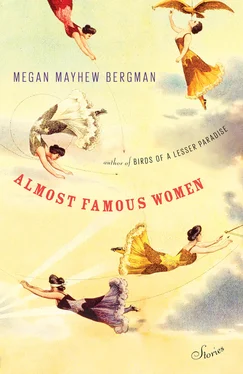

Megan Mayhew Bergman

Almost Famous Women: Stories

’Tis the white stag, Fame, we’re a-hunting,

bid the world’s hounds come to horn!

— EZRA POUND

You can fill up your life with ideas and still go home lonely.

— JANIS JOPLIN

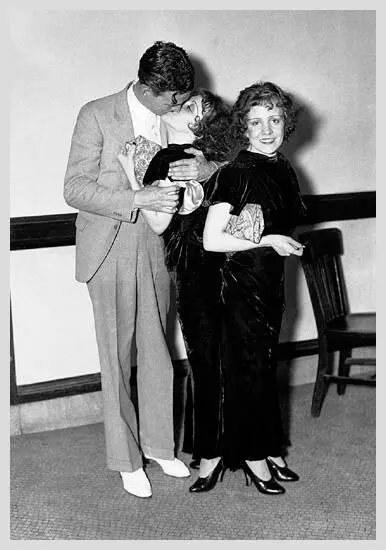

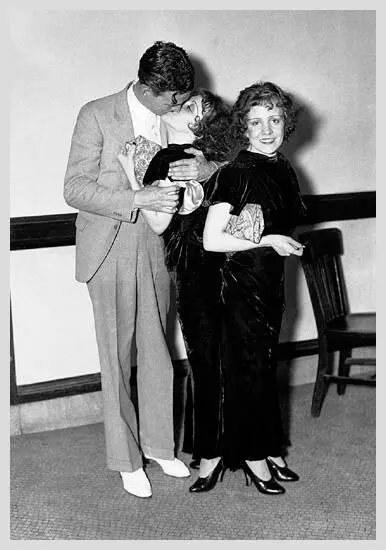

New York denies Violet Hilton, pictured with Daisy, a marriage license, on the grounds that it would be illegal to issue the license to two persons (1934).

Associated Press photo, July 5, 1934. Reprinted with permission.

THE PRETTY, GROWN-TOGETHER CHILDREN

Let me tell it, I said.

No, you’re a liar and a drunk, she said. Or I said.

Our voices could be like one. I could feel hers in my bones, especially when she sang — a strong quicksilver soprano. We were attached at the hips and shared blood, but no vital organs. Four arms, four legs — enough to make a man give a second look.

One of us has to tell it, I said, and it’s going to be me.

An agent had come to see us. Or that’s what he claimed to be. A talent scout. I couldn’t remember his name. He wore a blue sports coat with heavy gold buttons, jeans, loafers. His hair shone with tonic, and he knew how to shake hands. My bones ached from his grip.

Look, I said to Violet. I’m a better storyteller than you. You sing, I tell stories.

Violet didn’t answer. She’d vanished, the way the great Harry Houdini had taught us to do in the RKO Studios cafeteria. When you’re tired of each other, he’d said, imagine retreating into an imaginary shell. A giant conch. Harry was short and bowlegged. His curly hair splayed across his forehead into a heart shape. Separate mentally , he’d said.

What about when Daisy is indiscreet? With men? Violet had asked. What do I do then?

Same thing you’ve done in the past, I’d said. Look away.

Violet was like that. Made her voice rise when she wanted to play innocent. She pretended to be shy. But I could feel her blood get warm when she spoke to men she admired. I could feel her pulse quicken.

Back in the RKO cafeteria days, we had floor-length raccoon coats, matching luggage, tortoiseshell combs, and high-end lipstick. We had money in the bank. We took taxis. We traveled, kissed famous men. We’d been on film. The thirties, forties, even the fifties. Those had been our decades. We had thrived.

In the RKO days, people thought our body was the work of God.

But now we were two old showgirls bagging groceries at the Sack and Save in Aberdeen. There were no more husbands, no boyfriends. Just fat women and their dirty-nosed children pointing fingers in the grocery line.

Can y’all help us get these bags out to the car, they’d ask.

