The clerk had already rung through her credit card. “Do you want me to void this transaction?”

“Forget it,” I said.

We continued on our way, through a crowd outside a velvet-roped place on Ninth Street. Viktoria looked at her watch. “What are these losers doing out so early? It’s not even eight o’clock! Remind me to tell you about that place one day. Crazy story!” As we passed the crowd, I noted the slight shift in Viktoria’s gait, taking on a bitchy catwalk.

As we approached the corner where I would have to turn left and she would have to turn right — trying to work out in my head how to land the good night kiss, practicing it, visualizing it — Viktoria invited me over for dinner and a movie.

“It’s my turn to cook for you. And by cook I mean order pizza. My treat. It’s what normal people do, right? They order pizza. They don’t snort coke off a guy’s asshole on a dare. Not me, a friend of mine. Logistically, it’s hard to picture. But he swears it happened, and I believe him. He’s a crazy motherfucker.”

She dialed ahead for the pizza. We took our time at the video store. We chose a Hollywood drama about recovering alcoholics and watched it while we waited for the food to arrive, listening to her puppy yap in the kitchen. When the delivery man appeared, I paid and brought the box into the kitchen and put two slices on a pair of new plates. She played with hers but didn’t eat it. When I asked she said, “I don’t really like pizza.”

“But you suggested it!”

“I was thinking about what normal people eat.” This would become a common refrain for her, what normal people did or did not do.

Neither of us was really paying much attention to the movie. She kept turning the volume down, inexplicably, whenever she would scream at the dog. “Shut! The! Fuck! Up!” she would scream, and then pick up the remote and turn it down a few notches.

She lit a cigarette and went over to the window. I joined her. She said, “I used to only smoke a couple cigarettes a day, but at rehab that’s all everyone ever does, is smoke. So now I’m up to two packs a day. It’s sick.” We finished our cigarettes, stubbed them out on the sill, and tossed them out the window. She said, “I need to take things very slow. Do you think you handle that?” It was something she had said on our first date as well. I said I could take it slow. “Good,” she said and squeezed my hand.

We went back to the sofa and watched as the film drew inaudibly toward its conclusion, which clearly was imminent because the main character had hit rock bottom and seemed to be in the middle of a teary reunion with an estranged son. Viktoria leaned against me, and as the credits rolled, we kissed. Her face smelled like peach candy. The television screen, once the credits ended, bathed us in blue. We went on kissing for a while like this. I reached into her shirt and unhooked her bra. I brushed my thumb against her nipple, back and forth, until it became firm. Her eyes were closed, her breath a string of sighs, one after the next. She did not stop me, and the dog, miraculously, was quiet except for some scrabbling now and then at the gate, a stray whimper. With my other hand I felt my way along the long path of her leg, up the inside of her thigh, and into her skirt. I reached into the humid warmth of her underwear, then reached up farther, with two fingers, and held her like this, my palm against her bristly mound as she rocked herself to climax.

We lay there for some time afterward, and from the way her head was turned, away from me, I could tell I had gone too far. I got up to pee, and when I came out, she was in a pair of boy’s pajamas. Without saying good night she went to her bedroom and closed the door.

I let myself out silently, so as not to disturb the dog.

It had been the summer of The Blair Witch Project , and after three solid months of sold-out shows and lines out the door, the moviegoing public seemed to have awoken from the hype of this little “gem” feeling swindled and took a pass on the fall season. I sat on the glass popcorn display case cross-legged, watching over the empty theaters while the other ushers engaged in closing duties ahead of schedule in anticipation of an early night. The person in the ticket booth, entirely against policy, turned off the marquee lights and lowered the gate partway so that we would appear closed to those who might be considering a late show. This rarely worked. Either a manager would catch us or someone with a Moviefone ticket purchased ahead of time would foil our plans, but tonight it worked, and I found myself back home by nine fifteen. My mother was up watching television, and I sat with her awhile. This activity had gotten to be tricky, as I had to fake a sense of continued enthusiasm for every bit of my day that I chose to relate.

My mother wasn’t fooled, of course. “I spoke with Ann today.”

“My ex-girlfriend?”

“Brody. Down the hall?”

“Right.”

“Her daughter’s looking to take up the piano. I told her that you might be interested.”

“In what? Giving lessons?”

“I didn’t say you would, I just said you might be interested. I thought it could be a nice opportunity for you.”

I was still momentarily stuck on my mistaken impression that my mother had been talking to my ex-girlfriend about me and what that conversation might have been like. There was a lot they agreed on, namely that I couldn’t be trusted to make career decisions and that I needed to shave more often.

Seeming to read my mind, my mother said with a sidelong glance, “I don’t know about this in-between look you’ve got going. Either grow a beard or don’t, but this just makes you look like you forgot to shave.”

“I did forget to shave.” I pointed the remote at the television and notched up the volume on an episode of Law & Order . I could sense her continuing to watch me as I pretended to watch the screen.

During the commercial she said, “Give it some thought. It would be some steady pocket money for you and a way for you to reconnect a little with your music, which might not be the worst thing in the world.”

“Mother dearest,” I said, turning to her and taking her hand. “I love you and have nothing but gratitude for the twenty-odd years you’ve sheltered me—”

“Uh-oh.”

“—but I think the time has finally come for me to move out.”

“Again.”

“For good this time.”

“Any place you find, you know, is going to want first and last. Even a sublet.”

“I’ll figure it out.”

I stood, gathered my mother’s dirty plates from the coffee table, and went into the kitchen. I rinsed the dishes and set each on the rubberized-wire drying rack. “Bring the box of cookies on your way back,” my mother called. “They’re on the windowsill!”

Back in my room, I got into my pajamas, a gift from An way back when. I used to sleep naked, but she claimed the oil and sweat I secreted required her to launder the sheets too often. An liked things clean. I would find my pajamas washed and folded every few days on my pillow. They were falling apart now from so many washings, the waistband losing its elastic, threadbare, the cuffs coming unhemmed. I could sleep naked nowadays if I wanted to, but I’d come to see it her way.

My mother stopped in later to return the book I’d lent her.

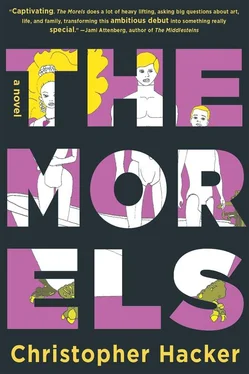

“What’d you think?”

She turned it over in her hands. “This was that boy you knew from Morningside Conservatory? What a terrible thing, doing that onstage. So destructive. I don’t know. What did I think? It’s hard, knowing nothing else about him but this book and that performance, to avoid trying to link them somehow.”

“What do you mean?”

She took a seat on the piano bench, leaned her elbow on the closed lid. “It feels very personal.”

Читать дальше