Midway through the afternoon, four Spanish soldiers came in, sent by a captain. They made me go with them in spite of my protests. Their bearing didn’t seem particularly soldierly, which is to say they seemed very slovenly, and everything they did seemed strained, as happens with men unwillingly obeying orders. As they dragged me through camp, they kept glancing from side to side, as though afraid someone else would step in and stop them.

The unfortunate houses on the site of the Bourbon camp had been turned into stores or residences for the high command. They took me into one of the latter. We climbed some steps up to the first floor, and I was locked in a room containing an old table and two shabby-looking chairs. A fine layer of dust covered the floor and furniture. The panes in the single window were smashed. The Bourbon camp was the sack, and this tiny room a sack within the sack. Jonah in the belly of the whale? He had nothing on me then!

“Our man”—in the words of the innocent Dupuy — appeared half an hour later. I saw what had happened. Dupuy, just arrived at the Bourbon encampment, was met by a Points Bearer who showed himself to be compliant and polite. In the belief that the sacred fidelities of Bazoches were still in effect in the world, Dupuy had placed full confidence in the man.

“Our man” came in and immediately reprimanded the soldiers he had with him. Why hadn’t his guest, the honorable enemy, been given drink and plenty of food? But with his hands, in our sign language, he said to me: “I’ve got you, you swine.”

“Our man” was none other than Joris Prosperus van Verboom, the Antwerp butcher.

When everything was over, after Barcelona had fallen and the war was drawing to its close, Verboom was given some very cushy sinecures indeed by Philip V. He stayed on in Catalonia. Barcelona — defeated, flattened, bloodied — remained a source of unease to the Bourbons. There is a form of submission more absolute than death: endless slavery. Little Philip gave the task to Verboom.

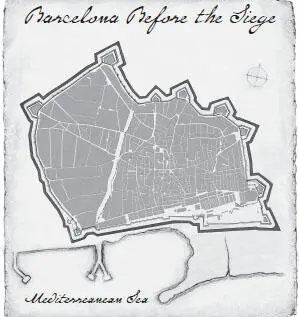

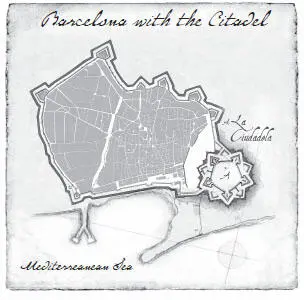

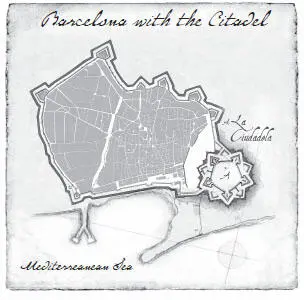

I’m going to include two very rough sketches of the city — if my hairy hippopotamus manages not to lose them, that is. The first one you’ve already seen; it’s of old Barcelona as it was immediately before the siege.

And in this next one, you can see what Verboom did to it.

The star that’s been added on, the Citadel, was the work of Verboom. Yes, the Citadel. He leveled a fifth of the city for building materials. A perfect bastioned enclosure, there not for the people’s protection but from which to control, subdue, and, if necessary, fire cannons on them. An urban tumor that converted Barcelonans into prisoners in their own city.

But what am I doing talking about what happened after the siege? Held captive behind enemy lines, in the hands of my enemy, I had quite enough on my plate.

My usual quick thinking had deserted me. My only way out was to get in touch with Dupuy. Impossible: Verboom stood in my way; a man capable of plotting my kidnap must have been sufficiently foresighted to hide that fact. Most likely, he was going to kill me there and then. And later, he’d allege that I’d tried to get away, and say to Dupuy that some imbecile soldier had shot me by mistake — anything. Shit.

Verboom had arrived in the night, like a sea mist, or like deathly fevers. I’d managed to make myself a weapon, a knife fashioned out of some wood I’d pulled off the window frame and, for the blade, a shard of glass thrust into it. If worse came to worst, before they tried to kill me, I’d try to take his eye out.

However, I quickly saw that the situation was not as I had imagined. The Antwerp butcher brought one servant soldier with him, and his only weapons were a tray, a bottle, and two glasses. The servant put these down on the table and went out. When Verboom and I were alone, I erupted in indignation. “How dare you lock me up! I defect, I offer my services to King Philip, and this is my reward. You can’t imagine what I’ve been through, coerced by those rebels to take part in their deluded attempts to defend their city!”

Verboom’s only response to my theatrics was to take a seat, pour wine into the two glasses, and say: “Drink.”

I refused. He could have been planning to poison me, to save himself from having to do something violent and then for Dupuy to find out.

“Come now, don’t be ridiculous,” he said, grimacing. “Think I’d go so low? This is good port — using it as rat poison would be a waste.”

He took my glass and drained it in one go. But it would take more than that to win my trust. The silence was eventually broken by the rumbling of cannons starting up outside. The walls shook, and chalk dust fell across the table. Intuitively, Verboom put a hand over his glass, glancing up, which actually convinced me: No one tries to preserve a drink with poison in it. I poured myself some more port and felt it strip my throat. What was Verboom up to? He wasn’t exactly getting to the point.

Jimmy was going to arrive within a matter of days. The person whose Attack Trench design ended up being used to take Barcelona would gain a large share of the praise. When he was released in 1712, Verboom made a plan for a future siege of the city. But Jimmy had sent Dupuy ahead to design another trench. Dupuy was a Seven Points. Jimmy was very likely, in any case, to use the trench of a Vauban family member, which would make all the butcher’s efforts for naught. Goodbye, glory, goodbye, rewards!

In a nutshell: Verboom was hoping I’d correct, refine, and improve the trench he’d been planning. I was a Five Points — well, sort of — and had the advantage over Dupuy of having been inside the city and therefore knowing what state the defenses were in.

In spite of my situation, I burst out laughing. Did he really think I was going to help him?

“You’re the reason I spent two years locked up,” he said. “Two long years.”

At this point, his hate for me became more than palpable. Everything about Verboom was large: his body, his head, his teeth, like those of a hippo. I gulped, suddenly very afraid. He paused, letting me savor his intimidating force. I was under lock and key, and I was alone; he could do with me as he pleased. And we are all what we are; Saint Jordi killed the dragon as easily as crushing a cockroach, Roger de Llúria brushed aside a hundred thousand Turks over the course of three breakfasts, and King Jaume took Mallorca and Valencia just because he felt bored with his palaces in Barcelona. But as it turned out, Longlegs Zuvi wasn’t Saint Jordi, or Roger de Llúria, or King Jaume. I was simply very, very afraid.

“I did nothing to you. Nothing!” he bellowed. “One day I was at Bazoches castle, courting a lady, and a muddy gardener crossed my path. What have I got against gardeners? Nothing. But that day in 1706, I was slandered — vile slander — and four years later, in 1710, I was captured — again, vilely — and now, another four years on, here’s this vile gardener again. Except this time, there’s nothing to stop me ridding myself of you. Nothing!” He wagged a finger at me. “And yet there is a small possibility I might let you off. If you do as I tell you, I’ll merely exile you to the island of Cabrera or some such godforsaken spot.”

He left me alone to think about it. He left the drawings for the trench he’d designed, along with some scraps containing the technical details. I didn’t bother looking at them. A prisoner has obligations, and he has rights, which add together to form the only thing he must do: escape.

Читать дальше