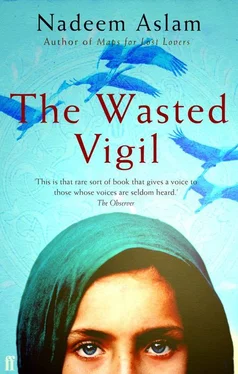

Nadeem Aslam - The Wasted Vigil

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadeem Aslam - The Wasted Vigil» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, Издательство: Faber and Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Wasted Vigil

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber and Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Wasted Vigil: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Wasted Vigil»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Wasted Vigil — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Wasted Vigil», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I can understand your reasons.’

‘People marry every day, I said to myself. It should happen once or twice every century if the purpose of marriage was to find your soul’s mate. I kept telling myself my personal happiness was not important — that I should do this to help my mother, to find my missing brother.’

From the table beside the bed she picks up the little origami shape she had folded some days ago, before David’s arrival. She turns it in her hands, something material to concentrate on.

‘As the years passed I came to love Stepan more than my life. You ask why I kept saying no. It was partly because I thought it would be bad for him to be associated with me, with us. I thought it would harm him professionally.’

‘So you weren’t completely selfish.’

Folding and refolding the paper for over a minute, she had fashioned the origami piece — a shape and a procedure that had lain unremarked-upon in her mind since her Leningrad schooldays.

‘And did things get better because of his connections?’

‘Suddenly everything was easy. It was shocking. It would make me so angry inside. I am here because of his friends in the army, because he and they began inquiries about Benedikt. But, no, to me what I did remains unforgivable. Other people managed — why couldn’t I?’

‘Your country made you feel guilty for not being able to fly. They put so much unreasonable pressure on you, so many unreasonable demands. Of course you couldn’t cope and looked for a way out.’

‘I wonder how much of it is to do with my country. Maybe it’s who I am.’

‘There’s no way of knowing such things.’

‘I knew beforehand he wanted to be a father. I kept from him my suspicions that it might be difficult for me to conceive. There were rumours that the state had had me poisoned — I had suddenly fallen ill some years earlier, during the time I was being loud in trying to find information about Benedikt. Now I was too terrified to go to the doctors, in case they confirmed my fears. I decided I would just hope for the best. In the end I did tell him, two weeks before the wedding. He said he didn’t care about anything as long as I was his wife. But he did accuse me of deception in later years.’

She places the origami on the table. Four small hoods, hinged together, to be worn on the tips of the fingers. It’s a way for children to tell fortunes, the possibilities hidden under four triangular flaps, one of which you are asked to choose. When she made it sitting beside the Buddha, she had turned over each of the flaps even though she knew nothing was written under any of them.

‘We can never know how different we could have been,’ David says, holding her close. ‘This one life is all we have.’

The afternoon is continuing out there. A faint melody from a stringed instrument drifts down from Marcus’s room. In picturing what the instrument might look like she recalls the small watercolour of a Persian lutenist in the Hermitage. Marcus said he sometimes sees music as a companion, almost a physical presence.

Pointing to a portrait on the wall he said Ziryab of Andalusia had added the fifth string to the lute in the ninth century and pioneered the use of eagles’ talons as plectra.

David’s hipbone is like a warm stone against her thigh. A sensation she has not received since Stepan’s death two Decembers ago. She had stepped away from everyone, a sleepwalker in a fog, the world ceasing to exist. On many levels she had lived Stepan’s life for so long — moving to a new city upon marrying him — and she was only slightly surprised that the withdrawal didn’t prove more difficult now. She didn’t announce her arrival back in St Petersburg to most of her friends and acquaintances, just letting the darkness increase as the months went by.

But there was a world out there. And she was jolted awake to it, to her responsibility to it, when her mother died surrounded by a dozen notebooks ’worth of thoughts, all addressed to her. Lara could not be contacted because she hardly ever answered the telephone now or responded to the knock on the door, seldom opened a letter, not wishing to be told You’ll love again . When her mother died in her sixth-floor flat the first problem for the neighbours was to get the body to the morgue. In the new Russia the men who drive the mortuary vans demand substantial bribes, don’t come for days after being called, and sometimes don’t come at all. There were stories that in the tower blocks of the very poor the despairing relatives or neighbours simply threw the corpse out of the high windows. There are always bodies in the Russian winter snow in these areas. This did not happen to Lara’s mother but there was no loved one in attendance when she was buried, and when by chance Lara arrived for a visit at her mother’s flat a fortnight later she found her notebooks scattered on the pavement. Only the first page in each was filled. The rest were blank. She hadn’t turned over a new page, had written and drawn on the same one repeatedly so that the feelings and ideas were juxtaposed onto each other, indecipherable, the way a book of glass would be, the eye having access to its depth through the overlapping layers of contents.

As the weeks passed Lara re-established contact with the friends from her youth, reaching out tentatively, reminiscing about those early days when the most important thing for them was owning a perfect smile. ‘They say the lips should rest on the line where the teeth meet the gums. And the whiteness of the teeth should match the whiteness of the eyes exactly.’ How incredible it seems that until her teens she had ridden in a car only a handful of times. She remembers the thrill, the smell of petrol on a hot Leningrad day, her beloved city with its islands and palaces and its leap-and-plunge arches, its justly loved white nights. There was the garden where Casanova and Catherine had met and talked about sculpture, and there were the cinemas where the ticket seller would for a few roubles extra sell a boy the seat next to a pretty girl.

Her dear Russia. The first boy she kissed at fifteen, the beautiful Mitya, meeting him when his mother called her in out of the street and asked to be shown how to arrange salad on a dish in a pleasing manner: the woman was giving a party and thought Lara, being young, would know about such modern and stylish things. Just called her in out of the street! Pulling her out of the pattern her life had made in the city till then. The sudden rush of blood to the head when Benedikt showed Lara and her friends that a song being played on the radio could be taped, captured on a cassette; until then they had thought you could only record music from LPs, something that cost money. But this was free and it was an electrifying discovery. Back then when everything lay ahead. A life of possibilities and discoveries. Oh the wonder of looking for the first time into one of those mirrors that magnified your face!

As they grew older they discovered that the library copy of Spartacus was missing half its pages. They learned that in the past the word ‘demos’ — the root of ‘democracy’ — had to be excised from a book on Greek antiquities, and that according to some books certain Roman emperors had not been ‘killed’ but had ‘died’ — so as not to encourage among the Soviet populace the idea of the liquidation of unwanted leaders. And, yes, Tatyana Ulitskaya’s father climbed into a bottle of vodka every night and began to swim circles in it, swallowing a layer of liquid with each lap so that he was found in the morning lying prone on dry glass. And, yes, while many of them couldn’t imagine being able to exist away from Russia, some had dreamed of moving to the West, dreamed of ease, even riches — the dollar trees that would sprout from the palms of their hands once they got there, producing golden fruit they’d store in bank vaults.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Wasted Vigil»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Wasted Vigil» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Wasted Vigil» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.