When the agent comes back, I said, let’s do “April in Paris.”

Let me get you a cool washcloth, she said, lifting me gently from the couch.

Let the water run clear, I said. Tomorrow…

Trust God on this one, Violet said. Rest.

In our early days, people had trusted God’s intent. We were the way we were because He made it so.

I remembered what Ed had said that night I crushed his face. His mangled, fighter’s face.

You are not made in His image, he’d said. You can’t be.

And now, ladies and gentlemen, the tortoise race .

My eyes watered. I felt as though I could no longer stand.

I jes’ want to see it walk.

I’m sorry, I said to Violet, before I pulled her to the ground.

If we have interested you, kindly tell your friends to come visit us.

There was something about the body, our seam. Were we one or were we two?

I touched the skin between us.

One day soon, I said, you’ll walk out of here alone.

Hush, Violet said. Hush.

Get a new dress, I said. Eat all the goddamn cookies you want.

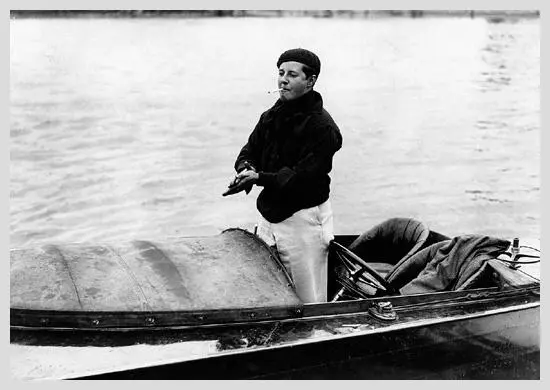

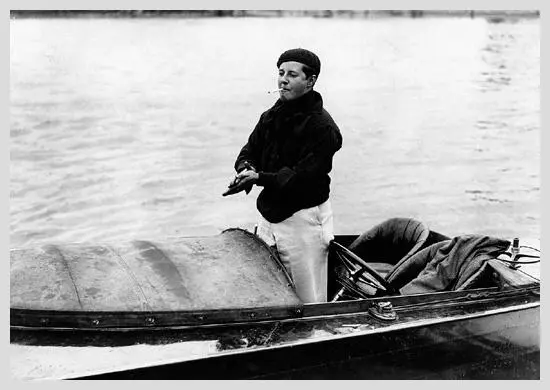

M. B. “Joe” Carstairs, the fastest woman on water.

Photo reprinted with permission of The Mariners’ Museum,

Newport News, VA.

Georgie woke up in bed alone. She slipped into a swimsuit and wandered out to a soft stretch of white sand Joe called Femme Beach. The Caribbean sky was cloudless, the air already hot. Georgie waded into the ocean and as soon as the clear water reached her knees she dove into a small wave with expert form.

She scanned the balcony of the pink stucco mansion for the familiar silhouette, the muscular woman in a monogrammed polo shirt chewing a cigar. Joe liked to drink her morning coffee and watch Georgie swim.

But not today.

Curious, Georgie toweled off, tossed a sundress over her suit, and walked the dirt path toward the general store, sand coating her ankles, shells crackling underneath her bare feet. A lush, leafy overhang covered the path, which stopped in front of a cinder-block building with a thatched roof.

Georgie looked through the leaves at the sun overhead. She lost track of time on the island. Time didn’t matter on Whale Cay. You did what Joe wanted to do, when Joe wanted to do it. That was all.

She heard laughter and found the villagers preparing a conch stew. They were dancing, drinking dark rum and home-brewed beer from chipped porcelain jugs and tin cans. Some turned to nod at her, stepping over skinny chickens and children to refill their cans. The women threw chopped onions, potatoes, and hunks of raw fish into the steaming cauldron, the inside of which was yellowed with spices. Joe’s lead servant, Hannah, was frying johnny-cakes on a pan over a fire, popping pigeon peas into her mouth. Everything smelled of fried fish, blistered peppers, and garlic.

“You’re making a big show,” Georgie said.

