Apart from these and the above-related facts, the character of Alistair in the novel has little in common with my grandfather, and certainly the book’s plot is an invention. The novel is inspired by my grandfather and it would not exist without him, but it is not at all based on his true story.

The story begins in London, of course. Mary North became its central character for the same reason Randolph Churchill did not: that bravery is more subtle when one has a great deal to live for. Also, I had learned by now that I should draw on my family’s history rather than presume to know the world’s. If I could dig only a small hole, then it might at least have careful edges. The character of Mary is inspired by my paternal grandmother, Margaret Slater, who drove ambulances in Birmingham during the Blitz, and by my maternal grandmother, Mary West, a teacher who ran her own school and kindergarten.

Neither of my grandmothers could ever be persuaded to talk about the war, or if they did then it was simply to fend off our questions with a smile and a wave of the hand. Talking with them as children we got the impression that the war had been brief, uncomfortable and not worth wasting breath on — like a camping holiday that had been marred by rain. One would not guess that Margaret, an artist, had driven an ambulance through bombs. One would never suspect that Mary’s first fiancé had been killed at her side in a cinema in an air raid on East London, which nearly killed her too and of which she always bore the scars.

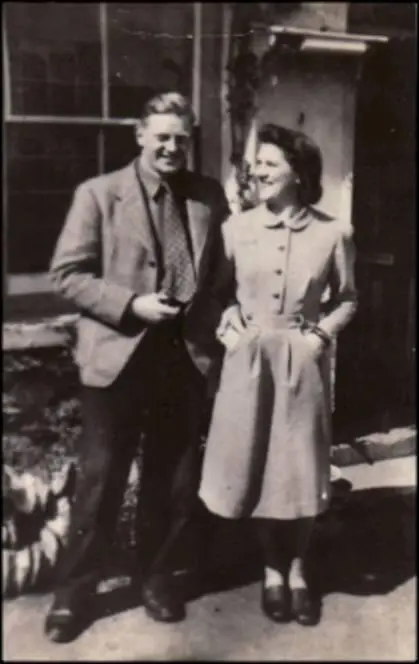

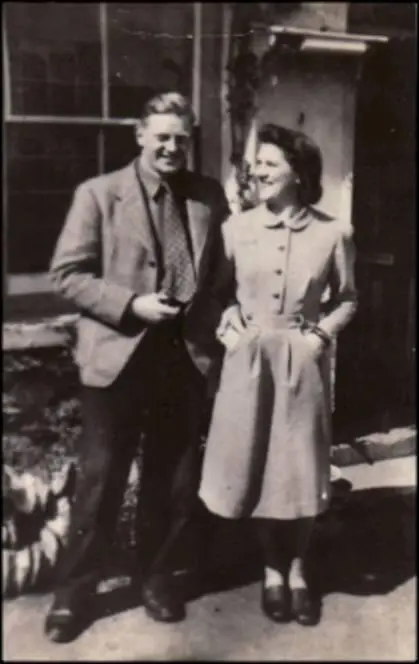

When the real-life Mary became engaged again, to my grandfather David in the blackout of 1941, her engagement ring had nine diamonds — one for every time they had met. Days later David boarded a troopship for Malta and they didn’t meet again for more than three years. Theirs was a generation whose choices were made quickly, through bravery and instinct, and whose hopes always hung by a thread. They had to have enormous faith in life and in each other. They wrote letters in ink, and these missives might take weeks or months to get through if they made it at all. Because a letter meant so much they poured themselves into each one — as if there might be no more paper, no more ink, no more animating hand.

We still have every letter that David sent to Mary. Of her replies to him we have none at all — the whole treasured bundle of them traveled from Malta on a different ship from David’s, and halfway home they were sunk by a U-boat.

When I was beginning the project I might have said that by writing a small and personal story about the Second World War, I hoped to highlight the insincerity of the wars we fight now — to which the commitment of most of us is impersonal, and which finish not with victory or defeat but with a calendar draw-down date and a presumption that we shall never be reconciled with the enemy. I wanted the reader to come away wondering whether forgiveness is possible at a national level or whether it is only achievable between courageous individuals.

