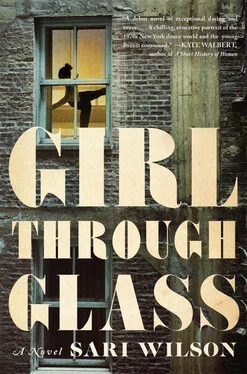

Sari Wilson

Girl Through Glass

For Josh,

from the beginning

The Beautiful is a manifestation of secret laws of nature, which, without its presence, would never have been revealed.

— JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE (1749–1832)

The garbage bags pile high on the sidewalks. The city shudders and heaves under the heat. The newspapers are filled with accounts of people being shot at night in darkened cars. Pride at New York City having its very own serial killer competes with the fear of going out after dark. At bus stops, children wearing keys around their necks—“latchkey” kids they are called — wait alone.

There is an infestation of bluebottle flies whose bug-out eyes see everything. They are poisoned to death in a citywide public health campaign, but barrelfuls of pigeons die too and their rotting corpses have to be stepped over while crossing the streets.

The sprinkler systems in the city parks break and, due to lack of funding, go unrepaired. Throughout Brooklyn the fire hydrants are decapitated and a barrage of water spouts forth. The children splash in the gutters with the pigeon corpses and dried Popsicle sticks and Twinkie wrappers, while the grown-ups stumble around, cursing and trying to drag them out.

Then there is the day in July when the lights go out. Block after block blinks off. Fans and air conditioners stall. Under the purple haze, people gather on street corners, in hallways, and in parks, around battery-powered boom boxes. A citywide blackout.

Thousands of ladybug eggs hatch in the Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s suddenly warm storage freezer. In the days afterward, they blanket Brooklyn’s parks and apartment windowsills. Then come the reports of looting and, up in the Bronx, of fierce fires in abandoned buildings. The people lock their doors and swear at the heat and pray for their city. The grown-ups are busy with the untenable state of their lives. Perhaps they feel relief at the darkness. It is the children who stand and watch their city extinguish like a dying flame.

When the ladybugs die, they fall to the grass, the floor, they crunch underfoot. They choke up vacuum cleaners. When the cool air comes, their husks are blown under piles of leaves, and, unheralded casualties of the ever-changing season, begin their descent into the earth.

Inside the world of asphalt and concrete, there is another world. Things that look like they are made by someone’s hands: grosgrain ribbons and spiderweb-thin hairnets and soft leather slippers. Down the crumbling school corridors and cracked sidewalks, these delicate things can be carried like talismans in jeans pockets or book bags.

In this other world, the girls do not wear tight jeans, scuffed Keds, or stiff pleated skirts that come in cellophane wrappers. Instead, they wear tights that range in color from a soft pink to a bright salmon. They wear cap sleeve or tank top black leotards with bands of two-ply elastic around their waists. They wear ballet slippers: Capezios, which are a tawny, russet-pink, with soles that crack in the middle of the arch, making it look like their pointe is better than it is, or orange-pink Freeds, which are made in England — and have an aura of exoticness. The poor or oblivious girls wear Selba’s, which are a flat pink that looks both prissy and cheap.

These girls — known to each other as “bunheads”—wear their hair braided or twisted and wrapped around to form a solid nub held in place with bobby pins and a hairnet. As bunheads, they each own a few prized hairnets of human hair, so soft and fine that they hold their breath while handling them; they pull the bobby pins out carefully, fold the nets into small balls of fur, and slip them back into their paper pouches. The mothers keep these pouches in their purse pockets — so expensive are they. Meanwhile, nylon hairnets from Woolworth’s shift around the bottom of the girls’ book bags while they are in the other world, catching on pens, the corner of books. The girls turn them round and round, searching for an unripped section.

In the whitewashed, cinder-block viewing room on the basement level of the new arts center, I take off my wool jacket. I smooth my black sweater dress, spray my hair to keep down the frizz, put on lipstick. I change into my heels. I load today’s DVD behind the lectern and set up the viewing for the day. Today we’re watching Le Sacre du Printemps . Of course they have already read all about it. They think they know it — Stravinsky’s famous Rite of Spring —of course, everyone knows it. But few have actually seen it.

This is Dance History 101, first viewing section of the week. The students are a standard representation of the usual dance majors and minors, with a sprinkling of theater majors. Of the dance majors, there’s two-thirds of the “dance cabal,” the rotating group of students most devoted to dance at the moment, a showing from the contact improv crew, a few former bunheads who, despite their ripped jeans, piercings, and asymmetrical haircuts have not shed their romanticism or rigidity, and one kid who drives to Cleveland to take hip-hop class, since this department is modern-based, with a lineage that runs back to the 1960s.

They enter with a scuffle of backpacks and scrape of tin water bottles, these students whose style now resembles backwoods backpackers. They pull their laptops covered in stickers out of their rucksack-size bags. And, as an afterthought, their books, which they keep on their laps because there’s no room on their desks. I’ve stopped trying to form chair circles. Whose idea was it to put wheels on these chairs? I wait for the chairs to settle into formation. Today it’s a kind of a star-shaped cluster.

The DVD starts. Here is the opening of Le Sacre —fierce tableaus of people in bearskins and Roman sandals. A set of pointy trees, a round and ruthless sun. Their movements stab and jab and rush along with the thunder and jolt of Stravinsky’s score. Halfway into the piece the group parts and reveals the shimmering awkward girl, the sacrificial lamb. She dances her strange stiff-limbed expressionless solo. Ostensibly it’s the story of the ritual pagan sacrifice of a young woman who dances herself to death, but the choreography tells another story.

She strikes out, scours the stage with extended limbs, pushing back her attackers. She’s not cowering, but filled with rage at her fate. She’s not a lamb at all. At the final discordant climb of the shattering music, the group rushes toward her and raises her high above them, and it feels like a victorious moment. But a victory of what?

The students — I check their faces in the dimness — keep looking down or picking at the stickers on their laptops. When it’s over I raise the lights. “Wow. Intense,” they say. But how to unpack it, to illuminate it?

Michael, one of the cabal this year, jumps right in. “I mean really . Compare it to what we saw last week, all those tutus and girls in white and wailing violins”—the class laughs—“but if you think about it, it has the same, I mean the same exact themes as those Romantic ballets— La Sylphide. You know, the girl, the mad girl who loses her mind and dances herself to death. . because she is too innocent or whatever—”

I nod. “Okay. But consider — you’re used to seeing ballerinas in tutus, sylphs, fairy tales lit by oil lamps, and now you are going to the theater — it’s 1913—and you are seeing this . How would it surprise you? Would it astonish you? Remember the title of our reading—‘The Age of Astonishment.’”

Читать дальше