To the hell with the city, the home country, and the constitution.” I turned on my heel and ran like a rabbit.

“Fear will rise up into your eyes,” I was told in Bazoches, “and do the looking on your behalf. Don’t let it.” Not bad in the context of a classroom. But when a power comes to bear that can make a bastion lurch and teeter like a paper boat, not even the memory of Bazoches could quash an individual’s self-preserving instinct. I wasn’t the only one who ran. Dozens of men had been pushed beyond their limits and were fleeing in all directions. I crossed the cutting and entered the city streets before being confronted by a huge crowd.

Women, in droves. They were holding their skirts clear as they ran — but in the opposite direction: toward the walls. Amelis was among them. “What’s happening, Martí, what’s happening?” she asked, but didn’t stop. They’d been drawn by the explosion, and the prevailing chaos had meant there was no one to stop them from reaching the front line. Those of us who had succumbed to panic and fled, now hesitated.

In my view, Barcelona’s rescue that night owed more to its women than Timor’s saber. We fugitives were deemed cowards, picaroons, eunuchs. Amelis halted and called back at me: “You mean you’re going to let the enemy enter?”

Allow me a moment’s reflection in place of memories: What ideal was it that motivated the people of Barcelona to keep on going throughout a yearlong siege? Their liberties and constitutions? No, what kept them there was that bond — heavenly or demonic, it matters not — that prevents a man from abandoning the spot he’s fighting on. Raw civilians, fourteen-year-old boys, sixty-year-old grandfathers, clung like limpets to the bastions. And why? I’ll suggest an answer: because of the overwhelming, unshakable force of the question: “What will people think?” When your whole city’s watching, it takes a lot of courage to be a coward.

Thus, even a prissy rat like Longlegs Zuvi went back to his post. And that whole night we resisted an irresistible force, and through the next morning, and come midday next, good old Zuvi’s nerves were utterly shredded, as was the case with the rest of the Coronela.

The center of Saint Clara was now a crater, a solemn gap clung to by what was left of the bastion’s five walls. The unutterably mad struggle was for possession of this gap. The hail of rifle volleys was unceasing. And still no offensive from Don Antonio. Throughout this period, Jimmy continued to smugly accumulate men on the first barricade. Time was on his side. He thought (as I did at the time) that Don Antonio had taken leave of his senses — or even his valor — and was relinquishing the defensive positions. Once enough Bourbon battalions had gathered behind the first barricade, there would be no way of stopping an onslaught from them. And there we were, doing nothing but holding the second barricade and firing from Portal Nou and the adjacent sections of the ramparts. A lot of noise but little else came of it: rounds upon rounds of bullets spent while the Bourbons kept their heads down behind the first barricade and in the trench, or came along the cut, digging in deeper and building their parapets higher with every hour that passed.

It had been hell maneuvering the three cannons up to the bastion. And rather than firing those cannons, the Mallorcans wouldn’t so much as peek out of the embrasures. As ever, it was as though they were fighting a separate battle from everyone else. They sat around on the bases of the cannons, drinking an abominable liquor from the Balearics — sharing it with none but themselves — and seeming removed from the bedlam surrounding them.

“For the love of God,” I said, “fire these cannons, blow up the barricade they’re holding! What are you waiting for?”

Their captain shook his head, his only concession being to mutter at me in his islander accent: “ Ses ordres .” Orders.

There was a considerable stretch of ground between the end of their trench and the bastion because, as per good old Zuvi’s modifications to Verboom’s plan, the third parallel had been dug as far from the ramparts as possible.

I later learned that it had never been Don Antonio’s plan to take back the first barricade. Jimmy was too strong there, it would only have been a bloodbath, so Don Antonio was content to delay them. He waited until the last possible moment before launching his counterattack, anticipating some pause in the assault. Then and only then did he give an order, one that just three officers had been let in on.

Lowering the telescope, he called out in that booming Castilian voice of his: “Do it!”

A flare went up, turning red the thick smoke on and around the bastion and ramparts. The moment he saw this, Costa gave his signal, lowering an arm. I wasn’t nearby, but I believe I heard him shout something as well, and within an instant, each and every cannon and mortar began pounding the trenches, creating a barrier of flames.

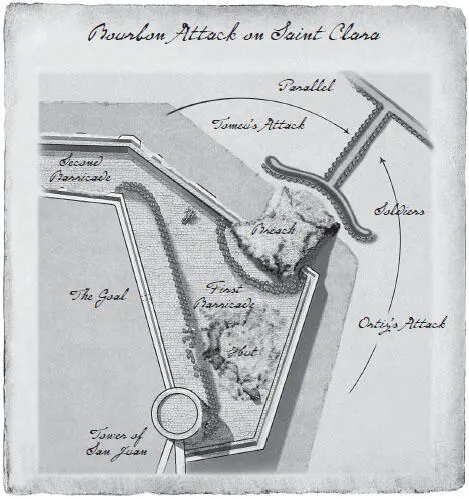

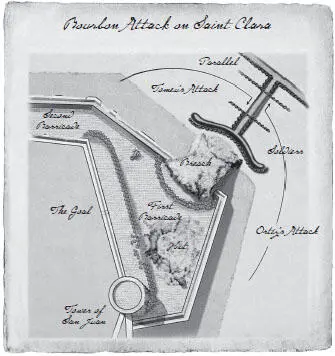

We saw the explosions hitting the Bourbon lines, and the next two troops charging out from the garrison, one from the left and one from the right. (The arrows on the plate below indicate their trajectories.)

Two hundred previously selected men, under Lieutenant Colonel Tomeu and Colonel Ortiz, attacked each flank. And my God, what a mad dash that was.

They hurtled out alongside the third parallel, exposing themselves to fire from the trenches. Those four hundred had to be very fast to make the most of Costa’s barrage. They converged on the cut, some jumping down inside and others tipping the fajina parapets onto the heads of the enemy. Like this:

Ortiz was in charge of blocking off the cut on the side of the Bourbon encampment with the fajinas , and Tomeu’s men did the same on the city side, trapping the enemy in between.

This was one of the swiftest and most exact maneuvers I’ve ever seen carried out from a besieged position. If Costa hadn’t been a superior artilleryman, his cannons and mortars would have been the death of that four hundred. We watched as, having reached the cut, they shot their rifles down into it, annihilating the surprised Bourbons. I still have trouble banishing the memory of that underground wailing.

By the time Jimmy found out, it was too late. With Ortiz blocking the cut, there was no longer any use sending reinforcements.

As for the Bourbons already on Saint Clara, they saw what a sticky position they were in, with Tomeu behind them. And that was when the three cannons manned by the Mallorcans came into play: A large section of the first barricade sank, the brickwork beneath it pummeled so hard that it buckled inward and down.

With cannonballs coming from one side and rifle bullets riddling them from the other, the Bourbons scattered, leaping down into the moat below and sprinting past Tomeu’s position, trying to reach the trench. It goes without saying that Ortiz’s and Tomeu’s men mercilessly gunned them down at close range. The volleys from the rifles up on the Saint Joan tower also intensified, prompted by the sight of the stampede. And then the order came for those of us on the second barricade to charge the first and, finally, unopposed, retake it.

Читать дальше