“We always make a big show when Marlene comes,” Hannah said in her low, hoarse voice. Her white hair was wrapped. She spoke matter-of-factly, slapping the johnnycakes between the palms of her hands.

“Who’s Marlene?” Georgie asked, leaning over to stick a finger in the stew. Hannah swatted her away and nodded toward a section of the island invisible through the dense brush, where a usually empty stone house covered in hot pink blossoms stood. Joe had never explained the house. Now Georgie knew why.

She felt an unmistakable pang of jealousy, cut short by the roar of Joe pulling up behind them on her motorcycle. As Joe worked the brakes, the bike fishtailed in the sand, and the women were enveloped in a cloud of white dust. Georgie turned to find Joe grinning, a cigar gripped between her teeth. She wore a salmon-pink short-sleeved silk blouse, and denim cutoffs. Her copper-colored hair was cropped short, her forearms covered in crude, indigo-colored tattoos. “When the fastest woman on water has a six-hundred-horsepower engine to test out, she does,” she’d explained to Georgie. “And then she gets roaring drunk with her mechanic in Havana and comes home with stars and dragons on her arms.”

“I’ve never had that kind of night,” Georgie had said.

“You will,” Joe had said, laughing. “I’m a terrible influence.”

Joe planted her black-and-white saddle shoes firmly on the dirt path to steady herself as she cut the engine and dismounted.

“Didn’t mean to get sand in your stew,” Joe said, smiling at Hannah.

“Guess it’s your stew anyway,” Hannah said flatly.

Joe slung an arm around Georgie’s shoulders and kissed her hard on the cheek. “Think they’ll get too drunk?” she asked, nodding toward the islanders. “Is a fifty-five-gallon drum of wine too much?”

“You only make rules when you’re bored,” Georgie said, her lithe body becoming tense under Joe’s arm. “Or trying to show off.”

“Don’t be smart, love,” Joe said, popping her bathing suit strap. The elastic snapped across Georgie’s shoulder.

“Hannah,” Joe shouted, walking backward, tugging Georgie toward the bike with one hand. “Make some of those conch fritters too. And get the music going about four, or when you see the boat dock at the pier, okay? Like we talked about. Loud. Festive.”

Georgie could smell butter burning in Hannah’s pan. She wrapped her arms around Joe’s waist and rested her chin on her shoulder, resigned. It was like this with Joe. Her authority on the island was absolute. She would always do what she wanted to do; that was the idea behind owning Whale Cay. You could go along for the ride or go home.

Hannah nodded at Joe, her wrinkled skin closing in around her eyes as she smiled what Georgie thought was a false smile. She waved them off with floured fingers.

“Four p.m.,” Joe said, twisting the bike’s throttle. “Don’t forget.”

At quarter to five, from the balcony of her suite, Joe and Georgie watched the Mise-en-scène , an eighty-eight-foot yacht with white paneling and wood siding, dock. Georgie felt a sense of dread as the boat glided to a stop against the wooden pier and lines were tossed to waiting villagers. The wind rustled the palms and the visitors on the boat deck clutched their hats with one hand and waved with the other.

Every few weeks there was another boatload of beautiful, rich people, actresses and politicians, piling onto Joe’s yacht in Fort Lauderdale, eager to escape wartime America for Whale Cay, and willing to cross a hundred and fifty miles of U-boat-infested waters to do it. “Eight hundred and fifty acres, the shape of a whale’s tail,” Joe had said as she brought Georgie to the island. “And it’s all mine.”

Georgie scanned the deck for Marlene and did not see her. She felt defensive and childish, but also starstruck. She’d seen at least ten of Marlene’s movies, and had always liked the actress. She seemed gritty and in control. That was fine on-screen. But in person — who in their right mind wanted to compete with a movie star? Not Georgie. It wasn’t that she wasn’t competitive; she was. Back in Florida she’d swum against the boys in pools and open water. But a good competitor always knows when she’s outmatched, and that’s how Georgie felt, watching the beautiful people in their beautiful clothes squinting in the sun onboard the Mise-en-scène.

Читать дальше