“Hidee, Miss Lamb,” Mark said, pushing his shaggy hair out of his eyes. I don’t believe I ever seen them two that they didn’t need a haircut. Mark was the only one of them boys that’d talk. I don’t reckon I ever heard Douglas say a word. Myra said he knowed how to talk, he was just real quiet. Douglas was in Myra’s class and Mark was two years ahead of her. Both of them boys was struck on Myra and tried to court her all through school, but she never would go with either one of them. Mark and Douglas was nice-looking fellers, even when they was little, had big old brown eyes and gold hair, but I reckon they seemed like brothers to Myra. They was always into something. That day it wasn’t even dinnertime yet and looked like they’d already been rolling in mud. Myra always kept right up with them, climbing trees and shooting marbles and whatever else it was they done. Mark held out his BB gun to show Myra and said, “Let’s go shoot cans.” Then they tore off up the hill ahead of me like their britches was on fire.

I took my time following them on towards the house. Bill and Oleta have a tiny little place with a stone foundation and a covered porch. Not too long ago Bill had put on some cheap gray cardboard siding, supposed to look like brick. He’d poured a cement walk up to the porch, too, but grass had growed over most of it. There was trees and bushes crowded against the house and a line of fence posts sticking up behind it where Bill kept a few cows.

Bill gets rid of his cows every few years, until he takes a notion to buy up some more, but he never does get tired of that horse he bought from a man in Dalton, Georgia. I swear that’s the orneriest creature I ever seen, but Bill loves her like somebody. Now, she’s beautiful, I can’t deny that, and you can see her spirit burning like fire in them blue eyes. She’s a paint mare, and the first time I seen them eyes I liked to jumped out of my skin. I never knowed a horse could have eyes like that. They was just like Myra’s, and that might be why my grandbaby was so fixed on her from the beginning. I knowed that was why she always wanted to go up to the Cotters’ with me, to see Wild Rose. That’s the name the horse had when Bill bought her, and it suits her. His old fence never could keep her in. I don’t know how many times Rose came tearing down the mountain with her tail up, trampling through our garden and leaving manure in the yard. Sometimes I wondered if she was looking for Myra. It was eerie seeing them together. Myra would stand at the fence and Wild Rose kept her distance, but she’d stare Myra straight in the eye, neither one of them moving a muscle. Then Rose’d take off like she was spooked across the hills. Wild as Myra was, I guess in a way them two was sisters.

When I got up to the house I could hear Douglas and Mark and Myra at the barn calling for Wild Rose, but I couldn’t see them. As I was walking up on the porch Bill Cotter opened the front door and came out. I said, “Hidee, Bill.” He tipped his cap at me and went on down the steps to his truck. Bill don’t say much, but he’s a good man.

I went in the front room and seen the linoleum needed mopping. Bill or them boys had tracked mud in. Oleta was laying on the couch and her head nearly wringing wet with sweat. Poor thing looked like she was roasting so I opened some windows for her.

“Where’s that Bill headed off to?” I asked, gathering up some pieces of newspaper he’d left by his chair.

“Laws, I don’t know. He don’t never tell me nothing. Why, he don’t even tell me bye no more when he leaves the house. Does Macon do you thataway?”

“Well,” I said, but Oleta was done off on another subject before I could answer.

There was quite a bit needed doing. I swept and mopped and put a pot of beans on the stove. As I was tidying up, somehow or other I got to feeling funny. I got to studying on what Oleta asked, did Macon do me that way. I reckon the answer would have been yes if she had give me time. He’d head out for work every morning without saying a word, but he didn’t need to. We knowed each other so good after all them years of marriage, there wasn’t no use in saying much. I’d fix his dinner and put it in his bucket and we’d drink us a cup of coffee beside of the stove, then he’d get up and leave. I didn’t see nothing wrong with it, but the way Oleta said it sounded bad. I tried to remember if I said goodbye to Macon when me and Myra left the house that morning. The whole time I was worshing Oleta’s breakfast dishes and sweeping off the back stoop I was retracing my steps, trying to decide if I told Macon bye. In my head I was waking up before first light, Macon already setting on his side of the bed getting his boots on. I was walking across the dewy grass toward the barn to gather eggs. I was frying the eggs in my old iron skillet and calling for Myra to get up before she slept the day away. I was eating breakfast in the kitchen by myself because Macon and Myra was done before I ever set down. I was bringing in some tomatoes before they rotted on the vine. I was telling Myra if she wanted to walk up to the Cotters’ with me she better come on. I was passing Macon on my way down the hill with Myra as he was headed for the barn. “Did you see them dadburn Japanese beetles on my rosebush?” I asked him. “I was fixing to spray,” he said. That was it. I never did say bye. I reckon he knowed where I was going, because he probably heard me holler at Myra, but I started feeling bad just the same.

The longer I was at the Cotters’, the more anxious I got to get back to the house. I allowed to Oleta I better get on home and fix Macon a bite of supper. I had to stand in the yard and holler for Myra a long time, until she finally came out of the woods looking like she’d rolled in the mud with them Cotter boys, sticks and leaves stuck in her hair. I thought how I’d have to check her head for ticks before she went to bed that night.

Since I’d turned seventy-one, I didn’t get around as good as I used to. I was wore out by the time we got home, but Myra never ran out of wind. She took off for the house soon as we made it up the hill and beat me to the door by a mile. She went on in while I was still dragging across the yard. I seen where Macon had done a little bit of weeding around the steps and there was a mess of wood shavings in the grass, too, so I knowed he must have been whittling. He was getting on in years hisself, nearly eighty by then, and couldn’t take the sun for long at a time. He’d take a break and set down if he got too hot working in the yard, but Macon never could stand for his hands to be idle.

I didn’t think nothing of it and went on in the house. First thing I seen was Myra, standing in the middle of the floor with her back to me, hair ribbon hanging crooked where she’d been playing. It took me a minute to see she was looking at Macon. He was slumped over in his chair, the same way he took a nap of the evenings, but it still didn’t hit me that something was wrong. I reckon I was so hot and weary my head was addled.

“What in the world are you doing?” I asked Myra.

She turned around and I never will forget the look in her eyes. She said, “Is Granddaddy sleeping?”

That’s when I knowed. I walked over to his chair and seen how still he was. “No,” I said to Myra. “He ain’t asleep.” I ran my finger across that island birthmark one more time. Then I sent Myra down to the Barnetts’ for Hacky to get word to the coroner. I hated for her to have to do it alone, but I couldn’t bring myself to leave Macon’s side.

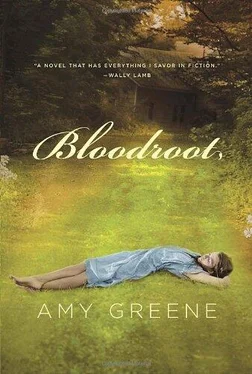

I was setting at Macon’s feet waiting for the people to come when I noticed this little wood box, about the size of my hand. It was on a piece of newspaper on the end table beside of his chair, looked like the varnish was still tacky on it. He must have been working on it for a while out in the barn when I thought he was making another bird-house. Once I seen it I smelled the varnish, but I hadn’t even noticed it until then. The lid was laying separate and it was the prettiest piece of carving I ever seen. It was carved with a bloodroot flower, all by itself. I could tell he’d took time with every petal and every vein in the leaves. I figure he made it for Myra’s birthday to hold her trinkets, and meant to hide it someplace once the varnish dried. Then he’d leave it on her pillow without saying nothing and stand off somewhere waiting for her to find it.

Читать дальше