Consider another more condensed example of Leduc’s attentiveness to the multivariable experience of sexuality. La Bâtarde recounts several outings taken by the young Leduc and her mother to see different shows while they were living under the same roof in Paris. (They once went, for instance, to see the cross-dressing aerialist, Barbette.) As they set out on one such outing, Violette takes her mother’s arm:

“Don’t put your arm through mine. You’re such a farm boy [ paysan ]!” she said.

Farm boy. The use of the masculine really got to me. (2003, 127)

In one very compact utterance, Leduc’s mother registers her impression of her daughter’s sexuality, subtly linking together gender, object choice, and that odd mixture of regional identity, class, and race that is contained in the French concept of peasant, paysan . Leduc’s representations of her mother’s reactions to the sexually dissident forms of behavior she exhibits while growing up provide interesting evidence of a point of view (her mother’s) that is neither exactly approving nor exactly disapproving, but is certainly matter of fact about such expressions of dissidence. When Leduc is expelled from her girls school because of her sexual relations with one of the teaching staff, she is sent by train to Paris, where her mother is now living. Her mother meets her at the station:

I saw my mother in the first row: a brush stroke of elegance. A young girl and a young woman. Her grace, our pact, my pardon. I kissed her and she replied: ‘Do you like my dress?’ We talked about her clothes in the taxi. My mother’s metamorphosis into a Parisienne eclipsed the headmistress and sent the school spinning into limbo. Not the slightest innuendo. Giving me Paris, she gave me her tact. (111)

There is a complicity between mother and daughter, a shared choice not to take up the subject of Leduc’s behavior or its consequences. We might see behind this complicity a shared set of reference points regarding sexual culture. The sexual culture of the countryside, villages, and towns they came from was, while not the same as what they see around them in Paris, already a rich, diverse, and conflicted one, which means that they were both in full possession of a practical understanding of sexual diversity and dissidence that allowed them to communicate with and understand each other on all sorts of implicit levels.

This practical understanding of sexual diversity that Leduc shares with her mother is, of course, present in her letter to de Beauvoir as well. Her practical understanding tells her that her love for de Beauvoir, the relationship between the two women she encounters that summer, and the sexuality of Parisian lesbians are all related and yet different. We could say, borrowing the term mobilized so influentially by Kimberlé Crenshaw, that Leduc and her mother have a practical understanding of sexuality that is fundamentally intersectional. José Esteban Muñoz glossed Crenshaw’s term in the following way: “Intersectionality insists on critical hermeneutics that register the copresence of sexuality, race, class, gender, and other identity differentials as particular components that exist simultaneously with one another” (Muñoz 1999, 99). We might well imagine that Leduc’s experience of her own sexual idiosyncrasy, and her practical ways of understanding distinctions between different sexualities she perceives around her somehow involve an experience of intersectionality, and that among the identity differentials that count for her are differentials between country life, small town life, and city life, and also, the topic to which I now turn, differentials between people involved in literary or intellectual pursuits (herself, de Beauvoir) and those who are not.

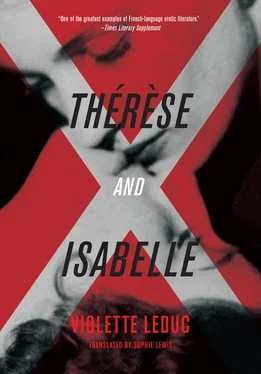

However seriously Leduc may be taken by writers like Sartre, Jouhandeau, Cocteau, Genet, and de Beauvoir, something about her being a woman means that both the social world and the gatekeepers of the literary field treat her differently than they treat, say, Genet. Leduc registers this aspect of her situation in many ways, including the portrayal, in La Chasse à l’amour, of the mental and physical distress she experiences following Gallimard’s refusal in 1954 to publish those sections of her novel Ravages having to do with the sexual relations of Thérèse and Isabelle at boarding school (the text reprinted in this volume), the representation of an abortion and its aftermath, and several other passages. If these passages were so important to her, it is because she understood them to be a key part of her attempt to break new ground in literature, just as Genet was doing. One can also trace in her correspondence with de Beauvoir from a few years before this episode, her sense that de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex had a similar kind of importance for the evolution of culture. She expresses her support for de Beauvoir as she confronted the violently misogynist reactions to her book, and she told her of her pride at being cited by de Beauvoir in the volume. “I thank you with all my heart for citing me on several occasions,” she writes in 1949. “What touched me was the actual moment during which you were writing my name in a serious book” (Leduc 2007, 130).

Leduc’s sense that she, Genet, de Beauvoir, and Sartre were breaking important new ground in the ways they struggled to represent sexualities that previously had no place in serious writing finds further expression in a letter from the following year. Early in 1950, Leduc makes a comparison between the audacity of Genet in his novels and the audacity of de Beauvoir in The Second Sex: “Genet’s authority appears as strong as ever when you reread him. How salubrious are all the sexual audacities to be found in contemporary literature! I could feel the world-wide barrier of resistances begin to give way as I read volume 2 of The Second Sex, as I reread Genet” (Leduc 2007, 142). Clearly she meant for her own writing in these years to contribute to this same project. This helps explain why the frustrations of seeing her work censored, along with the frustration of the poor sales of her books, was almost too much for her to bear.

A scene in the recent French biopic devoted to Leduc develops this commonality, by showing de Beauvoir defending Leduc against her censors at Gallimard, accusing them of being unable to bear the idea of a woman speaking openly about sex between women, and insisting on the urgency for abortions — at the time illegal in France — to be a topic that could be written about in both literary and philosophical contexts ( Violette 2014).

For Leduc, being involved with literature was part of her experience of sexuality. Early in La Bâtarde, she describes for her readers how, around the age of sixteen, she related to a provincial bookstore:

I also walked in the Place d’Armes on Saturday nights. The lighted storefronts crackled before my eyes. I was attracted, intrigued, spellbound by the yellow covers of the books published by the Mercure de France, by the white covers of the Gallimard books. I selected a title, but I didn’t really believe I was intelligent enough to go into the largest bookstore in town. I had some pocket money with me (money that my mother slipped me without my stepfather’s knowing), I went in. There were teachers, priests, and older students glancing through the uncut volumes. I had so often watched the old lady who served in the shop as she packed up pious objects, as she reached into the window for the things that people pointed out to her. . She took out Jules Romains’ Mort de quelqu’un and looked at me askance. I was too young to be reading modern literature. I read Mort de quelqu’un and smoked a cigarette as I did so in order to savor my complicity with a modern author all the more. . The Saturday after that I stole a book which I didn’t read; but I paid cash for André Gide’s Les Nourritures terrestres ( The Fruits of the Earth ) and a sculpture of a dead bird. Later, under my bedclothes, when I went back to boarding school, I returned to the barns, to the fruits of André Gide by the glow of a flashlight. As I held my shoe in the shoe shop and spread polish on it, I muttered: “Shoe, I will teach you to feel fervor.” There was no other confidant worthy of my long book-filled nights, my literary ecstasies. (2003, 51–52)

Читать дальше