Hannah gives Laura’s mother a stony stare. Laura’s mother touches her hair self-consciously and turns. Laura’s mother can’t really yell at the older girls. They are the linchpins of this world.

“Come on,” Hannah says.

The older girls brush by Mira and Val, Laura’s mother, and the other girls and mothers, with a swish of their warm-up pants and the clunk clunk of pointe shoes against the floor, swaying under the weight of their giant dance bags. When they have passed through, a hush follows.

To Mira and Val, Laura’s mother says, “Have some respect, would you? Go play outside in the hallway.”

But even if Mira’s mother were here, she wouldn’t care. Her mother ties ribbons in Mira’s hair when she remembers, and then they loosen, droop, and fall out, and her mother doesn’t even notice. And now, with her father gone, she is even more distracted. In her red kimono or rotating sets of overalls, she is transforming the living room with stuff she carries down from the junk room.

“ One, ” her mother sings, “ singular sensation, ” as she walks upstairs with a beaded lamp shade she commandeered from somewhere in the house. The living room begins to fill up with big plants, throw pillows, and low soft-glow lamps that perch on the floor like sleepy cats. Ashtrays appear, too. Her father hates smoking.

If only her mother were wailing in the kitchen by the dim light of one bulb, red-faced, tragic and beautiful, Mira would understand. But her mother seems almost cheerful. She seems to have more energy. Her mother zips up and down the stairs, carrying objects from one part of the house to another, loudly humming show tunes Mira didn’t know she knew.

One night when Mira was much younger, she is awakened by her parents coming home giggling. In the morning, they stand with steaming coffee in their hands in their apartment’s tiny kitchen, and with their faces flushed, they keep breaking up in laughter. Rachel’s laugh is a skittering, uneven thing that can’t seem to stop. Mira’s father’s is a full, throaty laugh that makes Mira nervous. He is normally reserved.

Her mother does most of the talking. “We’ve bought a house!” she says. “A Victorian house!” The house had been owned by the same family for generations. Some of the rooms upstairs have not been used for decades, Rachel says. They are filled with furniture — lamps, spinning wheels, moth-eaten couches. The elderly brothers who now live there are moving to a small condominium in Florida; what do they need with three floors’ worth of dusty Victorian furniture? They’ve offered her parents all the furniture in the house for one dollar. One dollar! With some reupholstering and repairs, it is probably worth a fortune. How can they refuse? As they speak, her mother uses words she has never heard before: parlor, foyer, banister, wrought iron, parquet.

When her mother is finished, her father clears his throat and smiles his shiny-penny smile. “It’s a good investment,” he says finally.

The new house, a clapboard from the 1850s, is in a neighborhood that people describe by telling you about all the famous people who used to live there a hundred years ago. The old slate sidewalks crack and buckle. The rain gutters are full of Q-tips and cellophane. Plastic bags hang in the spindly trees. Sneakers garland the telephone wires. Chunks are missing from the stone stoops in front of the houses.

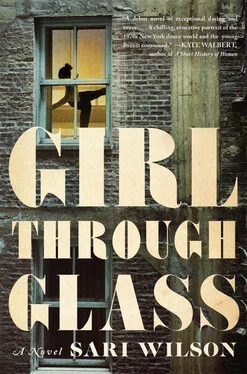

Their new house is on the edge of this neighborhood, in the middle of an especially cracked-pavement block. The block ends at an elevated overpass where you can feel the scrape and roar of the highway beneath you. It is a sad, old building with dark windows, sandwiched between two similar houses. An old ladder leans against the front, and, in the open pit behind the fence, there is a sawhorse, scrap wood, cement bags. The first time they pull up in front of the house, Mira feels something fall in her chest. “It smells gross,” Mira says, when they are inside the dank front hallway. Neither Rachel nor her dad responds. The wallpaper in the hallway is coming loose in places and flops down in strips. From the ceiling, wires dangle from holes. The house needs stripping, painting, wiring, new plumbing.

In the beginning, they all live on the first floor, which is the only habitable one. Mira moves up to the second floor while it is still under construction, where her father, after work, still in his shirt and tie, attacks the imperfections of the old house’s walls. For a time, Mira falls asleep at night to the swish and scrape of the planer, believing that this frantic, willful energy is enough to build a sturdy-walled version of reality, to keep the fairy tales at bay. In the dark, at night, in bed, Mira strains her eyes at the strange shapes the close moonlight makes against the walls half-scraped of their wallpaper. It is a form of prayer, this staring, this hoping, this squinting. She listens to the sounds of the house, the creaking and groaning, the words between her parents, high and angry, low and sweet. She imagines her parents singing a song she once heard at a Broadway play her grandmother took her to, their bright eager faces and open mouths. It makes her feel calmer to imagine this song, her parents singing it.

She has just started taking ballet at The Little Kirov, and she thinks often about the little room around the corner from the older girls’ classroom, where the costumes are stored for the annual performance of The Wounded Prince . In early December the costume room will be opened and the dusty tutus hung by color, in descending size order, will be shaken off, their synthetic tulle fluffed, and the girls who were the Pink Girls last year will become the Blue Girls, the Blue Girls become the Yellow Girls, the Yellow Girls become the Flower Girls. She does not know what the Flower Girls become. And then there is the Flower Princess — there is only one Flower Princess. She wears a long dress and garlands of flowers pinned in her hair. She wears the most diaphanous white gown and tiara and, when all the action on the stage stops and turns to her, she must do the longest, slowest, most beautiful penché, and stretching out her arm, still deep in an arabesque, with her wand touch the Prince’s lame leg. .

But time goes by and the house is not fixed. She doesn’t know whom to blame for this — her mother, her father, or the house itself. Her parents still recline after dinner on chairs that creak and groan. They sip wine. When the caning finally snaps, the broken chairs are stacked in the corner, one on top of the other. These chairs can only be salvaged by certain old-time craftsmen — weavers, caners, upholsterers — whom Rachel hunts for by going in and out of antique shops, with a little notebook in which she has sketched the broken furniture. Soon, though, she has to take a break. They go to Chock full o’Nuts, where Rachel orders Mira a cream cheese on raisin bread sandwich, sips her coffee, and thumbs through her notebook, still blank of names. Her father pulls down another chair from the rooms upstairs. They still giggle as they look around the room, flush with their own bold visions. But, as the years go by, their efforts disappear into the house like the pennies and nickels thrown in a deep wishing fountain.

IRRECONCILABLE DIFFERENCES

It’s over a month since her father left. In her red kimono, her mother plays game after game of solitaire at the table in the parlor. “He isn’t coming back,” she says. She doesn’t take her eyes off the cards. “It doesn’t mean he doesn’t love you.” Then she says some other words meant for Mira not to understand: irreconcilable differences, separation by consent . In response, Mira has her own words. “You said you loved him! You lied!” Rachel’s face is set in stone. “This really has nothing to do with love.”

Читать дальше