He has been living alone for years when Addie shows up in the late spring of 2008. He is thrilled for company, if only to have someone to cook for. He takes out his vegetarian recipes — he has a folder assembled especially for Addie’s visits. Breakfast pancakes with bourbon and vanilla and nutmeg. Lentil loaf. Carrot soup. Spanakopita. He wishes she could stay long enough to try them all.

On her last night, he makes portobello burgers and a pitcher of his famous blue margaritas. It’s a cool night, so quiet you can almost hear the moon lighting the sky. A waxing gibbous moon. They’re wearing sweatshirts, sitting by the grill.

“I need to tell you something,” Addie says. Her voice is hushed, serious.

“What’s wrong?” he says. “Is it Claree?”

“Nothing’s wrong. This is something I should have told you a long time ago. I’m telling you now because — well, just in case. I wanted you to hear it from me first.” She sips her margarita, sets the glass down. “I have a child, Sam. Had him, and gave him up. He’s grown now. He turned eighteen in September.”

“A child?”

“Yeah.”

“Born—”

“Right before you moved out here.”

“But—” Sam has a strange urge to consult a calendar. He glances at his iridescent wristwatch — nine forty-four. Time means nothing.

A child.

There has to be a right thing to say. He wishes he could think of it.

He has no memory, not even a hint of a memory, of Addie expecting a child. How could she have gone through an entire pregnancy, had a baby and given him up without her family ever suspecting?

How could anyone be so alone for so long?

But he knows the answer to that question.

“Have you told Claree?”

“No. Not yet. Maybe not ever.”

“A boy. A nephew.”

“Yeah.” She smiles, her face reflecting moonlight. “Congratulations. You’re an uncle, Sam.”

Making him sound important. Big and important as a country.

What makes Addie feel rich is, of all things, the doorbell. Not one of those lit-up plastic buttons that chimes or buzzes when you press it; she and William have a real bell forged from steel, its clapper a small steel ball. A simple, beautiful thing, weighty and substantial, like the door itself, which is solid oak. First-time visitors don’t always understand the pull for the bell. They hesitate, tug timidly at first, and the bell responds with a gentle tinkle that could just as easily be one of the wind chimes catching a ruffle of breeze, or a glass of iced tea clinking on a neighbor’s porch. Addie is attuned to all these sounds. If there’s a person at the door, the bell will ring a second time; the visitor will pull harder, too hard usually, making a bright metallic clang, loud as a window breaking.

This will set off the birds — two green-wing singing finches who live in a cage that occupies an entire wall of the dining room. They answer every sound with one of their own. Certain loud sounds — the bell when it’s pulled too hard, sirens, the vacuum cleaner, the coffee grinder — can send them into a frenzied chorus. When Addie plays records (she still has a turntable; she and William can’t part with their record collections), the birds sing along, trilling and turning their heads.

The doorbell was made by an elderly blacksmith in the Village of Yesteryear at the State Fair. Addie and William go every fall. They marvel at the bloated pumpkins and miraculously decorated cakes. They sit on bleachers in barns that smell of shit and sawdust and watch the measuring and judging of farm animals. They amble through the midway, whacking moles, pitching coins, every now and then winning some misshapen stuffed animal that they give away to a grateful stranger. They watch children on rides — wide-eyed, open-mouthed little ones spinning around and around in teacups, teenagers screaming as the Scrambler slings them and the Zipper flips them upside down.

On a clear day, Addie can sometimes coax William onto the Ferris wheel. She holds his hand. She loves his knobby, stained knuckles. She loves him for riding with her even though he’s afraid of heights (a mural painter who spends his days on scaffolding!). She loves knowing that she will love him all her life.

It’s a rich life. Richer than she thought possible.

Still, there’s something, someone, missing. There’s a hole in her that, on dark days, she worries she could cave into.

“Everybody has holes,” William says.

“I’m the holeyest,” she says. “I am the holey of holeys.”

“Yes, you are,” he says, and bows. His hair is thinning at the crown; she can see a tiny circle of bare scalp, pink and smooth. It makes her love him even more. If only that love were enough.

September 2010, a Saturday evening at the cusp of fall. The dogwood leaves are burning; the light is changing, the sun slanting at a sharper angle. The air is dry. Soggy summer is over. Soon the nights will be crisp, the stars brilliant. Whatever is ripe will be harvested or lost.

Addie loves and dreads this time of year — the dying beauty of the trees, the way the world begins its slow surrender to winter. September is the anniversary of her own surrender.

Tonight she is home early, cooking dinner — a curry, William’s favorite, with cauliflower and chickpeas. A giant stew, enough to feed them until they are sick of curry. The rice is in the cooker. She pours herself a glass of Riesling. The finches are quiet.

Outside, there is a faint tinkling. Wind chimes or doorbell? She isn’t expecting company. She waits. The sound comes again — not tentative this time. A clean, clear slice of sound, announcing someone. The exact sound the old blacksmith must have heard in his mind’s ear as he was working.

The finches flutter and chirp. Who-can-it be be be?

“Hold your tiny horses,” she tells them.

As always when she hears the bell, she moves with a deliberate, practiced calm. She sets down her wineglass, turns the curry to a low simmer, walks through the house to the front door— I have hopes but no expectations —and opens it.

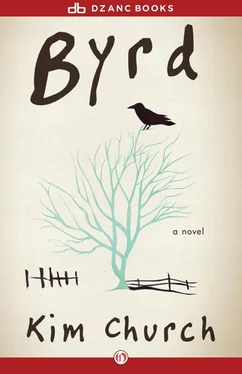

Emma Patterson, you are my dream agent. Thanks for your belief, intelligence, enthusiasm, and friendship. Guy Intoci, I could not have made up a more perfect editor. Dan Wickett, Steven Gillis, Steven Seighman, and everyone at Dzanc Books, thanks for your vision and commitment. Caitlin Hamilton Summie, thanks for your grace in helping to usher this book into the world.

For their generous support, I thank the North Carolina Arts Council, Vermont Studio Center, the Weymouth Center for the Arts and Humanities, and — my home away from home — the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, where much of this book was written.

Thanks to my mother, Martha Church, who taught me to love books, and to my late father, Max Church, from whom I inherited the habit of storytelling. Thanks to my brother and sister, Andy Church and Marty Hargrave; my sister-in-law and brother-in-law, Joni Walser and Wendell Hargrave; and my niece, Morgan Hargrave, for their unfailing love and help. To Marty, particular thanks for our discussions about childbirth.

Thanks to my high school English teacher and champion, the late Mildred Ann Raper, who opened the world to me. Thanks to Laurel Goldman for pressing me to write this novel, and to the brilliant teachers who guided me: Patricia Henley, Angela Davis-Gardner, and Jill McCorkle.

Thanks to Joyce Allen, Paula Blackwell, Mia Bray, Nora Gaskin, Nell Joslin, Nancy Peacock, and Pat Walker, whose critiques were invaluable. Thanks also to Laura Herbst and Ruth Moose for inspiration and encouragement.

Thanks to my comrades Elizabeth Kuniholm, Henry Temple, Melissa Hill, Wade Smith, and Robert Zaytoun for making it possible for me to balance my writing practice with my law practice.

Читать дальше