As I wrote, though, I realized I was digging an even smaller hole than that. Now I hope that readers will see the book simply as the honest expression of wonder of a little man descended from titans, gazing up at the heights from which he has fallen.

— Chris Cleave, September 2015

The first picture is of my grandfather David Hill (standing on the right) with the SAS in Algeria, 1944. The second, also from 1944, is of my grandparents David and Mary. The photo was taken by a Polish RAF officer who was sharing their honeymoon hotel.

Everyone Brave is Forgiven

For my grandparents — Mary & David, NJ & M

WAR WAS DECLARED AT eleven-fifteen and Mary North signed up at noon. She did it at lunch, before telegrams came, in case her mother said no. She left finishing school unfinished. Skiing down from Mont-Choisi, she ditched her equipment at the foot of the slope and telegraphed the War Office from Lausanne. Nineteen hours later she reached St. Pancras, in clouds of steam, still wearing her alpine sweater. The train’s whistle screamed. London, then. It was a city in love with beginnings.

She went straight to the War Office. The ink still smelled of salt on the map they issued her. She rushed across town to her assignment, desperate not to miss a minute of the war but anxious she already had. As she ran through Trafalgar Square waving for a taxi, the pigeons flew up before her and their clacking wings were a thousand knives tapped against claret glasses, praying silence. Any moment now it would start — this dreaded and wonderful thing — and could never be won without her.

What was war, after all, but morale in helmets and jeeps? And what was morale if not one hundred million little conversations, the sum of which might leave men brave enough to advance? The true heart of war was small talk, in which Mary was wonderfully expert. The morning matched her mood, without cloud or equivalence in memory. In London under lucent skies ten thousand young women were hurrying to their new positions, on orders from Whitehall, from chambers unknowable in the old marble heart of the beast. Mary joined gladly the great flow of the willing.

The War Office had given no further details, and this was a good sign. They would make her a liaison, or an attaché to a general’s staff. All the speaking parts went to girls of good family. It was even rumored that they needed spies, which appealed most of all since one might be oneself twice over.

Mary flagged down a cab and showed her map to the driver. He held it at arm’s length, squinting at the scrawled red cross that marked where she was to report. She found him unbearably slow.

“This big building, in Hawley Street?”

“Yes,” said Mary. “As quick as you like.”

“It’s Hawley Street School, isn’t it?”

“I shouldn’t think so. I’m to report for war work, you see.”

“Oh. Only I don’t know what else it could be around there but the school. The rest of that street is just houses.”

Mary opened her mouth to argue, then stopped and tugged at her gloves. Because of course they didn’t have a glittering tower, just off Horse Guards, labeled MINISTRY OF WILD INTRIGUE. Naturally they would have her report somewhere innocuous.

“Right then,” she said. “I expect I am to be made a schoolmistress.”

The man nodded. “Makes sense, doesn’t it? Half the schoolmasters in London must be joining up for the war.”

“Then let’s hope the cane proves effective against the enemy’s tanks.”

The man drove them to Hawley Street with no more haste than the delivery of one more schoolmistress would merit. Mary was careful to adopt the expression an ordinary young woman might wear — a girl for whom the taxi ride would be an unaccustomed extravagance, and for whom the prospect of work as a schoolteacher would seem a thrill. She made her face suggest the kind of sincere immersion in the present moment that she imagined dairy animals must also enjoy, or geese.

Arriving at the school, she felt observed. In character, she tipped the taxi driver a quarter of what she normally would have given him. This was her first test, after all. She put on the apologetic walk of an ordinary girl presenting for interview. As if the air resented being parted. As if the ground shrieked from the wound of each step.

She found the headmistress’s office and introduced herself. Miss Vine nodded but wouldn’t look up from her desk. Avian and cardiganed, spectacles on a bath-plug chain.

Читать дальше