“You son of a bitch,” Billy said. “Are you all right?”

“Blllgggggggghhh,” Daddy said, gasping.

“Then get your ass up.”

Billy rolled him off his lap, stood up and pulled the drunken Daddy to his feet. Customers from Martha’s stood behind the two men, along with half a dozen passersby Billy leaned Daddy against the wall of the Railroad YMCA and Martha blotted his face with a wet towel, revealing a split forehead and a badly scraped nose, cheek, and chin. A prowl car arrived and two patrolmen helped Daddy into the back seat.

“Where’ll you take him?” Martin asked.

“Home. He does this regular,” one policeman said.

“You should have him looked at up at the emergency room. He might have aspirated. Inhaled some vomit.”

“Nngggggnnnhhh,” said Daddy Big.

The policeman frowned at Martin and got behind the wheel.

“He don’t have any teeth,” Billy said. Billy found the teeth on the edge of the curb, where a dog was licking the vomit. Billy reached in through the car window and put the teeth in Daddy Big’s shirt pocket. As the crowd moved back toward Martha’s, Martin saw another car pull up behind the police car, Poop Powell at the wheel.

“Hey, Phelan,” Poop called, and both Billy and Martin then saw Bindy McCall in the front seat alongside Poop. Martin parted Billy gently on the shoulder.

“You do lead a full life, Billy,” he said.

Martin sat in Martha’s window looking at Billy standing in the middle of Broadway, his back to traffic, talking into Bindy’s window. The neon sign, which spelled Martha’s name backward, gave off a humming, crackling sound, flaming gas contained, controlled. Martin drank his beer and considered the combustibility of men. Billy on fire going through the emotions of whoring for Bindy when he understood nothing about how it was done. It was not done out of need. It rose out of the talent for assuming the position before whoremongers. Billy lacked such talent. He was so innocent of whoring he could worry over lead slugs.

Slopie played “Lullaby of Broadway,” a seductive tune. Slopie was now playing in a world never meant to be, a world he couldn’t have imagined when he had both his legs and Bessie on his arm. Yet, he’d arrived here in Martha’s, where Billy and Martin had also arrived. The music brought back Gold Diggers of some year gone. Winnie Shaw singing and dancing the “Lullaby.” Come and dance, said the hoofers, cajoling her, and she danced with them through all those early mornings. Broadway Baby couldn’t sleep till break of dawn, and so she danced, but fled them finally. Please let me rest, she pleaded from her balcony refuge. Dick Powell kissed her through the balcony door, all the hoofers pleading, beckoning. Dance with us, Baby. And they pushed open the door. She backed away from them, back, back, and ooooh, over the railing she went. There goes Broadway Baby, falling, poor Baby, falling, falling, and gone. Good night, Baby.

Spud, the paper boy, came into Martha’s with a stack of Times-Unions under his right arm, glasses sliding down his nose, cap on, his car running outside behind Bindy’s, with doors open, hundreds more papers on the back seat.

“Paper,” Martin said. He gave Spud the nickel and turned to the classifieds, found the second code ad. Footers O’Brien was the top name, then Benny Goldberg, who wrote a big numbers book in Albany and whose brother was shot in his Schenectady roadhouse for having five jacks in a house deck. Martin lost patience translating the names in the dim light and turned to the front page. No story on Charlie Boy, but the Vatican was probing a new sale of indulgences in the U.S. And across the top a promotion headline screamed: “Coming Sunday in the Times-Union: How and Why We Piss.”

Billy went straight to the men’s room when he came back into Martha’s and washed off Daddy Big’s stink. Then he ordered a double scotch and sat down.

“So I told him about Newark,” he said.

“You did? Was he pleased?”

“He wanted more, but I told him straight. I can’t do this no more, Bin. I ain’t cut out to be a squealer.”

“Did he accept that?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Why don’t you think so?”

“Because he says to me, All right, hotshot, you’re all by yourself, and he rolls up the window.”

Martin, ducking his head, entered the city room at pristine morning. Across the freshly oiled floor, free now from the sea of used paper, shinbone high, that would cover it nine or ten hours hence, he walked softly, playing the intruder, hoping to catch a rat in action. The room was empty except for the clacking, which never deterred the Times-Union’s rats. It was their lullaby They got to be a size, came along a pipe from out back, and ran over the heads of the working stiffs. Benson Hunt, the rewrite man, the star, moved his desk back two feet and never took off his hat again after a three-pounder lost its footing on the pipe and tumbled into his lap. Benson screamed and tipped himself over, breaking a pint of gin in his coat. Martin had no such worries, for no pipes traversed the space over his desk, and he never packed gin. But he too wore his hat to keep his scalp free of the fine rain of lead filings that filtered through the porous ceiling from the composing room overhead.

Martin paused at the sports desk to read a final edition with the story on the blackout. Some sort of sabotage, perhaps, went one theory; though the power company and the police had no culprits. The darkness blacked out, through most of Albany County, the speech by Thomas E. Dewey, aaaahhh, largely an attack on the McCall machine. Sublime. The speech was reported separately. Political monopoly in Albany. Vicious mess of corruption in the shadow of the Capitol. Vice not fit to discuss on the radio. Politics for profit. Packed grand juries. Tax assessments used to punish enemies. Vote fraud rampant. The arrest only today of several men, one for registering twenty-one times.

Martin clicked on the drop light over his own desk and prepared to write a column for the Sunday paper, his first since the kidnapping. In the days since Charlie Boy had been taken, Martin stayed busy chronicling the event as he came to know it, for use when the story finally did break. He had filled his regular space in the paper with extra columns he kept in overset for just such distracted times.

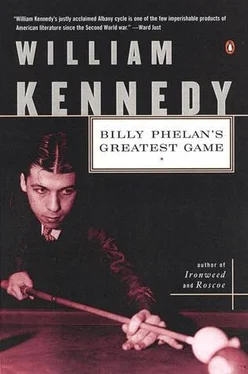

Now he wrote about Billy’s two-ninety-nine game and about Scotty dropping dead. Without malice toward Scotty, he discussed the hex, and Billy’s response to it. He viewed Billy as a strong man, indifferent to luck, a gamester who accepted the rules and played by them, but who also played above them. He wrote of Billy’s disdain of money and viewed Billy as a healthy man without need for artifice or mysticism, a serious fellow who put play in its proper place: an adjunct to breathing and eating.

By comparison, Martin wrote, I find myself an embarrassed ecclesiarch, a foolish believer in luck, fate, magicians, and divine animals. It would serve me right if I died and went to heaven and found out it was a storefront run by Hungarian palm readers. In the meantime, he concluded, I aspire to the condition of Billy Phelan, and will try to be done mollycoddling my personal spooks.

It took him half an hour to write the column. He put it in the overnight folder in a drawer of the city desk, ready for noontime scrutiny by Matt Viglucci, the city editor.

In his mailbox, he found a letter on Ten Eyck Hotel stationery, delivered by hand. Dearest Martin, I missed you at the theater. Do come and call. We have so much to talk about and I have a “gift” for you. Yours always, Melissa.

A gift, oh yes. Another ticket to lotus land? Or was there mystery lurking in those quotation marks? What son eats the body of his father in the womb of his mother? The priest, of course, devouring the host in the Holy Church. But what son is it that eats the body of his father’s sin in the womb of his father’s mistress? Suggested answer: the plenary self-indulger.

Читать дальше