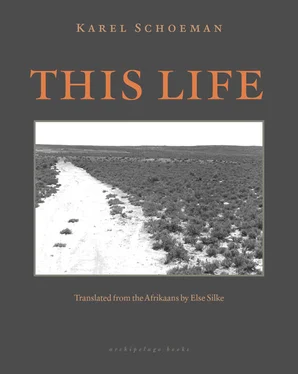

Karel Schoeman - This Life

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Karel Schoeman - This Life» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, ISBN: 2015, Издательство: Archipelago, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:This Life

- Автор:

- Издательство:Archipelago

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:978-0-914671-16-9

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

This Life: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «This Life»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

considers both the past and future of the Afrikaner people through four generations of one family. In an elegiac narrator's tone, there is also a sense of compulsion in the narrator's attempts to understand the past and achieve reconciliation in the present. This Life is a powerful story partly of suffering and partly of reflection.

This Life — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «This Life», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Of the books Sofie and I read together like that, I understood very little at first, but Pieter borrowed them from her, and it was a secret between the three of us that had to be kept from Mother. She never caught him reading, for she would have taken the book from him and she might even have given him a thrashing, grown-up as he was, but she did know about it, just as she knew about everything else. “He’s lying about somewhere outside again, reading,” she exploded towards Father when some or other chore had been neglected or overlooked, and the words were also a reproach aimed at Sofie whom she never accused directly. “You must speak, husband, you must speak!” she cried out with her usual vehemence, but Father just smiled and stroked his beard defensively as was his habit. When the two boys got into an argument, Jakob sneered at Pieter’s book-learning and his preference for the women’s company, but Pieter only retreated into an unwonted silence and made no reply.

Sofie and Pieter and I at the voorhuis table, Pieter’s blonde head bent over the quill pen he was carving for her; Pieter handing it across the table, and Sofie reaching out her hand to take it from him, while I glanced up from my seat beside her and noticed it: a gesture like so many others among people who live in the same house and share the same life, passing the knife, the bowl, the leather thong, the candle, and accepting it without a further thought. Why then do I remember the passing of the pen rather than that of knife or bowl, candlestick or thong? Outside the dams were blinding in the sun, for the fountains were running strongly after the winter’s snowfall and the pools were full; among the bulrushes and the reeds the water caught the light and the hollows were sodden. Sometimes Sofie and Jacomyn would disappear together and leave me alone inside the house with Mother and her silent but unmistakable disapproval, and only at dusk would they return. Or was there only that one occasion, that evening when they arrived home agitated and afraid after the candle had already been lit in the voorhuis? They had gone for a walk to pick flowers and some children had thrown stones at them — was that the way it happened? I must have been half-asleep by that time and I only remember the agitated voices; they must have stumbled on the shelter of one of our herdsman families in some remote part, and the children they came upon were unused to strangers, or took fright at the white woman, and threw stones at them. I remember how angry and upset Mother was and how furious Jakob became, while Father tried to soothe and appease. Were they raging at the children, or was it Sofie who had infuriated them with her irresponsible behaviour? I still remember Jakob’s dark face and how he struck the table with his fist and threatened to chase the people at Bastersfontein away once and for all so that they would never return; but is that really the way it happened, was it Bastersfontein he mentioned that evening in the candlelight, or are there other memories that have become entwined with what I recall of that evening? Was that the evening when the chair fell over and the door was slammed shut? Out of cobwebs and shadows my imagination weaves illusions in an attempt to find something I can understand. Dimly, dimly, across the years, through the dreams, through the drowsiness of the child who once heard it all through a haze of sleep I remember the clamour of the angry voices by candlelight, the chair, the door; I remember the thatched roof collapsed over the walls of the house and the dried-up fountain where no mud retained a print any more.

