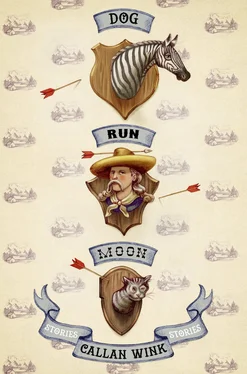

He laced up his shoes in the dark, the house silent. He drank a full glass of water and then closed the door behind him quietly. He hit the sidewalk, his legs nearly twitching with pent-up energy. He was going to fly through this run, and then get another quick half hour of studying in before the test time. He was going to kill the goddamn test, and then his life was going to unfold in a solid, meaningful way with Jeannette, kids and all. You never can tell, he thought. You can’t predict these things.

The sun was starting to come up over the hills just outside of town. He was cruising down the river path now, breath coming easily, occasionally reaching out to brush his fingers over the deep furrows of the cottonwoods that lined the trail. Just before the 9th Street bridge, there was something — a blur on his periphery — a figure in a hooded sweatshirt holding something, coming at him in mid-swing, a stick, a bat. And then Dale was running, but his feet weren’t on the ground. Fog creeping in off the river, black fog, and Dale plunging right into it.

—

Ken hadn’t gone to coffee with the guys in a long time. He didn’t know if he was up to it or not, but he had to get out of the house someway. Last night the leaves had been blasted from the trees in one brutal windstorm. He’d gone to bed and woken up to bare limbs. Clouds forecasting snow. It had been months since he’d come down to the Albertsons like this. He went to the self-serve kiosk and got his paper cupful, pushed fifty cents into the slot in the counter. He sat down at the table, and Greg Ricci, who’d been talking, barely broke stride. He nodded at Ken. “And then I told him, I says, you have to premix the damn oil and gas. I knew this kind of stuff when I was a little kid, and this is a guy with a college education. He’d never mixed up oil and gas for a lawnmower in his whole life. I don’t know. It’s a changing world. I’m sometimes glad I’m on my way out of it.”

“Oh, hell.”

“I’m serious. You go to a bar and no one’s talking to each other. Everyone’s looking down at their phone, or whatever. I went down to Denver to see my kid. I was in the airport. The bars in the airports have all got those damn iPods. Right in front of the stool so you can’t move them. I try to order a beer with the bartender and he tells me he can’t take my order. I have to punch it in on the iPod. I says, what the hell are you standing back there for then, if you can’t take my order? And he says, well, someone still has to twist the top off it, and I says, well, watch your ass because they’ll figure a way to get around that too.” He stopped to take a sip of his coffee. “How you been, Ken?”

“Okay, considering.”

“I hear you. Nice to see you.” Nods all around.

“Yep. A bit blustery this morning.”

“No shit. My old lady is going to be on me to start raking.”

“Goddamn raking.”

“Hell with it, this might be the year I pay someone to do it.”

“Oh, bullshit, you’re too much of a tightwad.”

“We’ll see. Hey, I saw the bench they put up on the river trail for your boy, Ken. Looks like they did a real nice job.”

“It’s just a bench.”

“I know. But it’s in a good spot there. A person could sit there in the shade and see the river.”

“I don’t even know who came up with that idea. I had nothing to do with it.”

“I think it was the folks at the fire department. The other paramedics down there.”

“They never asked me.”

“Well, it’s a real nice bench. There’s a plaque and everything.”

“It’s just a bench.”

“Looks well made, though. Comfortable.”

“It’s just a fucking bench. Okay? Can we all agree on that?”

“They should have asked you.”

“We could go down there and tear the bastard out.”

“I don’t want to tear it out. It’s only a bench, and it means nothing to me. Dogs will be pissing on it long after we’re dead and buried.” Ken took a sip of his coffee. He checked to see if his hands were shaking and they weren’t. This was recent, something he’d never had to do before in his life. “You hear they’re going to start issuing wolf tags?” he said. “I think we should all go get one.”

“Kill one wolf, save a thousand elk.”

“Shoot, shovel, and shut up, that’s what I always say.”

“Goddamn right.”

—

They said that he was on his way to get her. That’s what the cops said, and she had to believe they were right. She didn’t truly think he would have harmed the boys. But who’s to say? Obviously she didn’t know him anymore and maybe she never had. She’d been saved by a traffic stop of all things. He was driving too fast through the park, and when the trooper hit his lights, Tony had sped up going the other way. He was going almost eighty, they said, when he hit the berm along the river. His car came up and over and landed in the water upside down.

Sometimes in the early morning she came awake with the feeling that a hand was on her hip, a male presence at her back. If she was still half asleep she might remember the dream she was having. Sometimes it was Dale, kind and considerate and serious, and when this was the case she woke up sad. Sometimes it was Tony, the old Tony, the one who knew her better than anyone, and on these occasions she woke up flushed and hating herself.

After it happened, weeks after the funeral, she stopped by Dale’s father’s house. She brought him a pan of lasagna. He stood in the doorway. Made no move to let her in.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I don’t know what to say.”

“There’s nothing to be sorry about,” he said. His eyes saying just the opposite. “I’ll bring your pan back to you tomorrow,” he said. “And I’d appreciate if you never did anything like this again. I’d just as soon you didn’t.” He shut the door carefully and Jeannette walked home. She had to sit on the front steps for a long time before she’d found a face she could present to her sons.

—

They’d gotten a big snow overnight and school was canceled. Their mom had stayed home from work and made them hot chocolate. His little brother had the hot chocolate, but he told her he’d rather have coffee. He made sure she did it correctly, five scoops. He put a lot of cream in it and sugar and a little hot chocolate too and that was pretty good. They sat drinking in the kitchen watching the flakes come down fat and white as the pom-poms on a Christmas hat.

“Let’s get all our warm stuff on and go out to the park,” his mom said. It was her cheerful voice, the one she used a little bit before but seemed to use a lot now.

He shrugged.

“We could build a snowman,” his little brother said.

His mom was stirring her coffee. “That sounds like a good idea,” she said. “Let’s do it.”

On the way to the park, someone passed them on skis, going right down the middle of the street. The trees were coated in a thick, white blanket, the pines with their branches weighted down and sagging, so that if he bumped them they’d shed their load and spring up in a shower of fine crystal.

They made a snowman, but they hadn’t thought to bring a carrot for a nose or coal for eyes, so they just used sticks but it didn’t look quite right. He and his brother karate-kicked its head off.

He got the idea that he might like to build a snow fort. Kind of like an igloo, but also with some sticks, like a tipi. He enlisted his brother’s help. His mother helped for a while, too, but then she said she was tired and went to sit on a bench. There were some trees over there, and he could just see the river behind her. She was wearing a bright-red Livingston Fire Department hat that used to be Dale’s, and he had the thought that if snowmen had blood, their insides would look like a cherry snow cone.

Читать дальше