I never met so many mean-hearted women in my life. Violet and I were still able-bodied, but we were old. Our knuckles hurt from loading bags. Our knees swelled from all the standing. But we’d do it to keep our boss happy, hauling paper bags to station wagons in the parking lot.

I jes’ want to see it walk, the kids would whisper.

We lived behind the grocer’s house in a single-wide trailer with a double bed and a hot plate. Mice ran through the walls, ate holes in our cereal boxes.

Look, the agent said. I’m going to come back tomorrow and we’re going to talk about some projects I have in mind.

Come after supper, I said.

Houdini had told us: never appear eager to be famous.

The agent came closer. His cologne was fresh. He made Violet nervous, but not me. He reached for each of our hands and kissed our knuckles.

Until then, he said, and disappeared through the screen door. The distinctive sound of the summer night rushed inside. Cicadas, dry leaves rattling in the woods, a single car on the dirt road.

Some nights Violet and I sat on the cinder-block steps outside, rubbing our bare toes in the cool dirt, painting our nails. Like most twins, we didn’t have to talk. We were somewhere between singular and plural.

After the agent left, Violet and I sat on an old velour couch, turning slightly away from each other as our bodies mandated. I forgot how long we’d been sitting there. There were framed pictures of people we didn’t know on the walls. The kitchen table had three legs. One had been chewed and hovered over the linoleum like a bum foot. The curtains smelled like tobacco. The radio was tuned to a stock car race.

Rex White takes second consecutive pole.

Violet was still, hands on her knees. She was probably thinking about an old boyfriend she had once. Ed. Violet had really loved Ed. He was a boxer with a mangled face and strange ears that I didn’t care for. He wasn’t fit for a star, I told her. When she went into her shell I figured that’s who she went there with.

I was hot and dizzy. Our trailer had no air-conditioning.

Postmenopausal, I figured. I needed water.

I stood up.

Violet came out of her imaginary shell.

We have to get some money, she said, as we moved toward the sink. We have to get out of here. I have paper cuts from the grocery bags. My ankles are swollen. How come you never want to sit down?

I’m working on it, I said. Besides, we’re professionals. We’ve got something left to offer the world.

I let the faucet sputter until the water ran clear.

One of us could die, I said. And they’d have to cut the other loose.

So that’s what it takes, Violet said and disappeared into herself again.

I was told our mother was disgusted when she tried to breast-feed us.

Just a limp tangle of arms and legs. Too many heads to keep happy, Miss Hadley said. Lips everywhere. Strange cries.

Miss Hadley was our guardian. We lived with her in a ramshackle house that was part yellow, part white — an eyesore on the nice side of town. The magnolia trees were overgrown and scratched the windows. The screened-in porch was packed with magazines, rusted bikes, broken lamps, boxes of old clothes and library books.

Weren’t for me you’d be dead, Miss Hadley said. I saved you.

Like stacks of coupons and magazines — we were one of the things Miss Hadley collected, lined her nest with.

Once, when you was toddlers, you got out the door nekkid and upset the neighborhood, she said. She liked to remind us, or maybe herself, of her generosity. Her ability to tolerate .

Carolina-born, Miss Hadley looked like she was a hundred years old. Her cheeks sank downward. She had a fleshy chin and a mouthful of bad teeth.

Daisy, she’d say, I’m fixin to get after you.

And she would. She once threw a raw potato at my forehead when she found me rummaging in the pantry after dinner. Miss Hadley slapped my knees and arms with the flyswatter when I talked back. Sometimes she’d get Violet by accident.

She ain’t do nothing to you, I’d say. Leave her be.

Don’t sass me, she’d say. You’ve got the awfulest mouth for a girl your age.

When we were young, Violet and I had the thickest bangs you’d ever seen, enormous bows in our hair. There were velvet ribbons around our waists, custom lace dresses, music lessons. We were almost pretty.

We learned how to smile graciously, how to bask in the charity of the Christian women in the neighborhood. We learned to use the toilet at the same time. We helped each other with homework and chores.

Miss Hadley kept a dirty house, scummy dishes in the sink. There was hair on the floor, toilets that didn’t work, litters of rescued dogs that commanded the couch. Her stained-glass windows were cracked. The front door was drafty. Entire rooms were filled with newspapers. Her husband was dead (if she’d ever really had one) and she had no children except for us. Looking back, we weren’t her children at all. We were a business venture.

Читать дальше