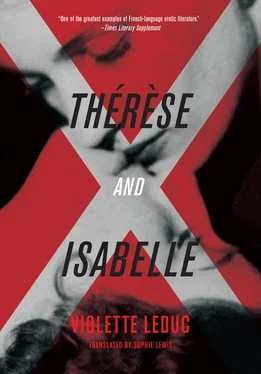

Violette Leduc

Thérèse and Isabelle

We began the week every Sunday evening in the shoe room. We polished our shoes, which had been brushed at home that morning in our kitchens or gardens. We came in from the town; we were not hungry. Keeping away from the refectory until Monday morning, we would make a few rounds of the schoolyard, then go two by two into the shoe room accompanied by our bored supervisor. The shoe room at our school was nothing like those street stands where all the nailing, the shaping, the hammering send your feet hurrying back to the pavement outside. We polished in a poorly lit, windowless chapel of monotony; we daydreamed with our shoes on our knees, those evenings that we came back to school. The virtuous scent of polish that revives us in pharmacies here made us melancholy. We were languishing over our cloths, we were awkward, our grace had abandoned us. The new monitor sat with us on the bench, reading aloud and lost in her tale, gazing far beyond the town, beyond the school, while we carried on stroking leather with wool in the half-light. That evening we were ten pallid returnees in the waiting-room gloom, ten returnees who said not a word to each other, ten sullen girls all alike and avoiding each other.

My future will be nothing like theirs. I have no future at the school. My mother said so. If I miss you too much I’ll take you home again. School is not a boat for the other boarders. She might take me back home at any moment. I am only temporarily on board. She could take me out of school on a first day of term, she could take me back this evening. Thirty days. Thirty days I’ve been a passenger at the school. I want to live here, I want to polish my shoes in the shoe room. Marthe will not be called back home. . Julienne will not be called home. . Isabelle will not be called home. . They are certain of their futures, although I’m willing to bet that Isabelle spits on the school each time she spits on her shoe. My polish would be softer if I spat as she does. I could spread it further. She is lucky. Her parents are teachers. Who is going to snatch her away from school? She spits. Perhaps she is angry, the school’s best student. . I am spitting like her, I moisten my polish but where will I be a month from now? I am the bad student, the worst student in the big dormitory. I don’t care in the least. I detest the headmistress, spit my girl, spit on your polish, I hate sewing, gymnastics, chemistry, I hate everything and I avoid my companions. It’s sad but I don’t want to leave this place. My mother has married someone, my mother has betrayed me.

The brush has fallen from my knees, Isabelle has kicked my polish brush away while I was thinking.

“My brush, my brush!”

Isabelle lowers her head, she spits harder on the box calf. The brush rolls up to the monitor’s foot. You’ll pay for that kick of yours. I collect the object, I wrench Isabelle’s face around, I dig my fingers in, I stuff the rag blotched with wax, dust, and red polish into her eyes, into her mouth; I look at her milky skin inside the collar of her uniform, I lift my hand from her face, I return to my place. Silent and furious, Isabelle cleans her eyes and lips, she spits a sixth time on the shoe, she hunches her shoulders, the monitor closes her book, claps her hands, the light flickers. Isabelle goes back to shining her shoe.

We were waiting for her. She had her legs crossed, rubbing hard. “You must come now,” said the new monitor timidly. We had come into the shoe room with clattering heels but we left muted by our black slippers like phoney orphans. Close cousins to the espadrille, our slippers, our Silent Sisters, stifle wherever they step: stone; wood; earth. Angels would lend us their heels as we left the shoe room with cozy melancholy flowing from our souls down into our slippers. Every Sunday we went up to the dormitory with the monitor; all the way there we would breathe in the rose-scented disinfectant. Isabelle had caught up with us on the stairs. I hate her, I want to hate her. I would feel better if I hated her more. Tomorrow I’ll have her at my table in the refectory again. She’s in charge of it. She’s in charge of the table I eat at in the refectory. I cannot change my table. Her sidelong little smile when I sit down late. I’ve put that sly little smile straight. That natural insouciance. . I’ll straighten out that natural insouciance of hers too. I’ll go to the headmistress if necessary but I shall change my table in the refectory.

We entered a dormitory in which the dim sheen of the linoleum foretold the solitude of walking there at midnight. We drew aside our percale curtains and found ourselves in our unlockable, wall-less bedrooms. Isabelle’s curtain rings shunted along their rail just after the others’. The night monitor paced along the passage. We opened our cases, took out our underwear, folded it away on the shelves in our wardrobes, keeping out the sheets for our narrow beds, we threw the key into the case which we now closed for the week, we put that away in the wardrobe too, and made our beds. Under the institutional lighting our things were no longer ours. We stepped out of our uniforms, hung them up ready for Thursday’s walk, folded our underpants, laid them on the chair, and took out our nightgowns.

Isabelle left the dormitory with her pitcher.

I listen to the tassel of her gown rustling over the linoleum. I hear her fingers’ drumming on the enamel. Her box opposite mine. That’s what I have in front of me. Her coming and going. I watch for them, her comings and goings. Were you tight? Got good and tight? This is what she says when I come in late to the refectory. I’ll flatten that sarcastic smile of hers. I didn’t get tight. I was practicing diminished minor arpeggios. She is scornful because I hide away in the music room. She says that I make a din, that she can hear me from the prep room. It is true: I do practice but all I make is noise. Her again, always her, again her on the stairs. I run into her. I would have undressed slowly if I had known she was at the tap fetching water. Shall I run away? Come back later when she is gone? I won’t go. I am not afraid of her: I hate her. She has her back to me. What nonchalance. . She knows there is someone right behind her but she will not hurry. I would say she was provoking me if she knew that it was I but she doesn’t know. She is not curious enough even to check who is behind her. I would not have come if I’d known she would be dawdling here. I thought she was far away — she is right here. Soon her pitcher will be full. At last. I know that long, loose hair of hers, there’s nothing new about her hair for she walks about like that in the passage. Excuse me. She said excuse me. She brushed my face with her hair while I was thinking about it. It is beyond belief. She has tossed her hair back so as to send it into my face. Her mass of hair was on my lips. She didn’t know I was behind her and she flicked her hair in my face! She didn’t know I was behind her and she has said excuse me. It is unbelievable. She would not say I’m keeping you, I’m being slow, the tap isn’t working. She tosses her hair at you while asking you to excuse her. The water flows more slowly. She has touched the tap. I will not speak to her, the water has almost stopped, you will not prize a word out of me. You ignore me, I shall ignore you. Why did you want me to wait? Is that what you wanted? I shall not speak to you. If you have time to spare, I have time too.

The monitor has called us from out in the passage, as if we were in league together. Isabelle went out to her.

I heard her lying, explaining to the new monitor that the tap had gone dry.

The monitor is talking to her through the percale curtain: are you eighteen? We are almost the same age, says the monitor. Their conversation is cut short by the whistle of a train escaping from the station that we left at seven. Isabelle soaps her skin. Tight. . Did you get good and tight? Who can say what she is thinking? This is a girl with something on her mind. She’s dreaming or else she spits; she dreams and works harder than the rest.

Читать дальше