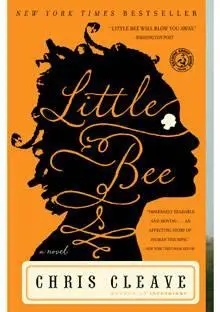

Copyright © 2008 by Chris Cleave

Britainis proud of its tradition of providing a safe haven for people fleeting [ sic] persecution and conflict.

– from Life in the United Kingdom: A Journey to Citizenship (UK Home Office, 2005)

MOST DAYS I WISH I was a British pound coin instead of an African girl. Everyone would be pleased to see me coming. Maybe I would visit with you for the weekend and then suddenly, because I am fickle like that, I would visit with the man from the corner shop instead-but you would not be sad because you would be eating a cinnamon bun, or drinking a cold Coca-Cola from the can, and you would never think of me again. We would be happy, like lovers who met on holiday and forgot each other’s names.

A pound coin can go wherever it thinks it will be safest. It can cross deserts and oceans and leave the sound of gunfire and the bitter smell of burning thatch behind. When it feels warm and secure it will turn around and smile at you, the way my big sister Nkiruka used to smile at the men in our village in the short summer after she was a girl but before she was really a woman, and certainly before the evening my mother took her to a quiet place for a serious talk.

Of course a pound coin can be serious too. It can disguise itself as power, or property, and there is nothing more serious when you are a girl who has neither. You must try to catch the pound, and trap it in your pocket, so that it cannot reach a safe country unless it takes you with it. But a pound has all the tricks of a sorcerer. When pursued I have seen it shed its tail like a lizard so that you are left holding only pence. And when you finally go to seize it, the British pound can perform the greatest magic of all, and this is to transform itself into not one, but two, identical green American dollar bills. Your fingers will close on empty air, I am telling you.

How I would love to be a British pound. A pound is free to travel to safety, and we are free to watch it go. This is the human triumph. This is called, globalization. A girl like me gets stopped at immigration, but a pound can leap the turnstiles, and dodge the tackles of those big men with their uniform caps, and jump straight into a waiting airport taxi. Where to, sir? Western Civilization, my good man, and make it snappy.

See how nicely a British pound coin talks? It speaks with the voice of Queen Elizabeth the Second of England. Her face is stamped upon it, and sometimes when I look very closely I can see her lips moving. I hold her up to my ear. What is she saying? Put me down this minute, young lady, or I shall call my guards.

If the Queen spoke to you in such a voice, do you suppose it would be possible to disobey? I have read that the people around her-even kings and prime ministers-they find their bodies responding to her orders before their brains can even think why not. Let me tell you, it is not the crown and the scepter that have this effect. Me, I could pin a tiara on my short fuzzy hair, and I could hold up a scepter in one hand, like this, and police officers would still walk up to me in their big shoes and say, Love the ensemble, madam, now let’s have a quick look at your ID, shall we? No, it is not the Queen’s crown and scepter that rule in your land. It is her grammar and her voice. That is why it is desirable to speak the way she does. That way you can say to police officers, in a voice as clear as the Cullinan diamond, My goodness, how dare you?

I am only alive at all because I learned the Queen’s English. Maybe you are thinking, that isn’t so hard. After all, English is the official language of my country, Nigeria. Yes, but the trouble is that back home we speak it so much better than you. To talk the Queen’s English, I had to forget all the best tricks of my mother tongue. For example, the Queen could never say, There was plenty wahala, that girl done use her bottom power to engage my number one son and anyone could see she would end in the bad bush. Instead the Queen must say, My late daughter-in-law used her feminine charms to become engaged to my heir, and one might have foreseen that it wouldn’t end well. It is all a little sad, don’t you think? Learning the Queen’s English is like scrubbing off the bright red varnish from your toenails, the morning after a dance. It takes a long time and there is always a little bit left at the end, a stain of red along the growing edges to remind you of the good time you had. So, you can see that learning came slowly to me. On the other hand, I had plenty of time. I learned your language in an immigration detention center, in Essex, in the southeastern part of the United Kingdom. Two years, they locked me in there. Time was all I had.

But why did I go to all the trouble? It is because of what some of the older girls explained to me: to survive, you must look good or talk even better. The plain ones and the silent ones, it seems their paperwork is never in order. You say, they get repatriated. We say, sent home early. Like your country is a children’s party-something too wonderful to last forever. But the pretty ones and the talkative ones, we are allowed to stay. In this way your country becomes lively and more beautiful.

I will tell you what happened when they let me out of the immigration detention center. The detention officer put a voucher in my hand, a transport voucher, and he said I could telephone for a cab. I said, Thank you sir, may God move with grace in your life and bring joy into your heart and prosperity upon your loved ones. The officer pointed his eyes at the ceiling, like there was something very interesting up there, and he said, Jesus. Then he pointed his finger down the corridor and he said, There is the telephone.

So, I stood in the queue for the telephone. I was thinking, I went over the top with thanking that detention officer. The Queen would merely have said, Thank you, and left it like that. Actually, the Queen would have told the detention officer to call for the damn taxi himself, or she would have him shot and his head separated from his body and displayed on the railings in front of the Tower of London. I was realizing, right there, that it was one thing to learn the Queen’s English from books and newspapers in my detention cell, and quite another thing to actually speak the language with the English. I was angry with myself. I was thinking, You cannot afford to go around making mistakes like that, girl. If you talk like a savage who learned her English on the boat, the men are going to find you out and send you straight back home. That’s what I was thinking.

There were three girls in the queue in front of me. They let all us girls out on the same day. It was Friday. It was a bright sunny morning in May. The corridor was dirty but it smelled clean. That is a good trick. Bleach, is how they do that.

The detention officer sat behind his desk. He was not watching us girls. He was reading a newspaper. It was spread out on his desk. It was not one of the newspapers I learned to speak your language from- The Times or the Telegraph or The Guardian. No, this newspaper was not for people like you and me. There was a white girl in the newspaper photo and she was topless. You know what I mean when I say this, because it is your language we are speaking. But if I was telling this story to my big sister Nkiruka and the other girls from my village back home then I would have to stop, right here, and explain to them: topless does not mean, the lady in the newspaper did not have an upper body. It means, she was not wearing any garments on her upper body. You see the difference?

Читать дальше