How rich the Roggeveld always was for a few weeks after the end of winter, when the wild flowers appeared in the bright light and cold wind of the tentative spring, the only wealth that meagre land ever knew. I remember the spekbos radiant-white like a snowfall along the rocky ridges, large patches of yellow katstert, blazing like candles, and the fields of kraaitulpe like fire, the gous-blomme and botterblomme and perdeuintjies, and when the scattered clouds swept past the sun, the entire bright veld creased and furrowed like water, and the people moving across it were like swimmers on the surface of a dam, rolling on the waves of shadow and light. As the women approached, laughing, their hands filled with flowers, their feet were tangled in the shadows; Pieter stumbles as he runs towards us and for a moment he is carried forward by the surge, his golden hair gleaming in the sun. How did Pieter manage to extricate himself from his work and slip away to come with us? Laughing, he reaches out with his hands to break his fall, laughing, he struggles against the swell and for a moment remains afloat on the heaving surface where he is caught by the sunlight, and then the dark water washes over him and obscures him from my view. The women’s voices waft away on the wind so that I can no longer hear Sofie and Jacomyn calling my name; I start, and see Sofie standing before me, her dress flapping in the wind, and the flowers she has picked fall from the careless posy she holds out to me and are blown away by the wind. Impatiently she presses the flowers into my hand and turns around, turns away from me, and disappears into the tide of sliding, shifting shadows and light; laughing, she runs after Pieter, while Jacomyn remains standing beside me, following them with her eyes.

It was during the spring after Sofie’s arrival, that spring and summer, I presume, because I am bewildered by the succession of bright days and I can no longer distinguish one from another; but that summer she was already pregnant with Maans and everything was different, not only because the birth of the child would determine the date of our usual departure for the Karoo or because Sofie was more often indisposed as her pregnancy progressed, but because of the high expectations the birth of Jakob’s son raised in Mother, so that Sofie was treated with a newfound attentiveness and consideration, and the pregnancy and approaching confinement were increasingly allowed to influence even the most important arrangements and routines of our daily lives. This was the child of the eldest son, the first grandchild and the future heir, and from the way Mother was preparing for his birth, I must conclude as I look back now that she had begun to amass his inheritance much earlier, even though the process was evident only occasionally, as with Bastersfontein and Kliprug.

That summer Sofie was pregnant, and when I think of that summer my first memory is of Jakob and Pieter and Gert harvesting corn in our field, and of Pieter’s pale body as he stood on the wagon, laughing in the sunshine. By this time Sofie was walking with difficulty and had to lean on me over the uneven surface of the track; yes, now I remember how it was, and it becomes clear again how those memories fit together. Gert had come back home to fetch the wagon, and Sofie came running to where I was busy in the voorhuis. “Come, Sussie, let’s go along to the corn-field!” she whispered as if it were a secret that no one else should know, and we slipped out through the kitchen and disappeared around the corner of the outside room quickly before anyone could see us from the house. We followed behind the wagon, trying to catch up with it, Sofie’s hand on my shoulder as she leaned on me heavily over the uneven rocky track across the veld; but though she moved with difficulty and was soon out of breath, she was laughing like a child, driven by an excitement which swept me along though I did not understand. Laughing and out of breath, we caught up with the wagon and climbed aboard, and so we reached the cornfield where Jakob and Pieter were harvesting together. To me it was just an adventure and it was only when we arrived there that I realised from Jakob’s outburst how much I did not understand yet. What was the reason for his anger? Sixty years later I still cannot understand it. Jakob had never shown any consideration, neither had he ever been particularly attentive to Sofie as far as I can remember; could it have been Mother’s disapproval and reprimand he feared, or did he in some way not quite clear even to himself sense that his authority as Sofie’s husband was at risk, did he already begin to sense he was losing her and she was slipping away from him in the golden haze of candle-light and dust, into the dark depths of the shadowy water? Jakob had always been a strange man with his silences and his outbursts, and who could say what was hidden behind them? To this day I struggle to find an explanation or an answer, so what can one expect from the child in the cornfield sixty years ago? Mystified, I knelt on the ground and watched them as they stood there, Jakob and Sofie and Pieter, in the summer sun in the field where the sheaves were stacked, and I realised they were grown-ups whose lives I did not understand: I remember the heat and the silence and Jakob’s fury, and how the tap of the water barrel beside me was dripping and had formed a moist, dark patch in the soil. I poured a little water into a bowl to drink and to splash on my burning face, and then Sofie sat down beside me on the ground and I poured her some water too, while the men began to stack the sheaves on the wagon, Jakob and Gert handing them to Pieter, who stood on the wagon, so that the load was stacked higher and higher until they had to throw the sheaves up to him with pitchforks.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «This Life»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «This Life» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «This Life» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.