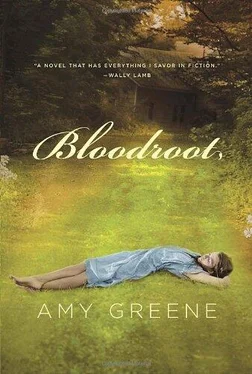

It’s true that Myra and Wild Rose are two of a kind. That’s why they took to each other so quickly. If I believed that talk I heard about witches, I’d figure Wild Rose was Myra’s familiar. But there’s one difference I can think of between them. Wild Rose never let me within arm’s reach of her, but I got away with touching Myra once. It was because of the poems. All through elementary school Myra and I had the same teachers, and in high school we always had at least one class together. Junior year it was English. Myra loved the poems we studied, especially Wordsworth. “It’s like he’s talking about here,” she said. “He wrote this one a few miles above a place in England called Tintern Abbey, but I can tell he feels the same way as I do about Bloodroot Mountain. Does that make any sense to you?” I said yes, but it didn’t matter to me. I just liked hearing her talk.

Whenever she knew that Mark was away from home, she would come walking up the mountain to find me, carrying one of her books, wearing a floppy old dress with the sun in her eyes. Just to make sure, she always asked, “Where’s Mark?” I’d smile with my lips closed over my broken tooth, knowing she needed to share the poems she loved with somebody quiet. I’d say, “Mark’s gone hunting,” or fishing, or down to the pool hall with some of his friends. Then she’d ask if I wanted to take a walk. She didn’t really have to ask. She knew I’d follow her anywhere, branches slapping my face in her wake.

Most of the time we went to a big rock high on the mountain behind her house and I’d sit there with her for hours, listening to her read. But that day we decided to walk down to the creek branch instead, where it runs downhill beside the road. She was quiet and I thought maybe she had spied an animal or bug she wanted to touch. She could track for hours, shushing Mark and me, telling us to go away, even though we never did. But there was no lizard, no squirrel or frog this time. She was only thinking.

When we came to the creek branch we crawled under the pink rhododendron together, where its low branches made a cave of shadows sprinkled with coins of light. She read for a while, but I could tell there was something on her mind. Finally, she put down her book and sat on a rock with her feet in the water. I stared at them through the silt-swirling ripples. They were long and slim, smooth on top and leathery on the bottom. “I got a chickadee to eat out of my hand,” she said, dipping her cupped palm in the water.

“How’d you do that?”

“You know that stump behind the house where Granny scatters seed? They come in droves this time of year, all different kinds of birds. I’ve been sitting there every day with my hand out. They’re used to me now.”

“Reckon they think you’re part of the stump?”

“I am,” she said.

She lowered herself off the rock and into the branch, her dress darkening and spreading in the water. She lay back on the rocks with light shifting on her face, fingers of creek water closing across her middle.

“Can I tell you something?” She closed her eyes and propped up on her elbows. The water trickled over her thighs and played with her dress tail. I couldn’t stop looking at her pale body, stretched out long and hard in the creek branch.

“Yeah.”

“I’m afraid you’ll think I’m crazy.”

“I won’t.”

“I thought… it was like …that chickadee was my mother.”

Myra had never mentioned her dead mama to me before. “Like reincarnation?” I asked. “Better not let the church folks hear you talking that way.”

Myra smiled. “Not exactly.”

“Like a ghost or something?”

“More like a spirit. Like she’s still here.”

“The Bible says there’s two places people go when they die.”

I looked at her stomach, the black dress gathering in neat wrinkles where her navel was hidden. I imagined a dark slit filling with water.

“I wonder about her. You know she moved off to town with my father when she was seventeen. I can’t figure out how she could leave this place. She must not have been like me.”

I lowered myself into the water beside Myra. The cold took my breath. “Does it make you sad?”

“Hmm?”

“That she wasn’t like you?”

“I don’t know.” Myra sounded sleepy, drunk on the feel of the creek lapping at her fingers, running like a cool scarf over her elbow bends, gliding under her heels and between her toes, and all the smells of blossoms and muck and mottled toadstools risen like yeast in the shade. Looking at her, a feeling came over me that she might do the same thing her mama had done. I wouldn’t have believed that Myra could leave the mountain, but I hadn’t seen until then how she longed for her mama and wanted to know about her.

“You’ll go, too,” I said, leaning over her.

Myra took in a deep breath, black hair coiling out in all directions, a nest of water snakes. “Never,” she exhaled, and I felt the cool rush of her breath on my face. I put my hand on her wet stomach and it tightened under the slippery fabric of her dress, but she didn’t open her eyes. I leaned in and pressed my mouth, ever concealing the broken tooth, against hers. But I’m no fool. It was Bloodroot Mountain she tasted when I kissed her lips. I might as well not even have been there. I knew it then and I know it now. I never tried to kiss her again, but I’m glad I took my chance when I saw it.

Myra drove Mark out of his head, the same as she did me. He tried to kiss her a million times when we were teenagers. She always laughed and wriggled away as if he was playing with her, but I knew it was for real. I saw how his smile dissolved and his eyes flamed up. In high school when we went to the movies he would try to touch her in the dark, his hand sliding onto her ribs and moving up toward her breast. She would bend back his fingers until he cried out and the people behind us fussed at him to be quiet. He’d try to pretend that he wasn’t mad, walking through the lighted lobby to the parking lot where Daddy’s old truck was waiting for us, but I knew what his anger looked like.

Mark hated me when he discovered how Myra sought me out. He caught us one day coming back from a walk. He was home early from a fishing trip because nothing was biting. He watched us as he took his pole and tackle out of the truck bed to put in the smokehouse. Myra waved but he didn’t raise his hand in return. I walked her down to the road and when I came back he was sitting on the porch steps blocking my way.

“She won’t ever have you,” he said, his eyes reminding me of that crazy boy who broke my mouth with a rock when I was seven. “Ugly old snaggletooth thing.”

I climbed up the porch steps and he let me pass. I knew he was right. I couldn’t put into words why I’d never have Myra. It had nothing to do with how I looked. It was something else I couldn’t explain. I wanted to tell Mark that I love Myra’s wildness and hate it at the same time. I’m jealous because I can’t be it, and want it because I can’t have it. The only way to love Myra is from a distance, the same way Daddy loves Wild Rose.

BYRDIE

Pap lived to be a good age, but it still liked to killed me when he died. He never did get sick or feeble. He worked right up until the end, when that tractor he’d had ever since we moved to Piney Grove turned over on him. The doctor said there wasn’t nothing to do but wait for him to die. Thank goodness me and Macon got to the cabin before he passed on. The front room was packed full of people from the community he’d helped down through the years and it touched my heart to see how many had loved him. They parted to let me through and the first thing I seen was Mammy kneeling at his side. When she looked up at me her eyes was like holes and I had to turn my face. I stood at the end of the bed and took hold of Pap’s foot sticking out from under the quilt. I rubbed it through his old sock, feeling the hard corns and thick toenails he’d always pared with a knife. His face was so white it nearly blended in with the pillow. All of us waited, not speaking, for him to go. When he finally breathed his last, the breath went straight up. I seen it with my own eyes, a glow that rose and evaporated against the ceiling like steam. I held on tight to Pap’s sock foot, tears running down my face. Then I closed my eyes and prayed to the Lord that he wasn’t the only one of his kind.

Читать дальше